When we think about war, it is usually to remember the men and women fighting on the battlefields. Sometimes we forget the animals who served alongside the soldiers, making the difference between life and death, winning or losing.

In the First World War, thousands of horses across the country were requisitioned and taken from farms, liveries, and hunt stables, and from private ownership, as we saw in the film and book ‘Warhorse’.

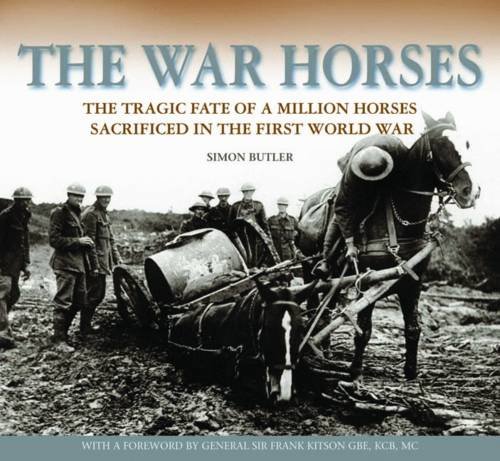

The War Horses by Simon Butler

The British Army took almost a million but by the end of the war, only 60,000 returned. ‘The War Horses: The Tragic Fate of a Million Horses Sacrificed in the First World War’ tells the story of the part these animals played and the consequences of the conflict, which later led to the decline of horses in Britain. It concentrates on the groups of animals who were requisitioned rather than those ‘professionally’ employed by the cavalry – in other words, the horses and mules who took on the drudgery of heaving rations, guns and munitions up to the front line.

From the millions of horses that were killed in the Great War, there was one that did get away: a horse called ‘Warrior’. This is the ‘true story’ of a very special thoroughbred, with an extraordinary character, ‘the horse the Germans could not kill’, (Times, 1941). Warrior managed to survive five years of bombs and bullets, through the Battles of the Somme and Passchendaele with some unbelievable twists of fate. His rider was Winston Churchill’s great heroic friend, Jack Seely, who went to France in 1914 with Warrior. They were an inseparable duo and served together until 1938.

Across all the regiments in the armed services animals became a source of comfort and a morale booster for the troops away from home: hence the mascot. Cats (mousers) were used by the Royal Navy to kill vermin and they were also said to have magic powers to protect ships from dangerous weather. A menagerie of lions, tigers, goats and monkeys were kitted out in regimental uniform as mascots, including a small black bear called Winnipeg. She came to England as a mascot with the Canadian Cavalry Regiment, ending up at London Zoo. It was there that she was spotted by Christopher Milne who named his toy bear after her – and thus she was later to become the inspiration for A A Milne’s character, Winnie the Pooh… the rest is history.

In 1914, dogs were being trained up as ambulance dogs, using their acute smell and hearing to find the wounded soldiers in no-mans-land, bearing the Red Cross Insignia and carrying medical supplies and water. For children of primary school age, ‘Flo of the Somme’ is the story of a Mercy dog, a hero of war. It tells the story of pilots who are shot down during the war and then are saved by the Medical Corps, with the help of a messenger pigeon, a donkey and of course, Flo. This is an award winning book and beautifully illustrated.

At the end of the First World War, many former cavalry horses were brought to the Middle East, as it was too costly to bring them back to England. In 1930 Dorothy Brooke, a wealthy socialite, went to Cairo, where she discovered thousands of British War horses suffering from neglect and chronic disease. ‘The Lost Horses of Cairo’ chronicles the lives and eventual rescue of these horses and describes the challenges of founding and maintaining the The Old War Horse Memorial Hospital, which still exists today. It’s a true and inspirational story.

Although animals were used on the front line and in major battles, animals were also pets and workers; they were on the farms and down the mines. In September 1939, as Britain began to prepare for the Second World War – sewing the blackout curtains, digging up the flower beds for vegetable patches and sending children away to the countryside – 400,000 family cats and dogs were put down. ‘The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War Two’s Unknown Tragedy’ explains what happened and the reasons why. Through gripping stories of shared experiences of bombing and food restriction, it draws extensively on new research from animal charities, state archives, diaries, and family stories. This book does more than tell a virtually forgotten story, but is perhaps is not for the faint-hearted.

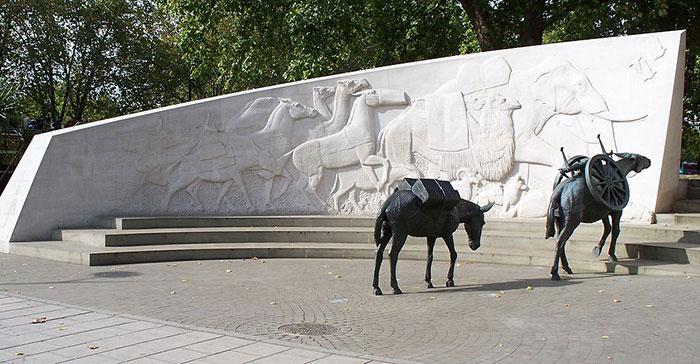

For all those animal lovers there is the Animals in War Memorial at Brook Gate, Park Lane, London W1, which bears the inscription ‘They had no choice’.

By Iridescenti (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Although animals were used on the front line and in major battles, and in other things too

I have a copy of My Horse Warrior illustrated by Alfred Munnings and signed by the author’s wife Do you know anything about Jones the Horse? I learned about this horse which also came all through the first world war in a talk about the Pet Cemetery at Hyde Park but subsequently have come to a dead end in my search for information. The Royal Parks suggested that you might have some reference. Thank you