Have you ever written an email in anger or in jest, and then decided it would be better not to send it? Where do your drafts go? And if a social historian were to compare it with the sent version of the email in years to come, what would they think? And what if only the draft survived – would it present you in a drastically different light?

Here at The National Archives we can make such a comparison for none other than Queen Elizabeth I, as we hold a draft letter addressed to the earl and countess of Shrewsbury that was evidently considered to be too frivolous to be sent, while the final version of the letter survives in Lambeth Palace Library. 1

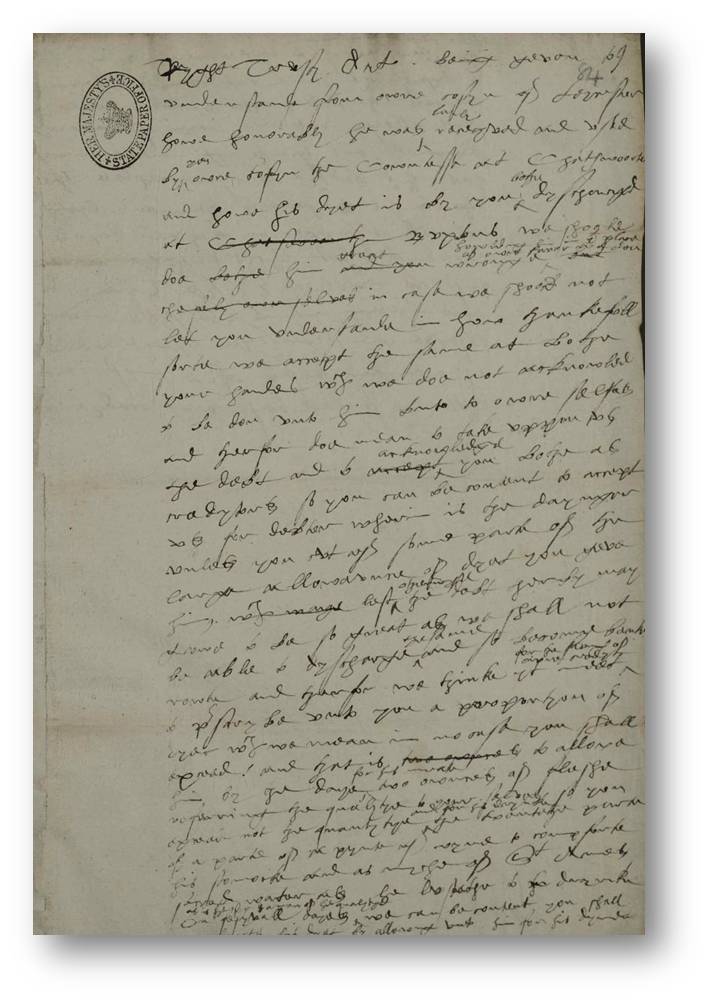

First page of the draft letter from Elizabeth I to the earl and countess of Shrewsbury, SP 53/10 folios 9-12 (item 84)

The letter was intended to thank the earl and countess for the hospitality they had given to Elizabeth’s favourite, Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, during his stay at Buxton, one of their Derbyshire residences, to take the spa waters. The earl and countess owned many properties in Derbyshire and the countess may be more familiar to you as Bess of Hardwick, the indomitable matriarch and builder of both Chatsworth House and Hardwick Hall.

The draft is dated 4 June 1577 and is written in Elizabeth’s own hand. It begins by thanking the earl and countess for how ‘honorably’ Leicester was ‘received and used by you our cousin the countess at Chatsworth and how his diet is by you both discharged at Buxtons’. As Elizabeth holds Leicester in such high favour she is particularly pleased at their kindness towards him. So far, so straightforward for a royal thank-you letter. But in the next line Elizabeth begins to play around with the convention of thanks and obligation, writing that as she considers herself in debt to them for their hospitality, there is a danger that ‘unless you cut off some part of the large allowance of diet you give him…the debt thereby may grow to be so great as we shall not be able to discharge the same, and so become bankrout [ie bankrupt].’

To prevent this fiscal disaster Elizabeth has a practical suggestion. Instead of providing him with a luxurious menu, they should instead restrict his diet, allowing him two ounces of meat a day – and not the good stuff. For drink he can have ‘the twentieth part of a pint of wine to comfort his stomach’. On festival days they can be more generous, and he is allowed for his dinner ‘the shoulder of a wren, and for his supper a leg of the same besides his ordinary ounces’. The same goes for Leicester’s brother, Ambrose Dudley, who is to be provided with ‘light suppers’ as they ‘agree the best with rules of physic’. If they obey her she will be ‘a most thankful debtor to so well-deserving creditors’.

Elizabeth is poking fun at Leicester’s reputation as a healthy eater, as he was known for his preference for light suppers over feasts, and he may even have been responsible for setting an early fashion for salad. 2 While jokes about Leicester’s eating habits may have amused the earl and countess, her references to the debt she owes them would have been no laughing matter. As the guardians of Mary Queen of Scots the couple had been forced to foot the bill for the Queen and her entourage, with Elizabeth providing little in the way of financial aid. And this was no everyday guest they needed to provide for, but a prisoner with queenly demands. Mary was served two courses for both her dinner (usually served between 11am and noon) and her supper (the evening meal), and each of these courses contained 16 dishes from which she could take her pick from, for example, ‘soup, veal, beef, mutton, pork, capon, goose, duck and rabbit…quails, pigeon, tart and frittered apples or pears.’ 3

So jokes about limiting the diets of their guests probably cut rather too close to the bone. In the sent version of the letter, dated 25 June 1577, we can see that Elizabeth decided it was a safer bet to instead stick with a more conservative thank-you letter. She begins the letter in a similar style, by aligning any service done to Leicester with a service done to herself, describing him rather wonderfully as ‘another ourself’. But instead of teasing the earl and countess she reiterates her debt to them for their care of Mary Queen of Scots and states how this has enabled the country to ‘enjoy a peacable government, the best good hap that to any prince on earth can befall’ and promises to repay them ‘when time shall serve’. Despite this promise they never did fully recoup their costs, and eventually the financial and political pressures of their role as guardians and the constant need to defuse her various plots and intrigues took its toll on Bess and George’s relationship, and ultimately led to their separation.

In the draft we see Elizabeth’s mischievous and whimsical side, but also insensitivity to the situation of her loyal subjects. It stands in stark contrast to the final version of the letter, suggesting that the draft process could serve as a creative outlet for its own sake and would never have been intended to be sent. Elizabeth’s affection for Leicester is evident, and although he is the subject of the letter the tone so captures the flirtatious and affectionate dynamic of their relationship that is almost as though she is writing with him in mind as her audience.

To have the draft without the final copy would have skewed our understanding of how Elizabeth treated her most loyal servants, and yet to have the final copy without the draft would deny us a glimpse of the flights of fancy that the queen was capable of. For 21st century readers the retention of both copies is a positive treat, and may make us think twice about deleting our own drafts.

‘Unsealed: The letters of Bess of Hardwick’ is on display in our reading rooms until 2 March 2013.

Notes:

- 1. The reference for the draft letter is The National Archives, State Papers 53/10, folios 9-12, (item 84). The reference for the sent letter is Lambeth Palace Library, MS 3206, folio 819. All quotations from the letters are from modernised transcriptions in Elizabeth I: Collected Works, eds Leah S. Marcus, Janel Mueller and Mary Beth Rose (London: University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 229-231. ↩

- 2. Simon Adams, ‘Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester (1532/3-1588)’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ↩

- 3. John Guy describes her diet in My Heart is My Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots (London: Fourth Estate, 2004), pp. 444-445. ↩

The drafts of letters and the like are important perhaps more than the final version, two cases spring to mind – the telegram on the loss of Apollo 11 if it failed to return to Earth in 1969 and the expected succesful outcome of the Arnhem operation in 1944, did they not consider it could fail?.

This is very interesting web site…this is the first time here…This is awesome post…. signed history finadict.

Thank u