The state has long taken an interest in regulating publications and art that it viewed as obscene, trying to ‘protect’ citizens and control vice. The National Archives records give an insight into the associated legislation and policing of this, as well as the networks that facilitated the production and circulating of these materials.

A post war moral panic meant this was particularly heightened in the 1920s and 30s. In this blog, collaborative doctoral student Jessica Gregory shares her latest research into a case from 1930s London, using Metropolitan Police records to trace this moment through the archives. Jessica’s emerging PhD research focuses on illicit advertisements in the early 20th century.

– Vicky Iglikowski-Broad, Principal Records Specialist in Diverse Histories, The National Archives

On 23 August 1934, the Metropolitan Police burst into two premises on Buckingham Palace Road, London, armed with a warrant to seize books under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857. The establishments at number 12 and 16 were two book businesses: the publishers, The Fortune Press and the booksellers, Sequana Ltd. The police had good reason to believe that the books in these premises would be deemed obscene because of their sexual content. Selling such works was illegal at the time of the raid because of the belief that a wide readership of such books would degrade public morals.

The police, in their role of enforcers of the Obscene Publications Act, could apply for court granted permission to seize and destroy sexually explicit books.[ref]For an overview of the Obscene Publications Act 1857 and other anti-indecency legislation see, ‘Obscenity : an account of censorship laws and their enforcement in England and Wales’ by Geoffrey Robertson (1979)[/ref] Such books, police believed, were being published by The Fortune Press and supplied to a Sequana Ltd bookshop nearby. However, the process of seizing such books could cause public controversy. The Metropolitan Police file – MEPO 3/932 – which records the raid shows how one event could cause outcry from some unexpected places.

The books seized

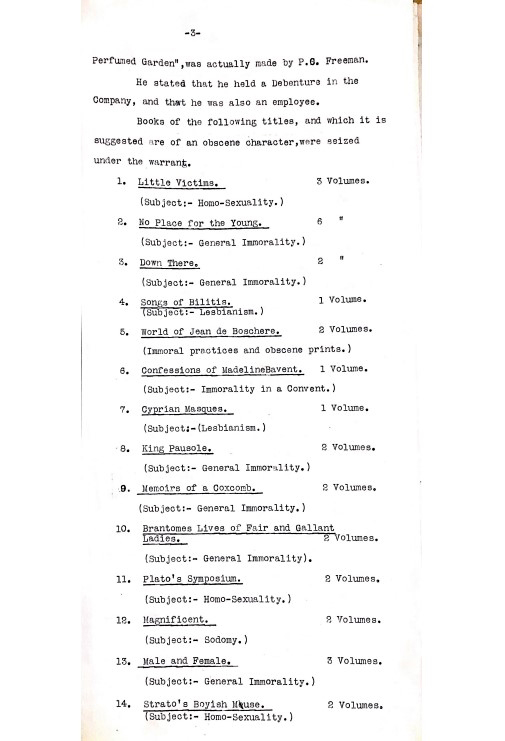

Police action under the Obscene Publications Act would mean that officers seizing books had to make decisions on what to confiscate immediately and often scoped up all available stock. Titles were confiscated from both establishments under a police warrant. A list of the books confiscated (pictured) on the day from Sequana’s shop at 16 Buckingham Palace Road illustrates some of the variety in titles seized.

As well as the various titles of general erotica, recent editions of Plato’s Symposium were also confiscated because of its valuing of homosexual relationships. This is one of a few noteworthy texts taken by the police that day, including the long form poem Don Leon – at this time attributed to Lord Byron but today is considered unknown – and The Works of Rabelais. Byron’s poem was confiscated because of its celebration of homosexual love, whereas, The Works of Rabelais, were translated satires from the 15th century full of grotesque bodily imagery that was identified as constituting general obscenity.

These texts and others were shifted through and reviewed before a court date that would determine the fate of books. Most were considered sufficiently obscene enough to have them condemned to destruction, but with a classic text such as Plato’s Symposium, action was only taken against the copies which contained modern pictures plates. It is these pictures that were identified as obscene by the police officers during the raid.

Anti-British propaganda

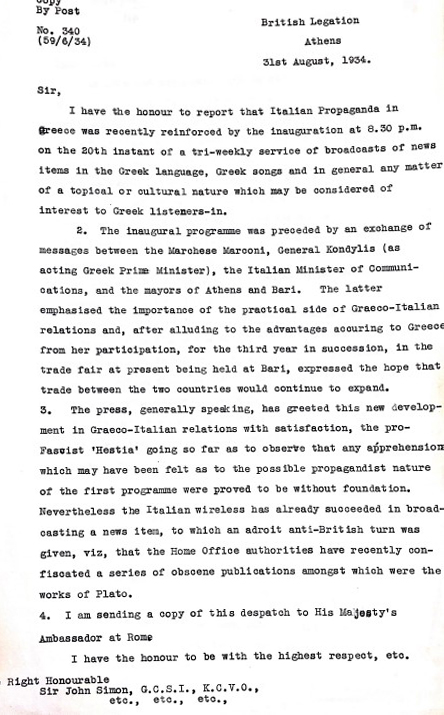

However, police action in confiscating and destroying these editions did not go unnoticed. The Home Office received a letter from the British diplomatic minister in Athens describing how the raid in London was being reported in Greece.

As this letter was read in 1934, Mussolini’s National Fascist Party had a strategic interest in exerting its influence over Greece. In 1923 Italy had directed military action in Corfu after the murder of an Italian general in Greek territory and this action had effectively led to the occupation of Corfu. Without the guarantee of its own security, the Greek government had signed a treaty of friendship with Italy in 1928. Mussolini had since maintained a continued interest in the Balkans as part of his vision of the expansion of Italian influence in the region. This attempt at influence in the region might explain Italy’s use of propaganda across Greece as explained by British officials in Greece:

‘I have the honour to report Italian propaganda in Greece was recently reinforced by the inauguration at 8.30 p.m. on the 20th instant of a tri-weekly service of broadcasts of news items in the Greek language, Greek songs and in general any matter of a topical or cultural nature which may be considered of interest to Greek listeners-in.’

British Legation, Athens, 31 August 1934

These propagandist broadcasts aimed to build on Italo-Greco relations and alienate them from the British. The Fortune Press raid made for useful anti-British propaganda to spread in Greece:

‘The Italian wireless has already succeeded in broadcasting a news item, to which an adroit anti-British turn was given, viz, that the Home Office authorities have recently confiscated a series of obscene publications amongst which were the works of Plato.’

British Legation, Athens, 31 August 1934

The Home Office identified very little they could do in response to the story about the confiscations in the anti-British propaganda. They excused the inclusion of classic books because of the inability of police officers to separate the obscene and the accepted when raiding bookshops. In essence: such mistakes were an unfortunate hazard of ensuring the safety of the public from such indecent books.

Lord Alfred Douglas

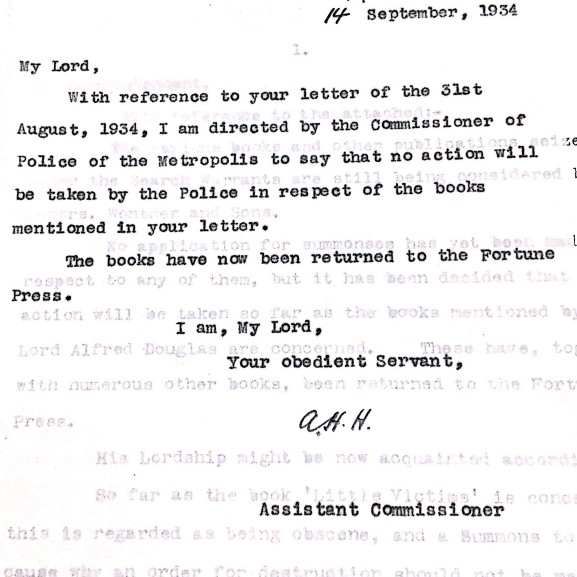

Unfortunately, for authorities, controversies over this raid did not end there. The director of the Fortune Press, Mr Caton, sent out correspondence immediately after the raid seeking out notable authors that might react against the raid. One of the letters that he sent out was to Lord Alfred Douglas.

Lord Douglas, also known as Bosie, was not immune to controversy himself. He was Oscar Wilde’s lover at the time of Wilde’s trial in 1895 when Douglas’s poetry was held up as evidence of gross indecency between the two.

In 1918, his sympathies for those accused of ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ had seemingly diminished.[ref]‘The love that dare not speak its name’ is quoted from Douglas’s poem, ‘’Two Loves’’ published in 1892 in the Chameleon magazine. The line is widely considered a euphemism for homosexual love. Two Loves by Lord Alfred Douglas – Poems | Academy of American Poets[/ref] In 1918, he gave evidence against the dancer Maud Allan who was defending herself from published allegations that she was a lesbian. By 1934, the time of Fortune Press book raid, Douglas was furious to be associated with those writing erotica or selling indecent goods. He wrote to the Metropolitan Police saying that his Collected Satires, which had been confiscated in the raid, were in fact, a volume of poems that attacked the prevalence of various vices and abuses in society. Douglas then went on to outline his credentials as ‘England’s greatest living poet’ before turning on the proprietor of the bookshop Mr Caton, explaining that no one has a kind word to say about him.[ref]Quote from a letter to Commissioner of Metropolitan Police from Lord Alfred Douglas, dated 31st August 1934. Catalogue Ref: MEPO 3/932.[/ref]

Douglas’s letter of complaint seems to have been taken seriously. After writing one more letter that threatened to get his lawyers involved, the police dropped Douglas’s two titles from the books being prosecuted. Douglas’s influence and profile appear to have been enough free his titles from further action, but most of the books seized in this case would not be so lucky and would find themselves destroyed after the judge found them to be obscene.

The controversies that police bookshop raids could provoke were of growing concern to the Home Office in the nineteen-thirties. After the trial of the lesbian-themed novel, The Well of Loneliness in 1928, the government was increasingly weary of the media and public storm that anti-obscenity action could provoke. There was much media debate on the limits of freedom of speech under such laws and where the line should be drawn between pornography and art. The attentions of the Italian Fascists and celebrities such as Douglas were not appreciated by authorities trying to enforce an increasingly controversial law.

Jessica Gregory is an AHRC-funded PhD student collaborating with The National Archives and The University of Kent. Her work examines evidence of censorship of sexual print in government records.

We support doctoral students across a range of disciplines by providing supervision and access to research facilities.

‘Don Leon’is definitely not actually by Lord Byron since the text mentions incidents which took place after his death. The title obviously alludes to ‘Don Juan’, but it is worth noting that the first two Cantos of Byron’s ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’, originally only intended for private circulation, did at first contain much more gay content which the poet himself edited out so that it could have public release. Polidori’s (prose) ‘Vampyre’ was also often attributed to Byron which obviously helped with sales.

This is fascinating. I knew of some of the the bare bones but not the detail sournding the story. Thank you very much. Most interesting.