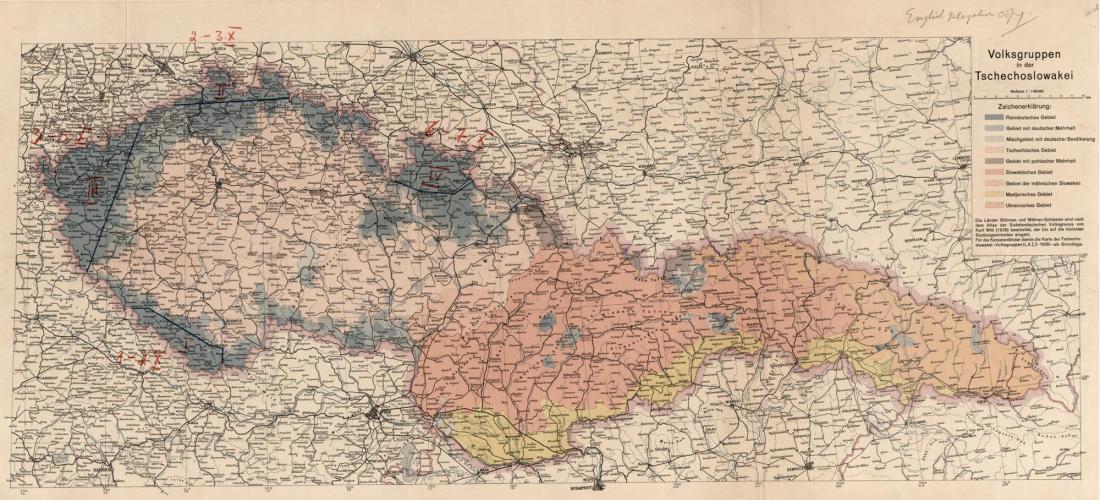

‘Volksgruppen in der Tschechoslowakei’ (‘Ethnic groups in Czechoslovakia’): a German-language map of the country. Catalogue reference: FO 925/20108.

During 1938, political tensions in Europe heightened as the major powers continued to rearm. Adolf Hitler, engaged upon a policy of territorial expansion, had already completed the Anschluss (incorporation of Austria) in March. Hitler next made demands upon Czechoslovakia, including the annexation of Sudetenland, a part of the country dominated by ethnic Germans. Within Czechoslovakia, these demands were supported by the Sudeten German Party, led by Konrad Heinlein.

As the map at the top of this post [ref] 1. FO 925/20108. [/ref] shows, Czechoslovakia was a multi-ethnic country. The colouring on the map reflects the distribution of national or linguistic groups. Areas with a Czech majority are coloured beige, Slovak areas are pink and German areas blue. Yellow, orange and mauve indicate predominantly Hungarian, Ukrainian and Polish areas respectively.

The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, sought to avoid a war with Germany through a policy of appeasement. In mid-September, the British and French governments demanded of the Czechoslovak President, Edvard Beneš, that those parts of Czechoslovakia in which ethnic Germans made up more than half of the population should be ceded to Germany. Politically isolated, Beneš was forced to capitulate. Hitler then pressed further demands, including the breakup of Czechoslovakia and the immediate annexation of the whole of Sudetenland.

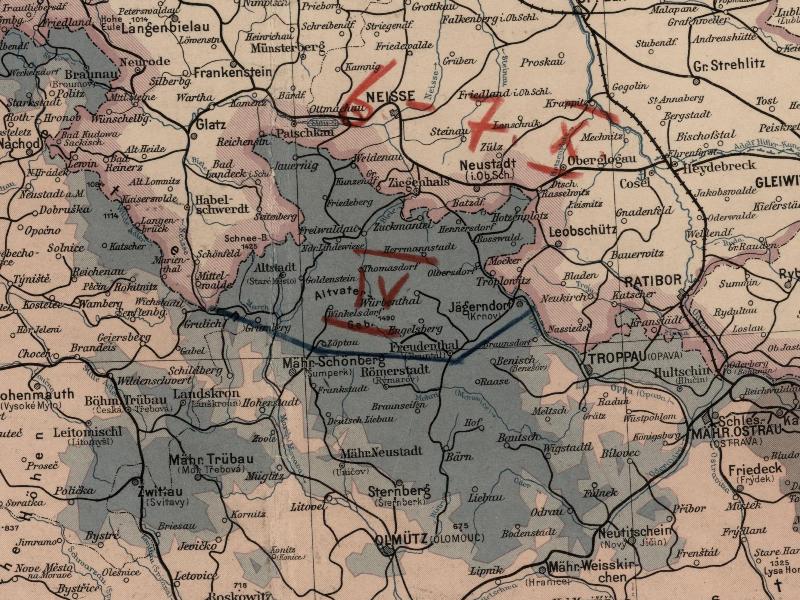

Hitler’s plan was for German troops to enter this portion of Sudetenland between 6 and 7 October 1938.

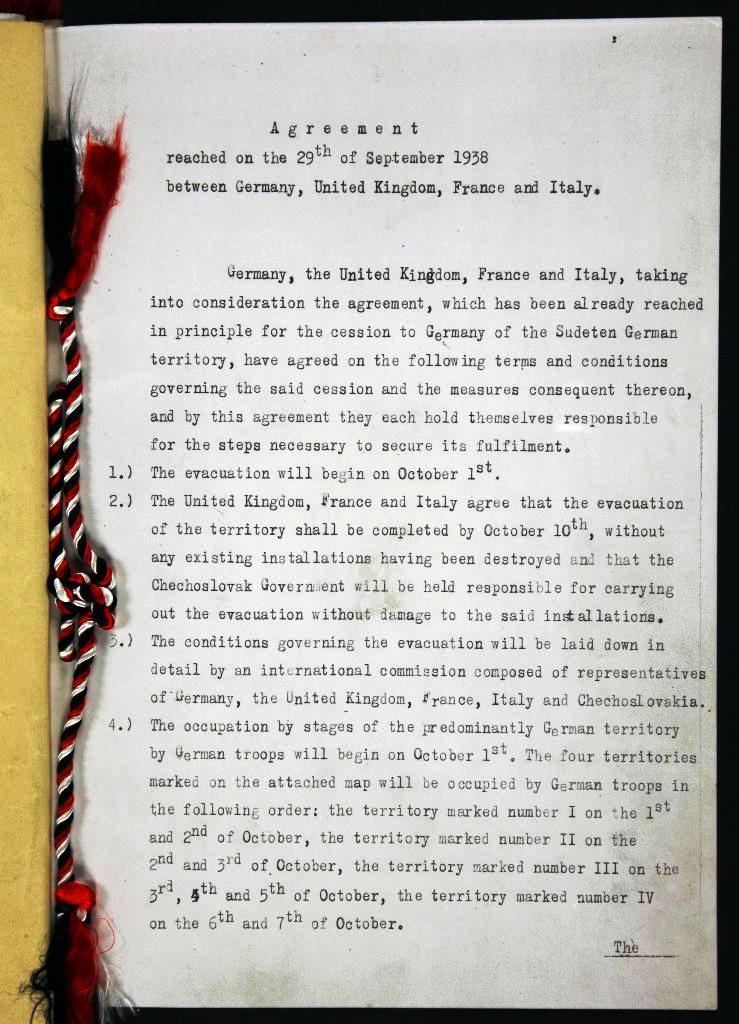

Following further demands and negotiations, the matter culminated in Munich on 29 September at a meeting between Chamberlain, Hitler, and the Italian and French Prime Ministers, Benito Mussolini and Édouard Daladier. The Czechoslovakian leadership was excluded.

The map was given to Chamberlain by Hitler at Munich. It is annotated with dark blue lines to mark the four areas that Germany intended to absorb. These areas are numbered and dated with the days when the German army was due to occupy them.

In terms of the Munich Agreement, the four leaders agreed that German troops would take control of the four areas and other ‘territory of predominantly German character’ between 1 and 10 October. [ref] 2. This was a slightly longer timescale than suggested by the handwritten dates on the map. [/ref] The agreement also provided for the setting up of an international commission to carry out a plebiscite in areas yet to be specified. The final clause of the treaty states that the Czechoslovak government would release German Sudeten political prisoners and others serving in its army and police.

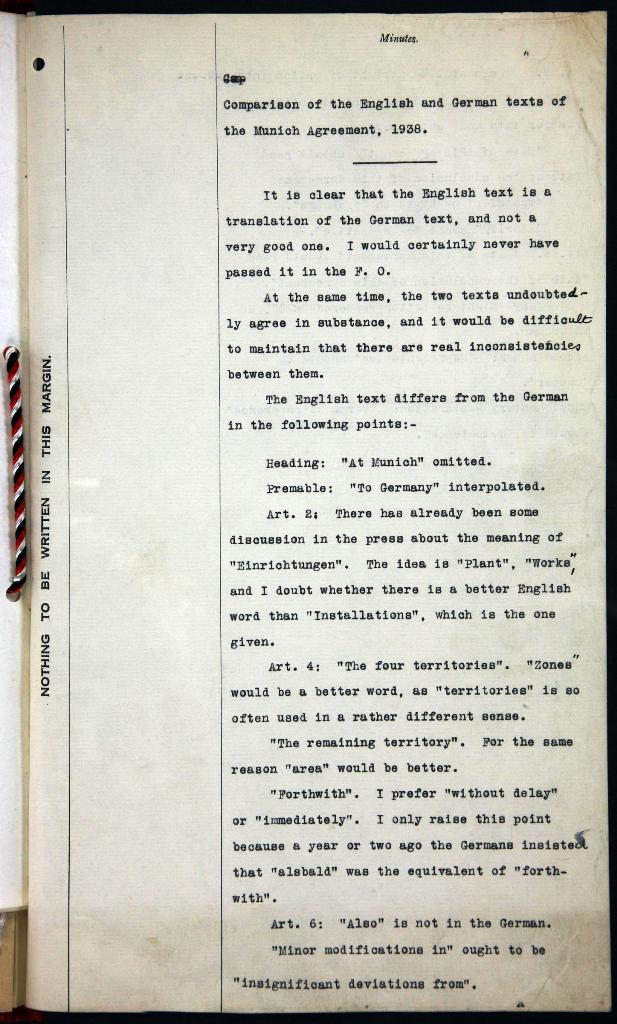

A minute discussing the precise meanings of some of the terms in the text is filed with the agreement.

An authenticated photographic copy of the agreement [ref] 3. FO 93/1/220A. A transcription of the text of the agreement is available on the website of Yale Law School’s Avalon Project. [/ref] signed by Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini is held at The National Archives. The file which holds the agreement incorporates some additional material, including a note interpreting the meaning of particular terms used in the German version.

On Friday 30 September, Chamberlain signed an Anglo-German agreement of co-operation with Hitler. He returned immediately to London, apparently convinced that he had achieved ‘peace for our time’, explaining matters to the Cabinet at its meeting during the evening of the same day. [ref] 4. CAB 23/91/11. [/ref] Chamberlain also had the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Edward Bridges, circulate a memorandum explaining how the terms of the Munich agreement differed from Hitler’s earlier demands expressed in his ‘Godesberg Memorandum’ of 23 September. [ref] 5. CAB 24/279/12. [/ref]

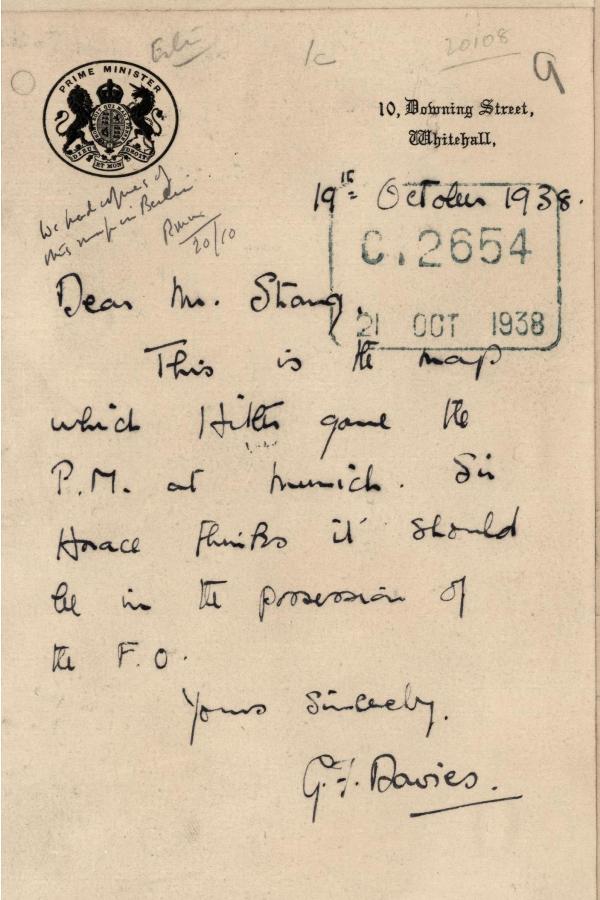

This letter, which attached to the map, explains its origins and how it came to be added to the Foreign Office’s map collection.

At the suggestion of Sir Horace Wilson, the head of the British Civil Service, the map that Chamberlain had received was added to the Foreign Office’s map collection. [ref] 6. This now forms record series FO 925 here at The National Archives. [/ref]

Chamberlain’s prediction of a lasting peace could not have been less accurate. The Munich Agreement preceded the breakup and invasion of Czechoslovakia by Germany in March 1939. Following the subsequent invasion of Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

The Munich Agreement has been interpreted as a major failure of the policy of appeasement, which encouraged further aggressive actions by Hitler. It has also been argued that the postponement of war with Germany gave the British government another year to build up its armed forces.

Was working on FO 1050/1454 this week. It contains details of prayers offered by the Confessional Church in Germany on 27 September 38. They were reported on by the Gestapo as being anti-state. Details were included in a report dated August 1945 to the Church section of the Control Commission in the British Zone in Germany.

Thank you for your comment, Peter. That’s an interesting additional detail and a fine example of how varied the information in our records can be.

Sir Horace Wilson’s own papers are in T 273/403-409 and he was not the Official Head of the Home Civil Service until 1939 when Sir Warren Fisher retired as the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury and therefore the Official Head of the Civil Service. Wilson was acting for Chamberlain as his adviser on Germany as the Foreign Office did not agree with him. The argument that that Britain needed another year to fight Germany (it did but that was not the reason for the Peace Treaty, Chamberlain clearly trusted Hitler) but the papers show that this was not the case and it was Churchill who saw the writing on the wall and Fisher who had warned of the dangers of Germany. Fisher in a briefing to a Cabinet paper had argued that Britain could not fight Germany, Italy and Japan at the same time and that Germany was the main issue and decrying the Air Ministry would worked on the basis of Britain having parity to the levels of the German Air Force.

David, thank you for your correction about Sir Horace’s role at time of the agreement. You are quite right. (I wrote that particular sentence so Dan, my co-author, is not to blame.)

The last paragraph our our post alludes to the fact that historians have placed different interpretations on the wider significance of the meeting at Munich and other events of that time. Ultimately, the records say what they say. The relevance and broader significance of the information that they contain is something that researchers must decide for themselves.

If you liked reading this post, you also might be interested in a related post on the History of Government blog. https://history.blog.gov.uk/2013/09/30/whats-the-context-30-september-

1938-the-munich-agreement/

How can one obtain replica copies of the Munich agreements signed by the 4 delegates and any addendums.

Catalogue reference: FO 93/1/220A.

Thank you for your comment, Peter.

You can order copies of our records using the copying form on our website: https://apps.nationalarchives.gov.uk/recordcopying/

How can I get copies (in all 4 languages) of the Munich Agreement to use in my History classes. I have been searching forever to find this.

Where can I find replica copies of the Munich Agreement, I have been searching forever for these copies in all 4 languages

Thank you for your comment, Peter.

When you left a similar comment back in January, my colleague and co-author Dan Gilfoyle replied to you by email with a couple of suggestions. For the benefit of other readers, this is the gist of his reply.

We do not hold foreign language copies of the agreement. You could try contacting the national archives of the other countries that were signatories to the agreement for advice about these.

As I mentioned in my response to an earlier comment, you can order a copy of the English-language version that we hold from our record copying service.

Alternatively, a transcription of the English-language text is available on the Avalon Project website: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/munmenu.asp

Good luck with your future research.

wow, this post impressed me very much.I think this post will help everyone like me.

Does the National Archives shed any light on if and when Chamberlain had been briefed on Hitler’s secret speech to his generals on Nov. 5, 1937 about his plans for European conquest (entered in evidence at the Nuremberg Tribunal by the Americans from captured German archives as the Hossbach Memorandum)?

French Intelligence had been informed about it by their Berlin asset Hans-Thilo Schmidt the very next day, and they had informed their government immediately and by early 1938 MI6 as well (the Paris resident as well as deputy director, and later director Sir Stewart Menzies).

We know this in such detail from Paul Paillole’s 1985 book Notre Espion chez Hitler (the English translation was only published in 2016).

If Chamberlain had been briefed before Munich, and MI6 would have been very derelict in their duties if they hadn’t, then there is no way Chamberlain could really have trusted Hitler to respect any agreement. If he had after being briefed, he was a greater fool than posterity has even accused him of being until now. Or he was simply buying time, as Gen. Ismay had advised him to do, to build up RAF capabilities.

Knowing this would substantially improve history’s judgment of Chamberlain.