This is an unfailingly accurate, if not exactly helpful, answer to the question ‘How old are you?’. It’s also the answer my mother sometimes uses as an alternative to ‘Mind your own business’ and she is not alone in that!

Ages, or supposed ages, appear in many historical records, and are of particular importance to the genealogist – or at least they would be if we could rely on them. There’s a lot of inaccuracy out there, as many of us discover very early in our research. There are all sorts of reasons for this, and they don’t all involve dishonesty. It’s virtually impossible to get through life these days without having to provide, and often prove, your date of birth; we should all have birth certificates, and many of us also have driving licences, passports and other official documents.

But if you go back only a couple of generations, things were very different. As recently as a century ago you could travel overseas without needing a passport, hardly anyone had a driving licence and there were not many situations where a person might be required to prove their age. These were mostly related to starting or leaving school, and in some cases to employment.

Going back further still, before compulsory education, there were fewer occasions still when a person might need to prove their age, although there were times when they would be required simply to state it, notably when they married, or when the census enumerator called. So we should bear in mind that when we look at historical documents for evidences of age, the information may not be accurate. Even birth, marriage and death certificates, which are admissible as evidence in courts of law, are not free of inaccuracies, for a number of reasons.

It may seem strange to the 21st century researcher, but in the past a great deal of information was taken on trust, and many people did not know exactly how old they were. Birth certificates are, on the whole, accurate, but I have seen quite a few for miracle children who were apparently baptised before they were born! This is due to parents who had a child baptised soon after birth, but were slow to register the birth; you were allowed six weeks for this, after which a fine was payable, and some parents simply adjusted the date they gave to the registrar to avoid the fine.

Ages at marriage need to be treated with caution, and not just because some people lied. The Registrar General’s ‘Suggestions for the Guidance of the Clergy’ in 1903 says:

‘The precise Age of each of the Parties at his or her last Birthday should be inserted wherever it can be ascertained; but if either of the Parties is unable or unwilling to state his or her precise age the words ‘of full age’ or ‘minor’ or the approximate age (eg “about 30”) may be recorded’

So you can see the possibilities for misunderstanding there, when someone looks at the marriage entry many decades later. I once did a straw poll on a sample of 100 marriage entries where I had independent verification of the parties’ ages, and found that 25 of the certificates contained a wrong age! Most of them were only out by a very small amount, usually where a person who was 19 or 20 claimed to be 21, this being the age when they could marry without parental consent in England and Wales. Similarly, you might see ‘21’ when someone is somewhat older, but where the vicar or his clerk just writes this for everyone who is 21 or above. And some people just lied. For the record, the biggest lie I have discovered was by a man who lopped a full 20 years off his stated age when he married a much younger woman.

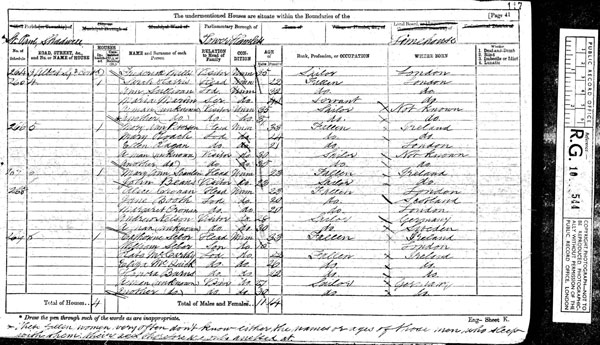

Ages in death and burial registers rely on information provided by the informant or next of kin, which may be no more than an educated guess, and much the same goes for many census returns. You might reasonably expect the head of household to know the ages of their own family, but what about guests, or lodgers, or servants? One of my favourite census pages is for Albert Square in the east end of London in 1871 where the enumerator has written:

‘ These fallen women very often don’t know either the names or the ages of those men who sleep with them, their ages can therefore only be guessed at.’

No wonder that in reference to a later census, the Registrar General wrote:

‘…that the one column in the householders’ schedule which gives he most trouble to occupiers, causes the greatest dislike to Censuses, and is most liable to the suspicion of inaccuracy when filled up, is the Age Column’ (RG 19/42)

Despite this, there came a time when these imperfect records were used to provide proof of age. When Old Age Pensions were introduced in 1908, for people over 70, claimants had to provide documentary proof of age. Very few had birth certificates, since registration was not introduced until 1837 in England and Wales, 1855 in Scotland and 1864 in Ireland. Most had baptismal certificates, or failing that, a marriage certificate was acceptable. But as a last resort, a search in the un-indexed original census books was required. The GRO was very reluctant to do this, claiming that it was difficult and time-consuming with little guarantee of success. Correspondence on the subject even contains replies to unfortunate applicants telling them that the records were not available for searching at all (RG 19/188).

Men who joined the armed forces were asked for their age or date of birth, and many of these stated ages are wrong, too. Lots of young men claimed to be older than they were to get a better rate of pay, or simply to join up at all when they were under-age. The ‘unburnt documents’ in WO 364 contain a number of records of these young boys. My great-uncle James Calderhead joined the army twice, in 1914 and 1915, each time being found out and discharged. He tried to join the Royal Marines in 1915, and finally the Royal Navy in 1916, where he served for the duration of the war. He claimed he was born in 1894, 1896, 1897 and 1898 respectively, but his actual date of birth was 15 March 1900 (not 1901 as in the document below – I’ve seen the certificate).

Discharged 'having made a mis-statement as to age on enlistment' (reference: WO 364)

How very true it all is.

I’ve come across all of these discrepancies over the last 20 years of research, however there’s one scenario which you’ve missed.

I’ve seen women listed on the 1920-28 Electoral Registers who were clearly not 30 or over as the Law stated they should be.

After the war & the effort women put into it I think many thought it was an insult not to have the right to vote & who could blame them.

This one really had me tied up. It was expressed as ‘ I’m as old as my gums but a year younger than my teeth’ It could only take a Yorkshire lass to say that. Being a Southerner, I sometimes wish I I’d been born up North.