In 2008, friends invited me to look at a collection of family documents relating to dye manufacture in 19th and 20th century Leeds. As a professional artist and tutor working with textiles I had considerable practical experience using natural dyes and was interested in their individual histories, but had never taken it further. An invitation to view an archive changed the course of my life.

A dozen or so trunks emerged from the friends’ attic before a house move. From first glance it was exceptionally interesting and I recognised the urgency to assess and list the contents, because its immediate future was storage in a Devon cob barn. The work took me six dusty weeks. One result was that the major part of the collection has found a home with the West Yorkshire Archive Service.

The other was that I had become an unfunded, independent scholar. In the initial sorting period I became passionately absorbed by documents relating to a natural dye called orchil, a purple dyestuff derived from various lichens. The samples, documents, patents and letters offered fascinating insights into aspects of 19th century trade. I was utterly hooked.

The archive revealed that around 1820 the enterprising Bedford family began the successful manufacture of orchil. I found that their company survived and prospered for 150 years, successfully negotiating the transition from natural to synthetic dyes. It finally went into liquidation in the early 21st century, by then styled as Yorkshire Chemicals, and never underwent a takeover.

A significant item from the archive was a botanical collection of dye-producing lichens mounted on separate sheets, with French annotations in distinctive handwriting. These lichens had been collected mainly in the Canary Islands, historically a major source. The collection had been sent to Leeds after 1850. I took it to mycologists at The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew who later invited me to co-author the historical elements of a paper. Painstaking research on identification and historical naming was subsequently undertaken by Dr Begoña Aguirre-Hudson. Together we benefited from the extensive reference collections at Kew, and the Department of Botany at the Natural History Museum, London.

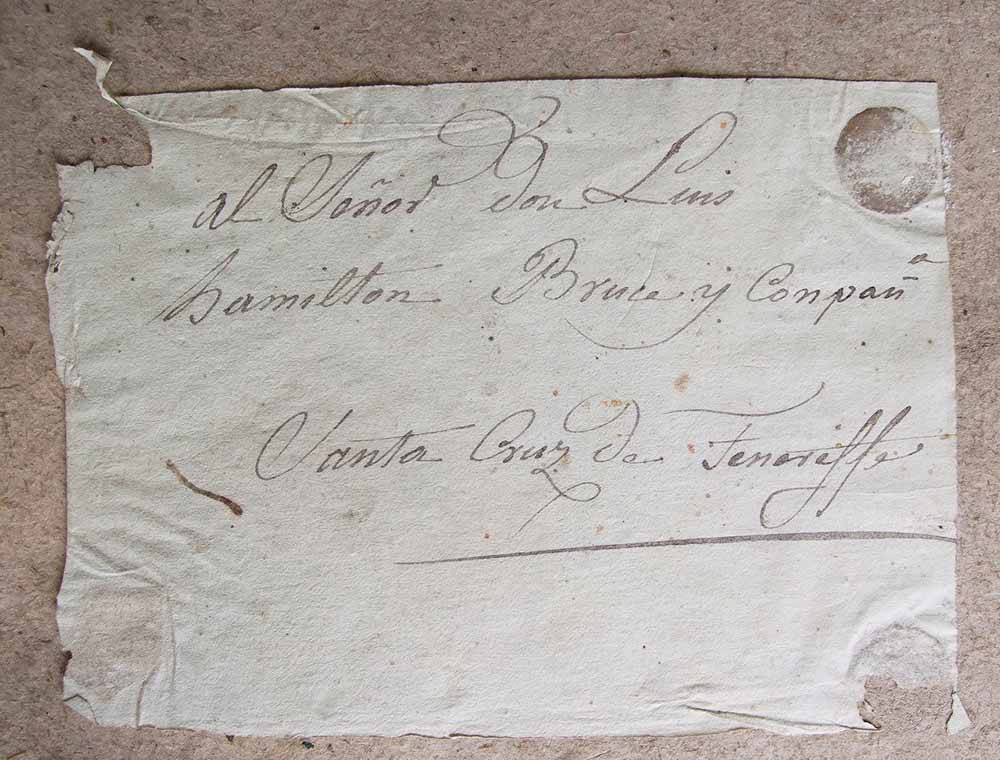

Label on outer covering of the J.M. Despréaux lichen collection, now held at the Economic Botany Collections, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (image credit: Isabella Whitworth)

My own aim was to establish who had made the collection, for what reason, and why it ended up in Leeds. I started with the handwritten label on the outside cover of the collection, in identical handwriting to the notes in French.

To my surprise, I discovered that the shipping company ‘Hamilton y Compañia’ still operate and information was available online. ‘Don Luis Hamilton Bruce’ was not one person as I had thought, but two. Lewis Gellie Hamilton and Gilbert Stewart Bruce founded a company in Tenerife, initially involved in exporting wine and dyestuffs such as cochineal.

Among thousands of documents in the archive were several letters to the Bedford family from a Mr G. C Bruce of Surbiton. One of them described an 1839 search for commercial sources of lichen in Ecuador. Could there be a link between Mr G.C. Bruce of Surbiton and Gilbert Stewart Bruce of Tenerife? A key connection was made using census records held by The National Archives. I searched for various members of the family, from 1851 – 1891, and concluded (I still remember my childish excitement) that George Crossthwaite Bruce of Surbiton was born in Tenerife. He was the son of Gilbert Stewart Bruce.

Regarding the identity of the botanist who collected the lichen, one specimen was dedicated to P. Barker-Webb and my Kew colleague deduced it very likely that J.M. Despréaux had been the collector. In online searches I discovered the online Humboldt Project, whose collection contains a digitized series of letters from Despréaux to Barker-Webb. Finding images of these letters freely available was another breakthrough moment: the distinctive handwriting of the letters, and the botanical annotations, were unmistakably the same. We had found our botanist.

Further research suggested that traders looking for new dye lichen sources might carry actual samples facilitating identification on a like-for-like basis. European lichen stocks were severely depleted in the early 1800s and George Bruce may have acquired or commissioned the Despréaux lichens as a reference collection before venturing to South America. The amicable relations apparent between Bruce and the Bedfords are a possible basis for its eventual dispatch to Leeds.

The joint paper was published in 2011 by the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society; I have since published other papers and given conference presentations. Despréaux’ beautiful botanical specimens of dye lichens are of significant scientific value and have since been accepted into the Economic Botany Collections, Kew.

Connecting Collections is a series of blogs by academic researchers, exploring the connections between archives across the UK and around the world.

Related blogs

Stateless history: connecting Palestinian archives

Tracing the political history of Cairo’s coffeehouses

The Glubb Pasha papers: a precarious existence

On the trail of Henry VIII… in Italy

Sunday trading controversies: private enterprise meets public oversight

An irrelevancy: I am charmed by the existence of a botanist who is named “Begonia” (or a Basque equivalent of it)!

Thank you for being charmed. Begoña is as delightful as her name..!

[…] “An invitation to view an archive changed the course of my life.” Read on! […]

Thank you so much for passing on the link to my blog.

Congratulations on this fantastic bit of sleuthing! It takes great persistence to get this far with such research, well done Isabella! XX

Thank you for the endorsement. It was a very exciting phase of the research and made up for the hours of slog and many dead ends. When you are an unfunded and ‘unsupported’ researcher, university libraries are not easily available but I have found the internet very useful – providing the source is entirely reliable!

Fascinating account! I wish I cd find anything similar concerning phulkari embroidery of Punjab!