![1622. Engraving showing the burning of the major German cities taken by Prince Christian, Duke of Brunswick (catalogue reference EXT 9/41 [extracted from SP 9/201]).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144935/TYW-1-Christ.jpg)

1622. Engraving showing the burning of the major German cities taken by Prince Christian, Duke of Brunswick (catalogue reference EXT 9/41 [extracted from SP 9/201]).

As part of The National Archives’ ongoing Reformation programme, I set out to explore how a domestic revolt in Bohemia led to a continental-wide war by the 1630s, and how it impinged on the Stuart kingdoms. I’ve used archival material from the ‘State Papers Foreign’ series. This was originally gathered by the Stuart Crown’s agents, and dispatched to British envoys – such as Sir Dudley Carleton at The Hague, and Viscount Scudamore in Paris, for example.

The Thirty Years War has been regarded by historians as the first ‘total war’ in terms of complete and absolute destruction. The conflict devastated whole regions, with famine and disease resulting in a high mortality of the populations of the Central European states. The war would also bankrupt most of the combatant powers.

The losses were great and varied regionally. The largely Catholic Württemberg (in south-western Germany) lost three-quarters of its population during the war, while in the (north-eastern) territory of Calvinist Brandenburg, the losses amounted to around half. Much of this destruction of civilian lives and property was caused by the plundering of mercenary soldiers. Although the sack of Magdeburg by the Imperialists under Marshal Tilly in 1631[ref]This attempt by Catholic League forces to retain the loyalty of Saxony by terror led directly to an alliance between its elector, Johann Georg, and Sweden. J.Polišenský, ‘War and Society in Europe 1618-1648’ (Cambridge 1978), 141.[/ref] is considered to be the worst massacre of the war, Swedish armies alone may have destroyed one third of all German towns.

While the rights of the Bohemian Estates[ref]Whereby orthodox Catholics co-existed alongside Lutherans, Calvinists, and Hussite Utraquists (who believed in the Eucharist communion of both kinds). P. Wilson, ‘Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of The Thirty Years War’ (London, 2009), 59.[/ref] had been confirmed by the ‘Letter of Majesty’ of 1609[ref]The Emperor Rudolph II had reluctantly granted concessions to both Protestants and Catholics in the Estates of Bohemia as a bulwark against the Ottoman Turks. P. Wilson, ‘Who Won The Thirty Years War?’ (History Today, Aug 2009), 15.[/ref], the ageing Habsburg Emperor Mathias (who had ascended the throne in 1612), began to curtail Bohemian freedoms and close Protestant chapels. He nominated the hard-line, Jesuit-educated Ferdinand of Styria to be his successor. These actions led to the ‘Defenestration of Prague’ (23 May 1618) when the Imperial regents Slavata and Martinic – having been found guilty of violating Bohemia’s religious guarantees – were famously flung from an upper window of the Hrachy Castle. A minority of the Protestant nobility, led by Count Thurn, rose up under the pretext of defending their liberties. They duly invited the Calvinist Frederick V of the Palatinate to be their ruler, an invitation Frederick very unwisely – and, above all, quite illegally – accepted.

![1619. Poem celebrating the birth ‘Att Christmas’ of Prince Rupert of the Rhine to Elizabeth of Bohemia at Prague [Hrachy Castle] (catalogue reference SP 9/20, f.2).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144936/TYW-2-Poem-Big.jpg)

1619. Poem celebrating the birth ‘Att Christmas’ of Prince Rupert of the Rhine to Elizabeth of Bohemia at Prague [Hrachy Castle] (catalogue reference SP 9/20, f.2).

![1620. Letter [sent from Holland] reporting on the Habsburg victory over the rebel Bohemian [Estates] army at the Battle of the White Mountain (Catalogue reference SP 84/98, f.88).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144937/TYW-3-White-Mountain-1.jpg)

1620. Letter [sent from Holland] reporting on the Habsburg victory over the rebel Bohemian [Estates] army at the Battle of the White Mountain (Catalogue reference SP 84/98, f.88).

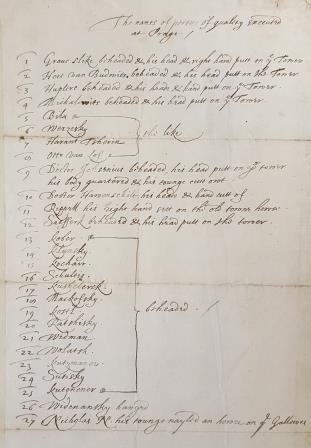

1621. Persons of quality condemned [by the ‘Prague Blood Court’], and the means of their execution in the Old Town Square (catalogue reference SP 80/238).

Throughout the 1620s the House of Austria was victorious. Allied with her close relative Spain, this great power block seemed unstoppable. The ‘Palatinate cause’ was, at best, only half-heartedly supported by foreign states, although the Dutch United Provinces would consistently support the overall Protestant cause throughout the period. James I of England was stirred enough to send over a token expeditionary force in 1622 to the Rhineland under Sir Horace Vere, in support of his daughter (the ‘Winter Queen’) Elizabeth, Electress Palatine[ref]Born in Fifeshire in 1596 to (the then) James VI of Scotland. Christian of Brunswick, as champion of the Palatinate cause, would declare his ‘chivalric love’ for her.[/ref].

A number of leading Civil War commanders such as the Earl of Essex (the later parliamentary Lord General)[ref]Whose relative (from the Irish line) Captain Walter Devereux of Ballymagir, at the behest of the emperor, would be implicated in the murder of the great warlord and military entrepreneur Albrecht von Wallenstein, at the fortress of Eger in 1634. R. Manning, ‘An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585-1702’, 2006), 90.[/ref] and Ralph Hopton (the King’s generalissimo in the west)[ref]Hopton (whose own religious convictions would border on presbyterianism) as a member of Elizabeth’s lifeguard had escorted the Electress and the infant Prince Rupert to safety after the Battle of the White Mountain.[/ref] would gain valuable military experience on this German campaign. Much criticism was levelled at King Charles I for not supporting the Protestant cause enough.[ref]Charles did agree to send naval expeditions (however disastrous) to Cadiz in 1625, and to the Isle of Rhé in support of the Huguenots of La Rochelle in 1627. However, in the next decade, during the period of his personal rule, Charles did permit large-scale recruitment within his three kingdoms of men for foreign armies.[/ref] Offering the Spanish treasure fleet safe passage through the Channel; the Dutch would be accused of flagrant violation of English neutrality after its destruction at the Battle of the Downs in 1639.

![1631. Warrant from Charles I authorising the recruitment for Lord Reay [Donald Mackay's] Regiment in the service of the King of Sweden (catalogue reference SP 16/198, f.44.)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144938/TYW-5-Reay-big.jpg)

1631. Warrant from Charles I authorising the recruitment for Lord Reay [Donald Mackay’s] Regiment in the service of the King of Sweden (catalogue reference SP 16/198, f.44.)

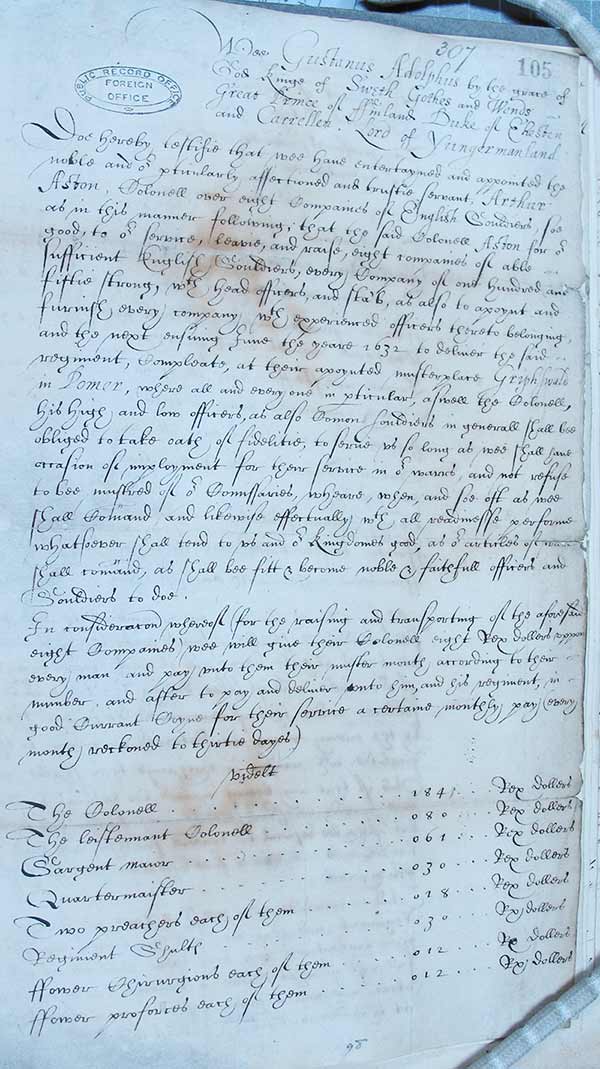

1631. Declaration by Gustavus Adolphus King of the Swedes, Goths, and Wends…’ for a regiment of 3,000 men to be raised by Colonel Arthur Aston (catalogue reference SP 95/3, f.105).

The war rapidly escalated when Gustavus Adolphus, ruler of Lutheran Sweden (to be celebrated as the ‘Lion of the North’), embarked his army on the Baltic shore in 1630.[ref]Championing Protestant liberties against the Imperial Edict of Restitution, which had attempted to reverse the religious settlement of 1555 (the Peace of Augsburg) between Charles V and the Princes of the Schmalkaldic League. In reality, Vasa Sweden could claim to be waging a defensive war. [/ref]Alarmed by the sheer scale of Imperial successes in the north after the collapse of Denmark in the field, which followed her defeat at Lütter in 1626 and the harsh Treaty of Lübeck in 1629, the Swedish king was fearful of a resurgent Poland.[ref]Whose ruler Sigismund III (as a Catholic Vasa) had a legitimate claim to the Swedish throne.[/ref]

Sweden, moreover, as a voracious military contractor, would hire troops of all religious persuasions from across Europe; like the Putney-born Catholic, Arthur Aston, for example, who had fought for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until the Truce of Altmarck in 1629.[ref]As Royalist governor of Drogheda, Aston would be killed (during the infamous storming of the town by the New Model Army) in 1649.[/ref] Scottish ‘soldiers of fortune’ were particularly sought after; both Alexander Leslie, the later Covenanter general, and Hugh Monro, who would command the Scots troops in Ulster in the 1640s, had both seen military service with the Swedes in northern Europe. Although the Kingdom of Sweden-Finland was to be ably administered by the regent Axel Oxenstierna after Gustuvas’s death at Lützen, her defeat at Nördlingen in 1634 would herald the beginning of her century-long decline as a great power.

![1631. Pass authorised by the Privy Council for Colonel Aston to go over[seas] with his wife and family to raise an English regiment for Swedish service (catalogue reference PC 2/42, f.105).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144939/TYW-7-Big-Aston-Pass.jpg)

1631. Pass authorised by the Privy Council for Colonel Aston to go over[seas] with his wife and family to raise an English regiment for Swedish service (catalogue reference PC 2/42, f.105).

![1632. An account from Paris regarding the Battle of Lutzen [Saxony] between the King of Sweden and the Imperial army (Catalogue reference SP 80/8 f.247).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144940/TYW-8-Big-Lutzen.jpg)

1632. An account from Paris regarding the Battle of Lutzen [Saxony] between the King of Sweden and the Imperial army (Catalogue reference SP 80/8 f.247).

![1634. Report (in French) from Brussels [Spanish Netherlands] of the Imperial Catholic army's victory [under the Cardinal Infante] over the Protestants at Nordlingen [Bavaria] (catalogue reference SP 121/40).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144941/TYW-9-Big-Nordlingen.jpg)

1634. Report (in French) from Brussels [Spanish Netherlands] of the Imperial Catholic army’s victory [under the Cardinal Infante] over the Protestants at Nordlingen [Bavaria] (catalogue reference SP 121/40).

The Royalist Henry Gage, who came from a prominent Surrey recusant family and would lead the Oxford Horse in the relief of Basing House in 1644, had enlisted as a gentlemen pikeman before becoming captain-commandant of the English regiment (under Sir Edward Parham) in the Spanish Netherlands. While Owen Roe O’Neil and Thomas Preston, as generals of the Irish Confederate forces during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, were both veterans of the Army of Flanders.[ref]Both had commanded the Tercio Viejo Irlandes (or ‘Old’ Irish Regiment) in the 1630’s, and had recruited men in Ireland with the permission of the English and Irish Privy Councils.[/ref]

![1640. [Secretary of State, Nicholas] Windebank to all J.P's. Warrant by His Majesty permitting the levying of 2,000 men to be transported to Flanders under Captain Thomas Edwards for the English companies in the service of the King of Spain.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144942/flanders.jpg)

1640. [Secretary of State, Nicholas] Windebank to all J.P’s. Warrant by His Majesty permitting the levying of 2,000 men to be transported to Flanders under Captain Thomas Edwards for the English companies in the service of the King of Spain. (Catalogue reference: SP 16/444, f.10)

By financing Sweden’s armies (like the forces under the independent contract commander Bernard of Saxe-Weimar), Richelieu skillfully managed to split the Habsburg alliance; and by well-placed political and military action, Catholic France would permanently be able to tip the balance of power. The decisive French victory at Rocroi in 1643 would, furthermore, bring an already decaying Spain to humiliating terms.[ref]Only in 1659 would the Peace of the Pyrenees officially end Franco-Spanish hostilities, and herald the beginnings of French hegemony in Europe.[/ref]

.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144943/rocroi.jpg)

1643. Report from Sir Dudley Carleton on the ‘great defeat given the Spaniards’ at Rocroi by the French [under the Duc d’ Enghien](Catalogue reference SP 16/497, f.160).

While the military innovations of the Swedish army in tactics and weaponry (which had improved upon the flexible Dutch system), would be increasingly adopted in the war-torn British Isles of the 1640s, the European conflict itself was finally brought to a conclusion with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which gave political equality to Calvinists.

![1648. Treaty of Peace made at Munster, Westphalia between Philip IV, King of Spain, and the States General of the Netherlands [ratified in October to end the hostilities between France, Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire] (Catalogue reference SP 113/6, f.1).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/01144941/TYW-12-Munster-Westphalia.jpg)

1648. Treaty of Peace made at Munster, Westphalia between Philip IV, King of Spain, and the States General of the Netherlands [ratified in October to end the hostilities between France, Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire] (Catalogue reference SP 113/6, f.1).

Very interesting and horrifying (to hear of so many deaths) at the same time. Great blog!.

You could have knocked me over with a feather when I saw the engraving at the beginning of this piece. I have a poor copy (bought at a flea market in Heidelberg for 4 Marks in the early ’80s) depicting towns on fire with cameos of Fernandes in one corner and Tilly in the other. Catholic victories instead of Protestant.

Despite the historically Protestant tendencies (they are now mostly indifferent or agnostic) of the people of Prague, it is the site of one of Catholicism’s most famous icons – the Infant Child of Prague which is in the church of Our Lady of Victory.

Swedes plundered the church and threw the statue behind the altar. Seven years later it was salvaged.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infant_Jesus_of_Prague

I came across this accidentally. Isn’t it great the way things can almost segue, effortlessly, into each other when starting with a particular topic? As it happens, a Czech artist friend of mine, Josef Ryzec, has just completed exhaustive research on a family tradition, that he is descended from an Irish soldier who fought in the 30 Years War. Not just any old soldier, as it turns out, but the very same Walter Devereux who delivered the final thrust to Generalissimo Wallenstein (Valdštein) on 25 February 1634 in Eger (now Cheb on the Czech German border). In his search Josef has bothered(!) the National Archives, among many other sources. Josef’s quest will be published shortly, together with the DNA results which prove conclusively his descent from the Norman/Irish knight, Walter Devereux of Balmagyr. Walter got a very bad press at the time, being regarded as a mercenary murderer, but was he not in fact a loyal servant of the Emperor who wanted rid of his treacherous general who wanted to betray the Empire to the Swedes? History students of universities in the countries involved in the war will be asked to reach a consensus in a project entitled “Has the Jury reached a verdict?”.