During my internship at The National Archives, a part of my Masters in Public History at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, I have been analysing the Middlesex Military Service Appeal Tribunal Papers.

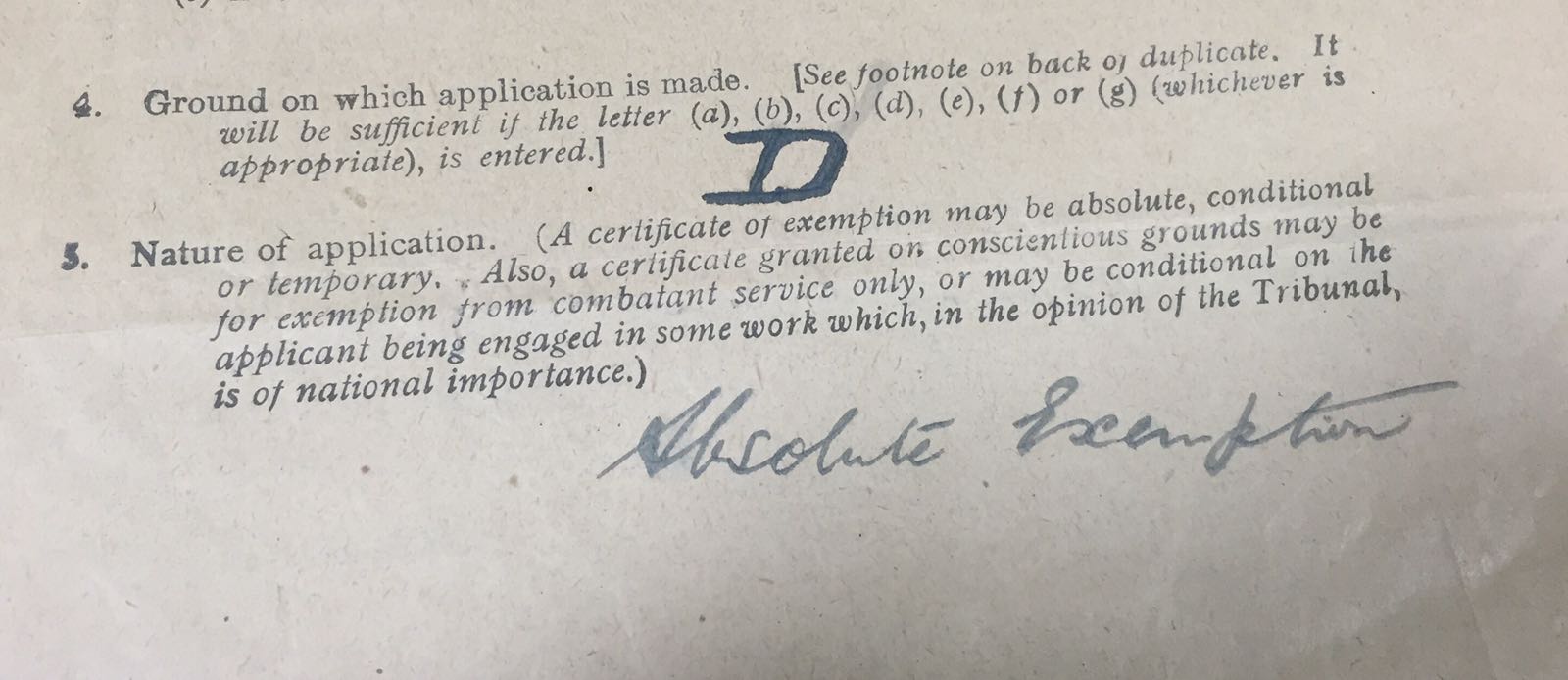

While there are several grounds from which exemption from Military Service could be granted, it is ground D which I find myself primarily interested in: that serious hardship would ensure if the man were called up for army service, owing to his exceptional financial or business obligations or domestic position. I became increasingly interested in what would be considered, by the tribunals, as genuine domestic hardship.

Here are three different cases which ended up at the Middlesex tribunal. All three were claiming exemptions on ground D and can be found in the Middlesex Military Service Appeal Tribunal Papers [MH 47]

A case of genuine domestic hardship

Joseph Benjamin was appealing for absolute exemption in the early part of 1917. Joseph had recently become a widower and consequently sole guardian of his two children, a girl aged seven and a boy aged five. He was appealing for exemption as he did not want to break up his home, leaving his children in the care of strangers.

![Image of confirmation of Benjamin Joseph's employment at the Ministry of Munition Store [MH 47/55/7]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/01152912/IMG_4736.jpg)

Confirmation of Benjamin Joseph’s employment at the Ministry of Munition Store (catalogue reference: MH 47/55/7)

Joseph’s position was indeed regarded by the tribunal as genuine domestic hardship and he was granted conditional exemption, provisional upon him becoming engaged in work of national importance, which needed to be approved by the tribunal. This Joseph promptly did, getting a job at the Ministry of Munitions store at Nine Elms Lane for 48 hours per week.

On 3 March 1917 his conditional exemption was approved after the conformation of his employment was supplied to and accepted by the tribunal.

Appeal dismissed

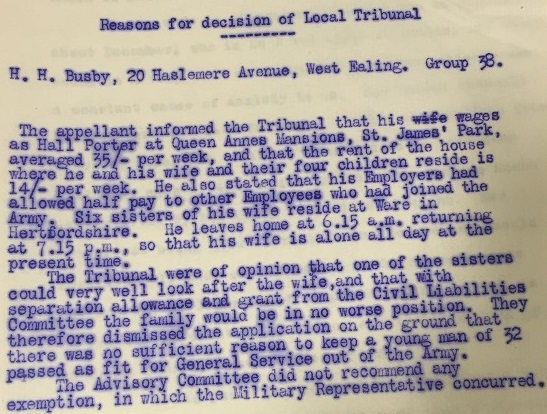

Henry Busby appealed for temporary exemption in July 1916, mainly due to his pregnant wife’s ill health. Henry’s wife was suffering from several maladies, including a weak heart and sudden heart attacks, all of which caused him endless anxiety. His wife’s mother had also recently passed away due to a heart condition, leaving no one to help his wife with their four young children.

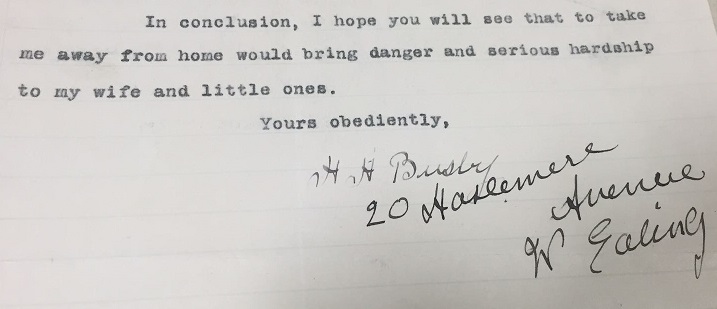

Due to Henry’s financial position, joining the army would not provide the income to pay for another person’s help. This left Henry worrying about what would result if he were called up and his wife left completely alone with the children. As Henry himself puts it:

‘…I hope you will see that to take me away from home would bring danger and serious hardship to my wife and little ones.’ (MH 47/80/85)

Henry Busby’s closing statements on his application for exemption (catalogue reference: MH 47/80/85)

The tribunal felt that Henry’s case did not qualify as genuine hardship. Henry’s present work kept him away from home from 6.15am until 7.15pm, meaning his wife was alone for the majority of the day. It was also stated by the tribunal that with the financial help granted to soldiers, such as the separation allowance, Henry’s family would be no worse off.

Lastly, the tribunal felt that even though they lived in Hertfordshire, one of his wife’s six sisters could easily assist in helping their sister, and looking after his children. Henry’s case was dismissed with no exceptions.

A 14 day exemption

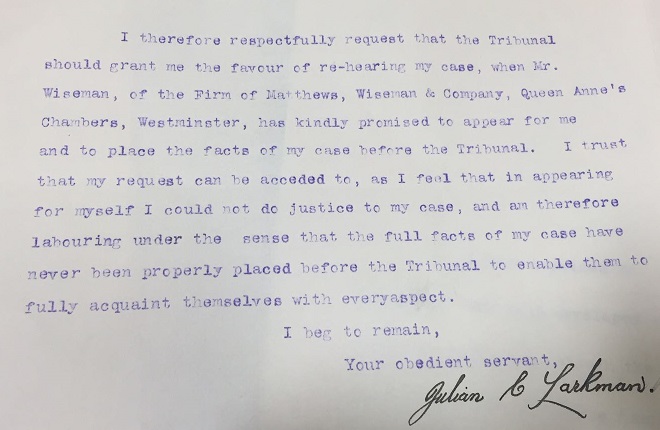

Julian Larkman asking for his case to be reheard by the Tribunal (catalogue reference: MH 47/77/66)

Julian C. Larkman had previously been granted an exemption of 14 days; he was, however, trying to get his case reheard by the Central Tribunal.

Due to Julian being called upon as a juror, he could not present his case to the previous tribunal and his advocate, Rev. James McCleery, was not allowed to speak at said tribunal. Therefore, Julian was hoping to put forward before the tribunal the facts as they stood at the present time. He believed these facts would have ‘the effect of causing the Tribunal to have come to a different decision’ (MH 47/77/66).

His mother and aunt had recently been deprived of one their sources of income due to the death of a relative, leaving Julian along with his sister with the role of helping to aid them. This was something he felt he would be unable to do if he were called upon to serve in the military. Not only this, Julian’s brother was also a conscientious objector who had caused untold strain and stress to his mother. Julian was most anxious these events would steer his mother towards a breakdown.

However, Julian was denied permission by the Appeal Tribunal to have his cased heard before the Central Tribunal, and therefore had only 14 days in which to remedy his situation.

Solutions

The Tribunal’s solutions for Henry Busby’s situation (catalogue reference: MH 47/80/85)

Throughout Henry Busby’s case we can see that tribunals were somewhat hesitant to hand out exemptions; instead, they sought solutions to the appellant’s hardship. Thus tribunals were seeking to appease the appellant’s situation while freeing the man for military service. Many employed by the tribunal services saw their role as patriotic duty to the state, rather than a legal duty to the appellant. As Lois Bibbings notes ‘…their priority was to provide as many men as possible for the military.’ 1

Not only were solutions sought to an appellant’s situation, but almost every case that was given exemptions was conditional upon the men contracting work deem as national importance by the tribunals. Manpower was simply too valuable to dismiss completely: men either joined the war effort, or supported it.

The same but different

While the cases detailed here contain similar themes, they received completely different verdicts from the tribunals. Within the MH 47 series you can find a plethora of cases just like these, who all again had strikingly different success rates with the tribunals. This leaves the feeling that the topic of the blog is somewhat fruitless, for there cannot be a universal standard of genuine hardship based upon the tribunals.

This could be attributed to the ambiguous wording of the act itself: never is it explicitly stated what requirements must be met by applicants stating hardship. No framework was established within the tribunals themselves. Thus the tribunals, who were chiefly ‘…composed of unpaid, middle-aged patriots without legal training’, could make of it what they wanted. 2

The definition of true genuine hardship became fluid within the tribunals, given different meanings and requirements by different tribunal members. This is especially true as the war ground on and the need for men became increasingly dire. Gaining exemptions on the ground of hardship, or indeed on any grounds, became a game of luck.

Benjamin Joseph claiming exemption on grounds D (catalogue reference: MH 47/55/7)

While the First World War is a highly researched time period, the Middlesex Military Service Appeal Tribunal Papers (MH 47) is a somewhat unmined resource. The MH 47 series has a wealth of information regarding British society at a time of great changes; while trawling through you’ll glimpse medical statuses, career paths, religious beliefs, familial structure and so much more. The series gives us the chance to analyse the impact modern warfare had on British society.

If you’re interested in the First World War I highly suggest using the MH 47 series as a resource, it is truly unique.

Notes:

- 1. Bibbings, Lois. ‘Images of Manliness: The Portrayal of Soldiers and Conscientious objectors in the Great War’ in Social Legal Studies (Vol. 12, No. 3, 2003) pp 343 ↩

- 2. Kennedy, Thomas.C. ‘Public Opinion and the Conscientious Objector, 1915-1919’ in Journal of British Studies (Vol. 12, No.2, 1973) pp 108 ↩

It’s genuinely hard for tribunes such as this to be even handed throughout since the appeals themselves are quite subjective. But, one can’t but feel sad for those poor souls who must have faced such situation as the first case here (the father with two very young children).