Earlier this summer, MPs debated the UK’s nuclear deterrent. The resulting vote endorsed a government motion to replace Britain’s fleet of Vanguard-class submarines, which provide a continuous at-sea deterrent, with new boats.

Current debates focus on the development of this new Successor-class vessel, but 2016 also marks the 50th anniversary of the launch of Britain’s first ballistic missile submarine (SSBN). 1 On 15 September 1966, the lead ship of the Royal Navy’s Resolution-class was launched, with Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother looking on.

Britain had successfully tested its first nuclear weapon nearly 24 years earlier under the codename Operation Hurricane. From the outset of the British deterrent, responsibility for delivering the weapon fell to the Royal Air Force (RAF) and its V-bombers, comprised of Valiant, Vulcan and Victor aircraft. These planes faced obsolescence by the mid-1960s, however, and the British government looked to develop an alternative.

The RAF’s operational control of the nuclear deterrent was set to continue with development of the Blue Streak medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), but this was eventually cancelled amidst escalating costs and technical drawbacks that left it vulnerable to an enemy first strike. As Harold Watkinson, the minister of defence, stated to the House of Commons on 13 April 1960, ‘we ought not to continue to develop, as a military weapon, a missile that can be launched only from a fixed site’. 2

Prime minister Harold Macmillan and President Dwight D. Eisenhower in Bermuda, 1957 (catalogue reference: CO 1069/268)

Despite this setback, Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government remained committed to Britain’s possession of an independent nuclear deterrent. The prime minister sought to acquire the Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) from the United States, extending the life of the V-bombers in the process. As negotiations over Skybolt progressed, the US Navy was granted permission to use the Holy Loch base in Scotland for its Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) force (PREM 11/2941). Macmillan’s strategy finally saw success at Camp David on 29 March 1960, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower agreed to facilitate a UK purchase of Skybolt (PREM 11/2994). The future of Britain’s deterrent appeared settled.

Skybolt’s future was also soon in doubt, however. It had performed poorly in tests, while Polaris submarines had the advantage of being able to remain undetectable at sea for months at a time. When US defence secretary Robert McNamara opted to cancel the project in 1962, Britain faced the prospect of being left without a nuclear deterrent. With the collapse of Macmillan’s government a possibility, an Anglo-American summit meeting was convened to take place in Nassau, the Bahamas in December 1962.

At Nassau, President John F. Kennedy offered to continue the development of Skybolt for Britain’s use and to contribute to the cost. Macmillan now set his sights on Polaris, however. In light of Skybolt’s difficulties, he famously remarked that while ‘the proposed British marriage with Skybolt was not exactly a shot-gun wedding, the virginity of the lady must now be regarded as doubtful’ (PREM 11/4147).

Eventually a deal was reached in which the United States would supply Polaris missiles – Britain would make its own warheads – but that the submarines carrying them would be assigned to NATO. Crucially however, they could be withdrawn when the British government considered its ‘supreme national interests’ to be at stake (PREM 11/4147). 3

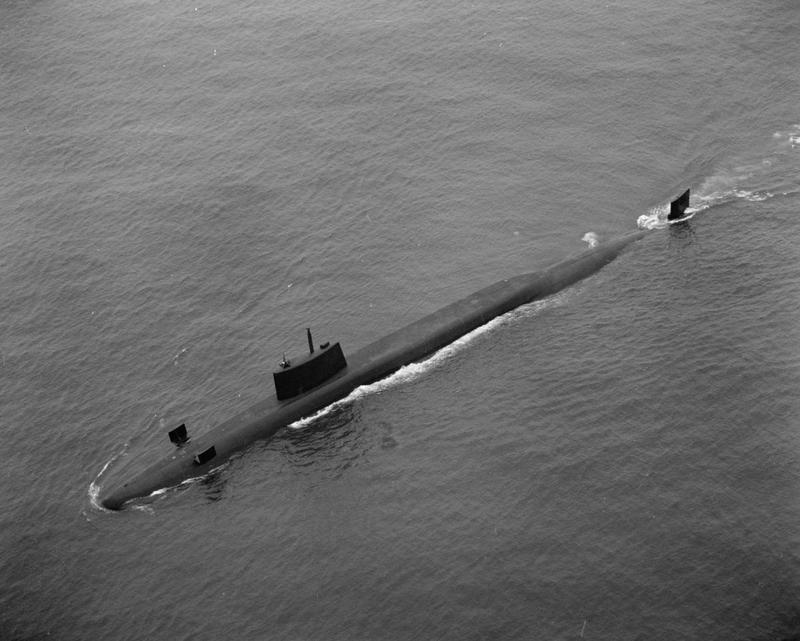

HMS Resolution undergoing speed trials in June 1967. © Crown copyright. IWM (A 35096)

HMS Resolution, Britain’s first Polaris SSBN, was laid down in February 1964 at the Vickers Shipbuilding yard in Barrow-in-Furness. Work continued after the submarine’s 1966 launch and it was commissioned in October 1967. In February 1968, Resolution fired Britain’s first Polaris missile during an exercise off Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral), Florida.

Three further vessels – Repulse, Renown and Revenge – were also produced, with a fifth cancelled by the incoming Labour government of Harold Wilson. Each boat could be armed with up to 16 Polaris A-3 missiles. The A-3 carried three (non-independently targetable) ET.317 nuclear warheads apiece, each of which provided a blast yield of 200 kilotons. In comparison, the ‘Little Boy’ fission weapon used for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima produced 15 kilotons. The fleet was upgraded with the Chevaline system in the 1980s to provide an improved capability for penetrating anti-ballistic missile defences.

The Polaris submarines remained in service until the 1990s, when they were phased out in favour of the current Trident-equipped boats. Towards the end of its operational life, Resolution – which had been scheduled for decommissioning in 1991 – continued to sail while Renown and Repulse underwent repairs. It ultimately survived longer than the newer Revenge, and was decommissioned in October 1994. HMS Resolution is currently laid up at Rosyth Dockyard while awaiting scrappage under the Ministry of Defence’s Submarine Dismantling Programme.

Notes:

- 1. The acronym stands for Ship Submersible Ballistic Nuclear. ↩

- 2. Blue Streak went on to be assigned to the European Launcher Development Organisation and was repurposed as part of a satellite launcher. This is charted in the public information film The Blue Streak Rocket. ↩

- 3. A summary of ‘The “Skybolt” Story’ can be found in the file T 328/88, and the recent BBC documentary ‘A Very British Deterrent’ also reconstructed the story of how Britain acquired the Polaris system. ↩

This is a typical episode of Government defence procurement which typifies the 1960s. Polaris was, of course, opposed by Harold Wilson’s Government and he did not tell his Cabinet what he was doing, and Treasury regarded the project as a waste of money. Holy Loch was from the 1950s and still is a contentious issue in Scotland having been raised in the Scottish Independence Referendum.

There was no substantial change in British nuclear policy under the Wilson government. Despite some of his rhetoric while in opposition, Wilson declined to cancel Polaris once in office despite evidence that it would have been possible to do so without incurring exorbitant cost.

The US naval base at Holy Loch closed in 1992. Britain’s SSBN fleet is based on the other side of the Clyde at Faslane. It is this base, I believe, that continues to be a source of debate in Scotland.

The issue is as O understand it was that the Wilson Government was against Polaris and Wilson did a deal without telling them until it happened. Indeed the base is very much a source of fierce debate (it only moved across the water, why do the governments always seem to send such projects to Scotland) and the recent suggestion that the submarines be moved to Plymouth in the event of Scottish Independence. As one Treasury official said in the 1960s about spending money on something you can’t use without annihilation of the world (later known as MAD).