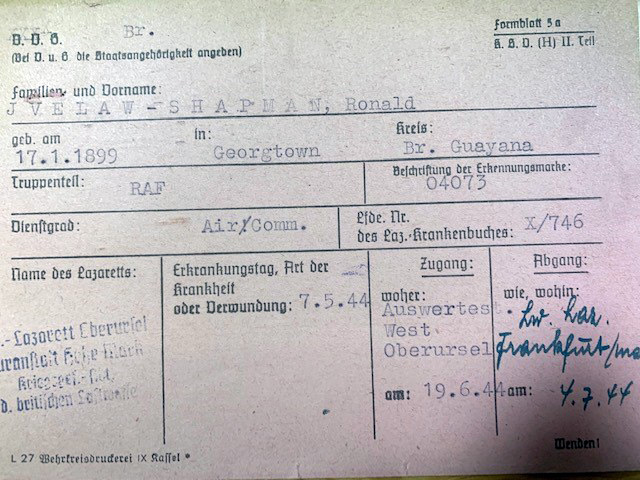

Now approaching the half-way mark in the WO 416 (Second World War British and Allied Prisoner of War record cards) project, our volunteers have recently uncovered the two ‘hospital cards’ for the late Sir Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman (WO 416/192/456). At the time of his capture in May 1944, he was an Air Commodore and the most senior Bomber Command officer ever to be captured by the Germans.

An initial search reveals that his life story would have been totally at home in the pages of the ‘Boys Own’ magazine! Born in January 1899 in Georgetown, British Guiana, his father was a merchant adventurer of Franco-Jewish extraction – his maternal grandmother being a French Creole. At the age of four he was brought to England, and at seven he was sent to the Junior School of Cheltenham College. By his own admission he never showed any real promise as a scholar and failed to reach the Upper Sixth Classical.

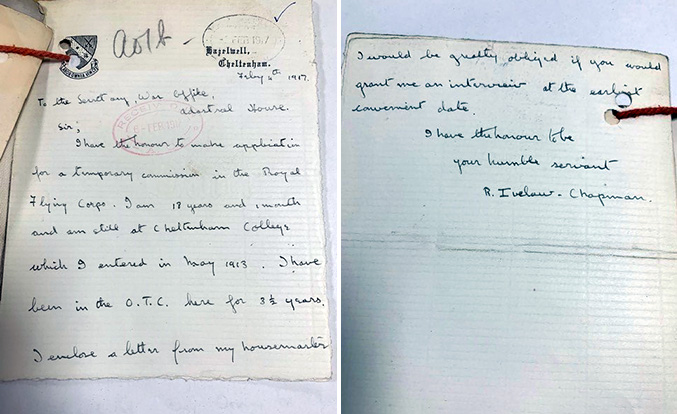

Ivelaw-Chapman’s application to join the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. Catalogue reference: WO 339/119267

While still at school and aged 17, he enlisted in Kitchener’s Army, which committed him to join on his 18th birthday. He duly left Cheltenham on the morning of his birthday and enlisted into the Royal Flying Corps that same afternoon as a 3rd Class Air Mechanic. Soon after, he became an officer cadet and on completion of his training and the award of his wings, he was posted in February 1918 to No. 10 Squadron having just turned 19.

Flying the Bristol Fighter, his task was artillery observation. He survived unscathed the last nine months of the war as a combat pilot, flying more than 500 operational hours and receiving a well-earned Distinguished Flying Cross.

Granted a regular commission in the newly formed Royal Air Force, in 1919 he was posted to No. 97 Squadron stationed in India, where he remained until 1922. His exploits in India gained him the India General Service Medal with three clasps. Returning home, his next appointment was as a test pilot with the Aircraft and Experimental Establishment at Martlesham Heath. During his five years at Martlesham he flew no fewer than 78 different types of aircraft.

In 1928 he volunteered for overseas service and was posted to No. 70 Squadron in Iraq. Now flying the Vickers Victoria troop carriers, he was based at Hinaidi in Baghdad, from where his flights took him throughout the Middle East and included piloting King Feisal on a general tour of desert posts.

In 1929 No. 70 was summoned from Baghdad to Risalpur in the North-West Frontier Province to undertake the Kabul air evacuation of the British Legation, who were beleaguered during the violent Civil War.

The flight from Baghdad to Risalpur was an epic adventure but was nothing compared to the challenge he faced flying over the mountains of the Hindu Kush to Kabul. As the peaks rose to 10,000 feet he was forced to push the Vickers Victoria to its uppermost limits.

On his second flight into Kabul he suffered dual engine failure at 12,000 feet, before making a successful forced landing on a 60-yards-long plateau high in the mountains. Both he and his co-pilot were at once surrounded by heavily armed and warlike Afghan tribesmen. Remaining for three weeks in hostile territory, he was eventually rescued by air and flown to Peshawar. His exploits in Afghanistan earned him the award of the Air Force Cross.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman in the cockpit

His career followed a more conventional pattern in the ten years leading up to World War Two. He married in 1930 and attended the RAF Staff College. He then became a member of the directing staff there, with a spell on intelligence staff work at the Air Ministry. At the commencement of the war he was on the staff of HQ Bomber Command based at High Wycombe.

In June 1940 he was appointed Station Commander, No. 4 Group Bomber Command at Linton-on-Ouse, equipped with the Whitley bomber, where one of his junior officers was Leonard Cheshire. He was tasked with flying bombing raids over Germany and Italy. There then followed in June 1941 a posting to the Air Ministry for highly secret work planning for D-Day; he held the designation of Director of Plans and then Director of Policy through to February 1944.

Eager to return to operational involvement, in February 1944 he was appointed as a Base Commander at Elsham Wolds, with three stations under his command equipped with Lancasters and Stirlings. Detecting there was a certain amount of ill feeling among his aircrews that sorties into France did not count as a full tally of operations, he sought approval to fly as a second pilot on a raid over occupied France to restore morale and this was granted. Taking off on the night of 6 May 1944 in a Lancaster, their target was the German ammunition dump at Aubigne Racan, north of Le Mans. Unfortunately the flight ended in disaster with only two of the crew surviving: Ivelaw-Chapman and the Flight Sergeant wireless operator/bomb aimer.

On the run from the Germans, and with the aid of the French Resistance, he evaded capture until 8 June, when the house in which he was hiding was surrounded by the Gestapo. During this time he was suffering from a severely dislocated shoulder, due to him failing to secure his parachute correctly when leaving his plane.

Meanwhile the Resistance had successfully contacted London to pass on the information that he was alive. On Churchill’s instruction the order was given to mount a rescue operation, but on no account was he to be allowed to fall into German hands alive in view of his knowledge of the impending D-Day operation.

Medical card for Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman for his time as POW at Dulag Luft 1 Oberursel during the Second World War. Catalogue reference: WO 416/192/456

Captured by the Gestapo, he remained under intense interrogation until 15 June, during which time they failed to persuade him to disclose the information he knew. Having convinced them that he was an RAF officer, he was finally released to a POW camp and his damaged shoulder at last received treatment. Liberated by the American forces from a camp near Nuremberg on 16 April 1945, he persuaded a US Colonel to fly him out by DC3 via Paris to England. On 19 April he completed the obligatory MI9 debriefing form (WO 208/3336/2), which details his capture and subsequent treatment as a POW.

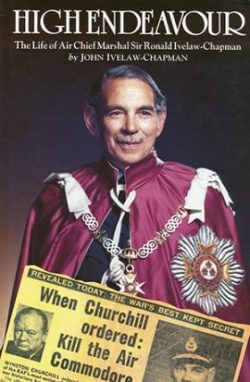

Front jacket image of High Endeavour by John Ivelaw-Chapman

Postwar he was promoted to Air Vice-Marshal and in August 1945 given command of No. 38 Group at Marks Hall in Essex. Later he became RAF Member, Defence Research Policy Staff and in 1947 he was appointed to the Directing Staff, Imperial Defence College. During 1950–51 he was seconded with the rank of Air Marshal as Commander-in-Chief, Indian Air Force, based in Delhi. During this time he had sole use of a Spitfire Mark XXI and made 58 trips away from Delhi visiting air force units throughout India.

Returning home to England in December 1951, he was suffering from an obscure tropical disease which necessitated a spell in the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in London. His final appointments were on the Air Council, firstly as Deputy Chief of the Air Staff and then as Vice-Chief of the Air Staff.

Retiring from the Royal Air Force as Air Chief Marshal in November 1953, he died of abdominal cancer in 1978.

Further reading

High Endeavour by John Ivelaw-Chapman (Leo Cooper, 1993; ISBN 0 85052 316 8)

Online biography

Fascinating story and a great showcase of the work of volunteers.

Can I suggest a slight edit?

It might be better to write ‘During this time he was suffering from a severely dislocated shoulder, due to him failing to secure his parachute correctly when leaving his plane.’ as the word ‘ejecting’ is linked to ejection seats which were not introduced in British aircraft until after the Second World War- although a few German late-war military aircraft were so equipped.

Thanks Richard – amended!

Thank you in turn Matthew – I know the criticism of the original choice of words could sound nit-picking on one level but to some people these things can mean a lot. I have made a note to read WO 208/3336/2 together with the Squadron ORB the next time I have a little spare time at Kew.

Amazing! What a character! I was aware of there being a bit of a flap when a senior officer with D-Day planning knowledge was shot down. I guess this was him. Or maybe there was more than one?

An excellent read – thank you Peter, and to the rest of the dedicated volunteers & staff overseeing the project. This work makes a hugely significant impact in opening up records like this for the wider public to benefit from. Top stuff from a top team.

This character is quite amazing and we have to respect them whatsoever the means possible. And those who fought for this country in great wars in the past cannot be appreciated enough.

I live in Aubigné-Racan quite near the old ammunition dump which was decommissioned by a German company a few years ago. The locals were amused when the company discovered an unexploded RAF bomb and had to dismantle it. Part of the land is now an Ecopark. I recently read “Into Enemy Arms” by Michael Hingston who mentions the Air Chief Marshall and the skill of the German surgeon who operated on his shoulder. By the way, Aubigné-Racan is south of Le Mans.

You state that he retired from the R.A.F in 1953 but as A.T.C Cadets in 1921 Sq. we were inspected by him in 1955.

My grandpa was on that plane to Le Mans. He never came back sadly, and left my mother without her father. I’m her son. This loss echoes down the generations, I can tell you first hand.

His name was Charles Victor Fox. It can be looked up.