One of the many legacies of the United Kingdom’s colonial past is the number of British-sounding place names to be found in various parts of the world. From Birmingham in Alabama to Canterbury in New Zealand, and from New York to New South Wales, these names reflect the English, Scottish, Welsh or Irish heritage of many of the people who settled in those places.

Even before the UK’s capital hosted this year’s Olympic and Paralympic Games, the most famous British place name of all was undoubtedly London. For today’s blog post, I’ve decided to use a small selection of our maps to illustrate some of the world’s other Londons.

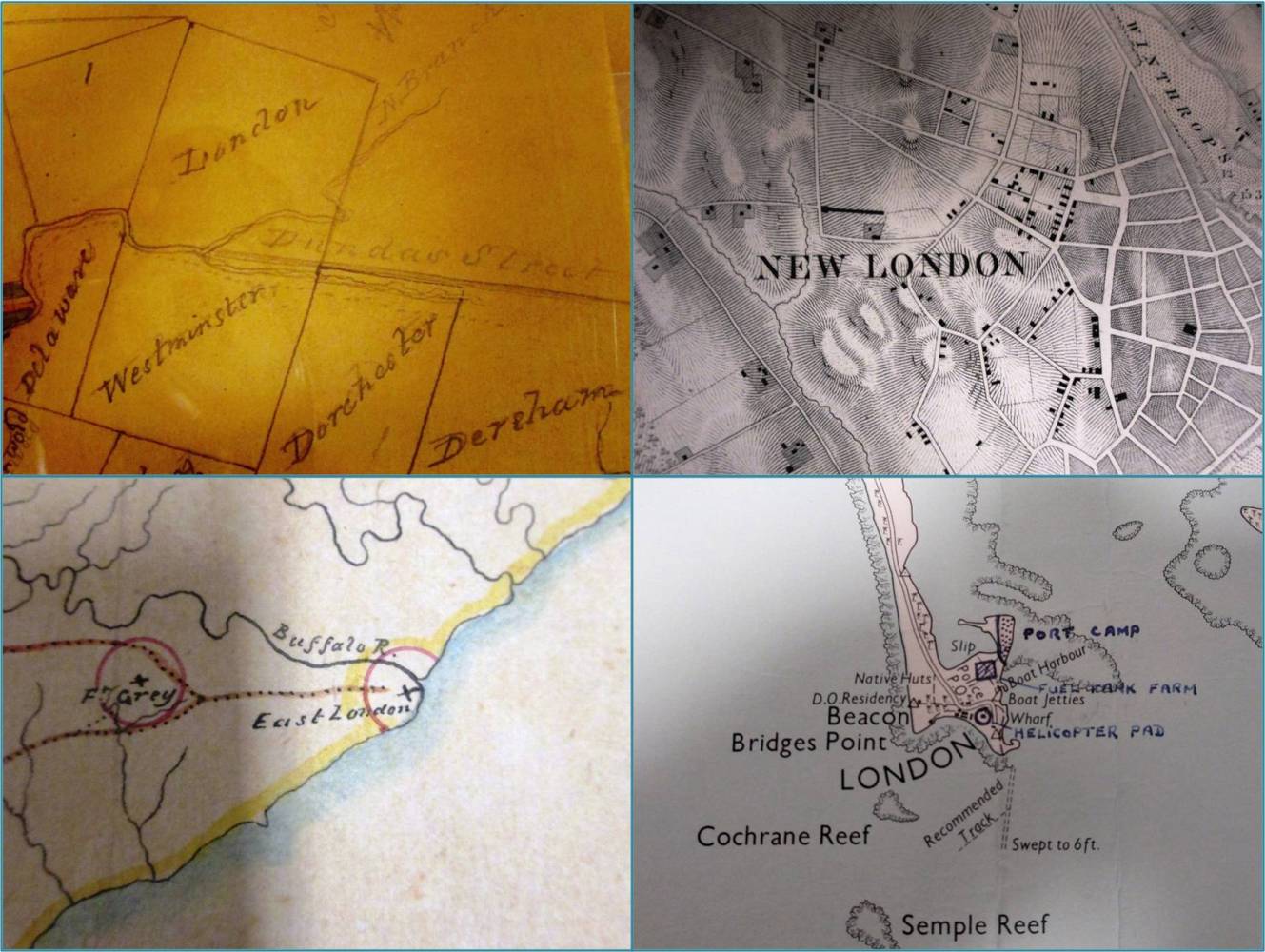

Clockwise from top left: London, Upper Canada (detail from MF 1/30/2); New London, Connecticut, USA (detail from MR 1/1789/26); London, Christmas Island (detail from MFQ 1/1049); East London, Southern Africa (detail from MPG 1/931)

The oldest of the four maps above is the one at the top left (document reference MF 1/30/2), dating from 1820. It is a sketch map, drawn on tracing paper, showing plots of land in the south-western part of what was then called Upper Canada (now the Canadian province of Ontario). This map was originally enclosed in a despatch sent back to the mother country by the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Sir Peregrine Maitland. Many of the English place names marked on it (London, Dereham, Dorchester and Westminster are just a few of them) are still in use in the area today.

Strictly speaking, the map at the top right (document reference MR 1/1789/26) is not a ‘map’ but a ‘chart’ (a map of the sea). It shows New London and adjacent coastal areas, in the US state of Connecticut. Like ‘old’ London, this city lies on a river called the Thames [ref] 1. The name of the American Thames is apparently pronounced quite differently from the English Thames. [/ref]. The chart was published by the United States Coastal Survey in 1848. We hold it as part of a set of charts of coastal areas in North America, which was collated for the Anglo-American Fishery Commission in 1862.

The map on the lower left above (document reference MPG 1/931) shows part of the coast of south-eastern Africa. It was hand-drawn in 1856 and included in Colonial Office correspondence relating to the Cape Colony. At that time, the area around East London was referred to as ‘British Kaffraria’ [ref] 2. This name is now considered offensive because of its etymological connection with the racist term ‘kaffir’. [/ref]. It is now part of Eastern Cape Province in South Africa.

The fourth map above (document reference MFQ 1/1049) is much more recent than the other three, dating from 1956. It is a printed British military map of Christmas Island (now officially called Kiritimati) in the Pacific Ocean. Our copy was annotated in 1957 to show the sites of radio transmitters and landing strips and was included in the Operations Record Book for Royal Air Force Squadron 240. Kiritimati is now part of the independent country of Kiribati; London (also known as Ronton) is the island’s second-largest village.

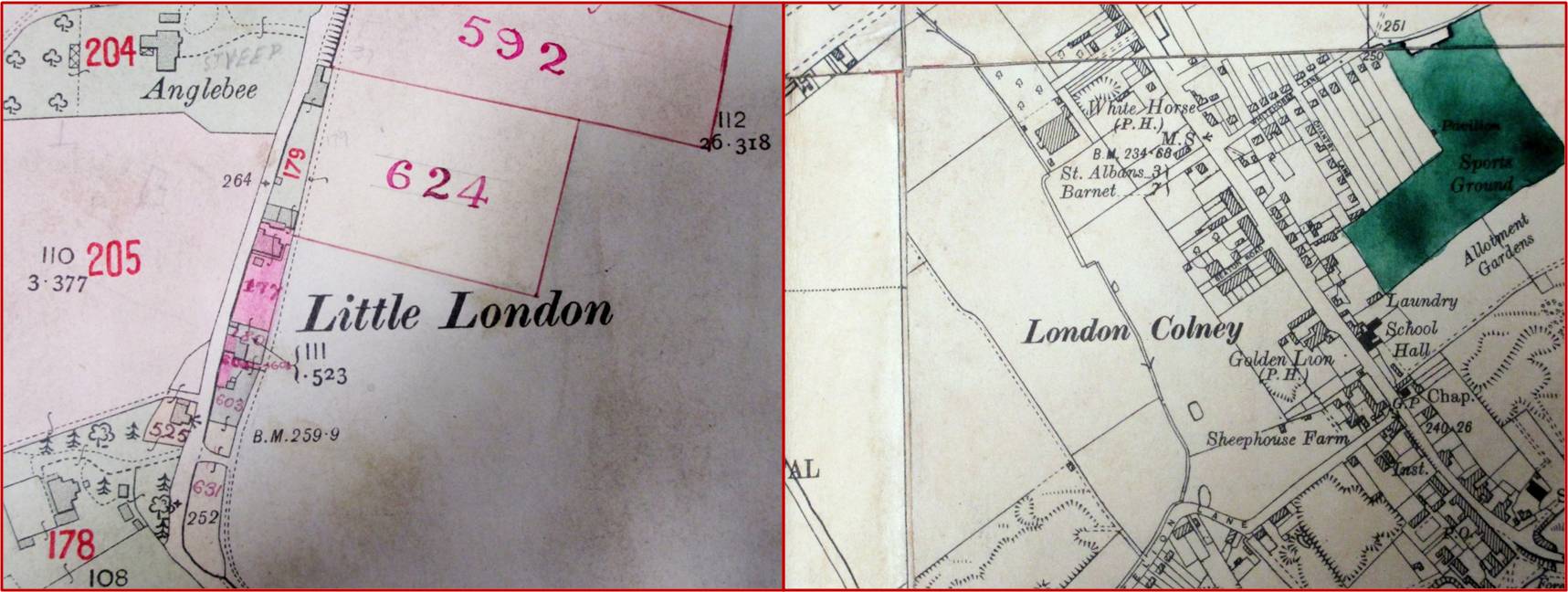

Left: Little London, Berkshire (detail from IR 126/6/25). Right: London Colney, Hertfordshire (detail from OS 38/1479)

Even within the UK itself, there are multiple Londons. For instance, many small settlements in England and Wales bear the name Little London. The example on the left above (document reference IR 126/6/25) shows a Little London in Berkshire [ref] 3. Following a boundary changes in 1974, the area is now in Oxfordshire, but it was in Berkshire at the time the map was made. [/ref] in 1913. This map forms part of the Valuation Office survey.

The map on the right above (document reference OS 38/1479) shows the Hertfordshire village of London Colney. It was produced in 1947 to record a small change in the parish boundary and ensure that Ordnance Survey could show the new boundary correctly on future editions of its published maps [ref] 4. This map is in fact what we call a ‘collage’: it consists of parts of several printed maps glued together to form a larger map and then annotated by hand. For those interested in the specifics of Ordnance Survey mapping, the component maps are six-inch (1:10,560-scale) County Series sheets printed in the 1920s and 1930s. [/ref]. This map now forms part of the Ordnance Survey boundary archive.

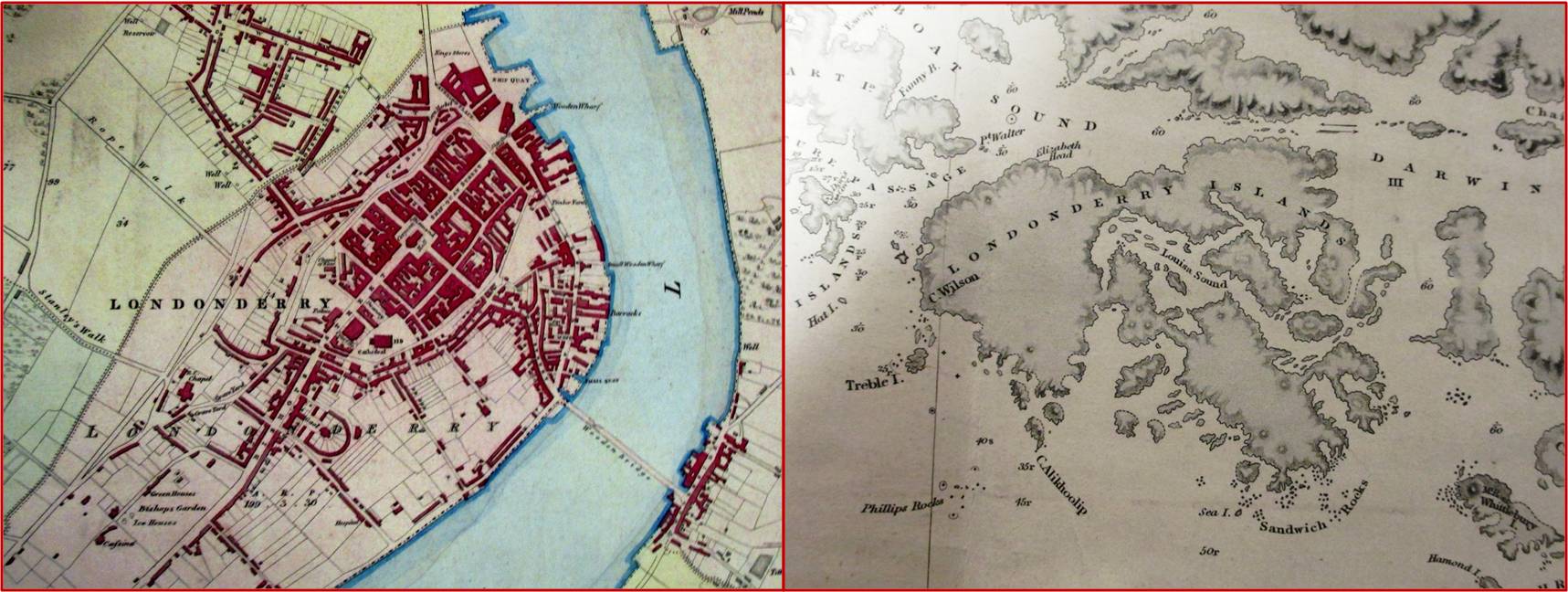

Left: Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland (detail from MR 1/1185). Right: Londonderry Island, Tierra del Fuego (detail from FO 925/1751)

Place names can at times be controversial and one of the most debated and disputed naming issues relates to the use (or non-use) of the element London. Some people call the second largest city in Northern Ireland Londonderry and others call it simply Derry. The use of one form or the other often indicates the speaker or writer’s political views and religious loyalties. Writers anxious not to give unintentional offence sometimes use a combined form, such as Derry/Londonderry [ref] 5. This practice has given rise to the unofficial nickname ‘Stroke City’. [/ref].

The 19th century Ordnance Survey of Ireland, which produced the map on the left above (document reference MR 1/1185) had no such qualms. This map came to us as part of the War Office map collection.

The map on the right above (document reference FO 925/1751) shows a much less controversial Londonderry, an island near the southern tip of South America, now part of Chile [ref] 6. Argentina and Chile signed a treaty dividing the area of Tierra del Fuego between them in 1881, a year after this map was published. [/ref]. The island was named by a British naval captain, Robert FitzRoy, after the Marquess of Londonderry.

Like the map of New London, this ‘map’ is technically a chart, in this case an official British Admiralty chart. It was published in 1880 but was largely based on earlier surveys carried out during Captain FitzRoy’s voyages on HMS Beagle [ref] 7. The second of these voyages was the one made famous by Charles Darwin. [/ref] in the 1830s. Our copy of the chart forms part of the Foreign Office map collection.

The London that everyone knows, albeit from a slightly different perspective (detail from MPF 1/128)

I couldn’t finish without including a map showing the original London (document reference MPF 1/128). I’ve chosen a slightly unusual one. Can you spot what is special about it?

What next?

For budding researchers: Browse our guidance on researching the histories of places

For family historians researching London-based ancestors: Listen to our ‘Lost in London’ podcast

For teachers and pupils: Explore our online exhibition on the British Empire

For book lovers: Read Peter Barber’s new book London: a History in Maps

Elsewhere on the web:

- English Place-Name Society

- Library and archive collections at the University of London’s Institute of Commonwealth Studies

- Archives for London

I assume you mean that MPF 1/128 starts from the south bank of the Thames to the north rather than the usual other way round.

Thank you, David. That’s an interesting way of describing it but, yes, south is at the top of this map.

If you look at the top of the image, you can just see the tip of the compass indicator pointing downwards to indicate the direction of north.