This story, like many unconventional research journeys, starts with an uncatalogued record.

In the autumn of 2014, I was working in the British Library, following up a reference to a periodical called The World’s Fair. Still in the first month of research for my doctoral dissertation on the history of 20th century British retail markets, I was frustrated by seeming paucity of one of the key organisations in my dissertation: the National Market Traders Federation (NMTF). With no institutional archive, the NMTF appeared a brittle backbone for an extended investigation.

Yet the moment I opened the 1925 volume of The World’s Fair, my project changed forever. In each World’s Fair weekly was a supplement called the ‘Market Trader’s Review,’ the official periodical of the National Market Trader’s Federation. This was the institutional source I had been searching for, hidden in a cataloguing anomaly.

For roughly a month, I read the run of the Review from the mid-1920s through the 1970s. While many of the articles, editorials, and letters to the editor confirmed what I already knew about the history of markets in 20th century Britain, there was one hot-button topic that had never appeared on my radar during preliminary reading and research: the proliferation of private markets during the 1970s.

Unlike the majority of ‘public’ markets, run by local authorities by virtue of historic charters or franchises, ‘private’ markets were owned by firms who might manage a portfolio of different market sites across the country. The NMTF was wary of these rival institutions, which often traded without council or planning department permission. In addition, many of these businesses operated on Sundays rather than the traditional market Saturday, therefore challenging the jurisdictional and the religious-cultural underpinnings of market life.

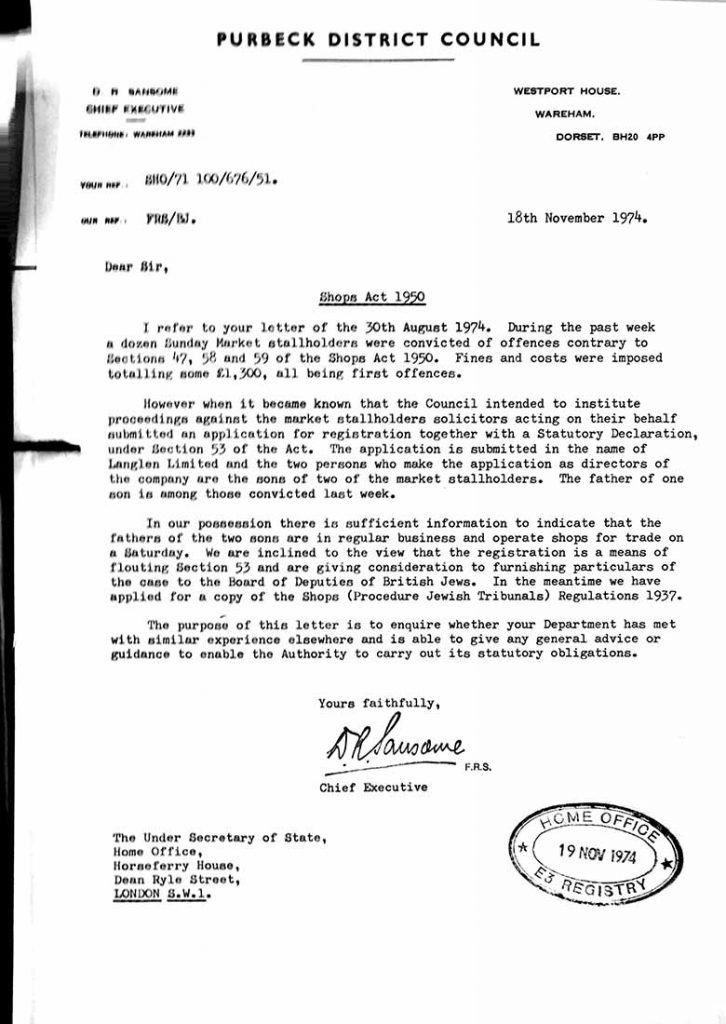

With new key phrases like ‘private market’, ‘Sunday market’ and ‘Sunday trading’ I travelled to Kew to explore the national responses to this challenge. Home Office files on the Shops Act 1950 (HO 308) proved to be particularly illustrative of the complex relationship between local councils, national bodies, and religious organisations in the fight to keep private markets from abusing Sunday trading concessions in England and Wales. From East Yorkshire to Dorset, councils wrote to the Home Office asking them how to proceed with market companies who registered as Jewish-majority operations.

- Letters from Purbeck district council to the Home Office regarding registration under Section 53 of the Shops Act 1950 (catalogue reference: HO 308/48)

- Letters from North Wolds district council to the Home Office regarding registration under Section 53 of the Shops Act 1950 (catalogue reference: HO 308/48)

This Home Office correspondence reveals why and how The National Archives refract issues of the periphery back to the central state, and vice versa. Many local district councils had little idea how to assess who could legitimately trade on Sundays. Jewish trading concessions were traditionally concentrated in London, but as businesses started to take advantage of religious concessions, district councils were compelled to consult the letter of the law in the Shops Act.

Additionally, these files reveal that the enforcement of Sunday trading was by no means uniform across Britain. In particular, references to the lack of Sunday trading restriction in Scotland underscore the need to be specific about which national legislative tradition we mean when we examine the connection between the state, the law and religious bodies.

Fortunately, Glasgow was my next research stop. While I had originally planned to visit the city to study its famous Sunday market, the Barrows, the ‘international’ stakes of the 1970s Sunday trading debates broadened my inquiry. For example, the records of the Scottish Retail Distributors Association (SRDA) at the University of Glasgow Archives revealed how this professional organisation petitioned the Scottish government to bring Sunday trading into line with England in order to curb the private Sunday traders who were ‘exploiting the Scottish public’ with their suspect merchandise, noise nuisance and potential for crime [University of Glasgow Archive Services, Scottish Retail Distributors Association collection, GB 248 UGD214/5/1].

Like the NMTF, the SRDA had a stake in curtaining Sunday markets. Yet without the legal recourse of the Shops Act, Scottish retailers and councillors foregrounded both the moral argument against rampant Sunday trading, and the ‘English interests’ who crossed the border to take advantage of the Scottish law.

From London to Glasgow—and in subsequent trips to Bristol, Leicester, West Lothian, and Edinburgh—my research has chased the debates that ensue when entrepreneurs directly challenge the authority of the local state and the business establishment. Because private market traders worked within the grey areas of trading and planning legislation, their opportunism is not conducive to comprehensive or detailed archival documentation.

Yet by reading the confusion and ire they raised in the eyes of local authorities and business competitors, I have been able to recreate a piecemeal picture of an ephemeral institution that thrived on the unevenness of not only local, but also regional and national jurisdictions.

Connecting Collections is a series of blogs by academic researchers, exploring the connections between archives across the UK and around the world.

Related blogs

Stateless history: connecting Palestinian archives

Tracing the political history of Cairo’s coffeehouses