Working on the many thousands of petitions for clemency in record series HO 17 can be a sobering experience. We find accounts of families torn apart by transportation, descriptions of upsetting crimes, stories of individuals driven to criminal acts in desperate circumstances, and sometimes we come across unsettling accounts of someone who appears to have been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Edward Ashford is just such a case. I have chosen to focus on him for this blog because his petitions provide an unusually detailed account of how events overtook him, and his life was turned upside down: a trip to a fair led to an accusation of theft and the prospect of never seeing his family again.

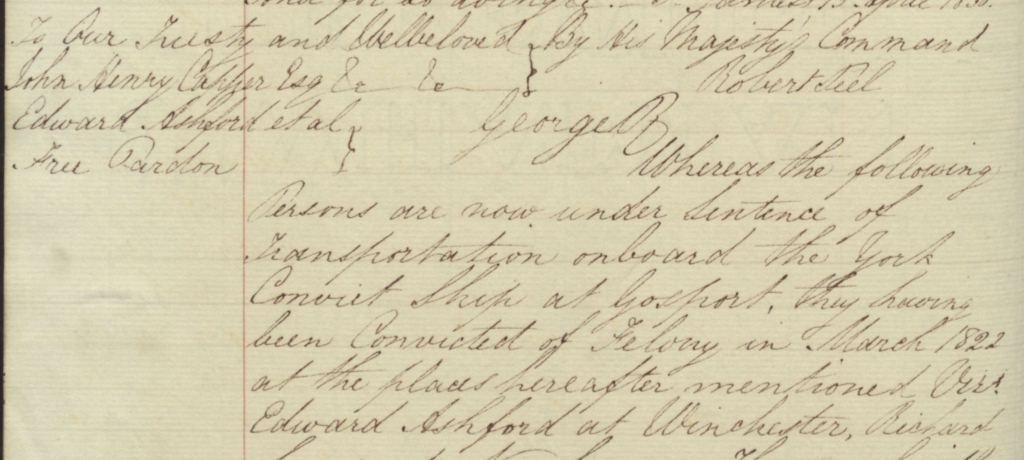

Ashford was convicted at the Winchester Assizes in March 1822 for stealing and sentenced to transportation for life. The petitions on his behalf reveal his helplessness as events appeared to conspire against him.

Ashford was a baker who worked in Portsmouth making ship bread until 1814, when the winding down of the war economy saw demand for ship bread drop; Ashford found himself out of work. 1 No longer able to make a living as a baker, Ashford bought a horse and cart from which he sold fish or undertook carting work. After seven or eight years he heard that a public house was to be let in Salisbury and decided to try his hand as a publican.

While in Salisbury making enquiries, Ashford visited Wickham Fair. Having walked round the fair he stopped for refreshment in a local pub, where:

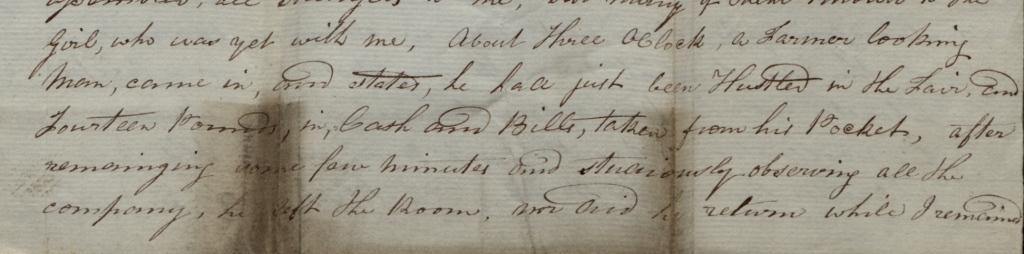

‘About three o’clock a farmer looking man came in and states he had just been hustled in the fair and fourteen pounds, in cash and bills taken from his pocket, after remaining some few minutes and studiously observing all the company he left the room’

A ‘farmer-looking man’ complains of a theft at Wickham Fair (catalogue reference: HO 17/122/138 )

Heading back to Salisbury later that day Ashford stopped in a nearby town for a pint of ale, but finding ‘more company here than I expected, among whom mirth and good humour seemed the “order of the day”‘, he booked a bed at the pub.

Soon after midnight Ashford was disturbed and taken into custody, charged with being accessory to a robbery committed the previous day at Wickham Fair. A woman, who Ashford had met on his way to the fair and spent the day with, was also taken into custody, along with three other men. Although nothing suspicious was found on any of them, the five were taken before a magistrate the next day and remanded so that witnesses might identify them. While the victim claimed to have been so startled he would not remember the culprit, two women, including Mrs Nutbourne, the owner of a gingerbread stall at the fair, felt they would recognise the thief again.

A few days later Ashford and his co-accused were taken for re-examination before the two witnesses, both of whom ‘unhesitatingly declare[d] their conviction that none of us were of the party’. Nonetheless Ashford reports that the two witnesses were ‘requested to divest themselves of all discomposure or confusion, to leave the room a while and again consider if some one or other of us were not of the guilty party’. The women again declared they were not the thieves but the charade continued:

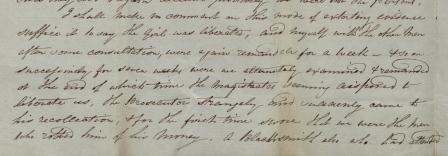

‘for seven weeks were we alternately examined and remanded at the end of which time the magistrates seeming disposed to liberate us, the prosecutor strangely and suddenly came to his recollection and for the first time swore that we were the men who robbed him of this money’.

Ashford describes his treatment as a suspect (document reference: HO 17/122/138)

Another witness now appeared who said that he saw Ashford near the spot at the time of the robbery. The evidence was considered conclusive and Ashford and the other men were committed for trial.

At this point Ashford made what would prove to be a big mistake:

‘the extreme hardship of my case made a forcible impression on my mind, and I hastily (though perhaps ill advisedly) determined on making my escape. This I succeeded in doing, and with all possible speed returned to my family in Somerset.’

After three months Ashford was discovered and re-arrested, his failed escape taken as proof of his guilt.

Ashford’s luck went from bad to worse when his attorney failed to appear at his trial in March 1822. His key witness, Mrs Nutbourne, the stallholder, was subpoenaed to give evidence, but the prosecution attorney persuaded the judge that her evidence was unreliable and her statement swearing that Ashford was not one of the perpetrators carried no weight. Ashford’s escape sealed his fate and he was sentenced to transportation for life.

Unusually, William Tate, Chaplain at Portsmouth Dockyard, took up Ashford’s case, investigating Ashford’s family, the circumstances of the crime and even visiting Mrs Nutbourne, the gingerbread seller to hear her account. He concluded that ‘all circumstance seem to me to concur to render it improbable that Ashford was guilty of the offence’.

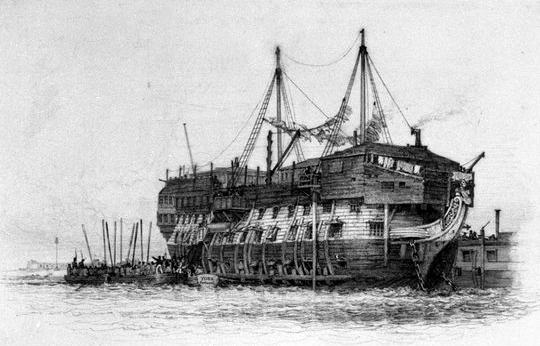

The convict hulk York, where Ashford was held (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The chaplain questions why three men have been transported for the offence when witness accounts record the robbery was committed by a boy and two men only. He suggests Ashford, a stranger in Wickham, fell under suspicion because of his female companion, ‘a loose character, and well known as having been a kept mistress of a major in the Army’. He points to the ‘shameful non-attendance’ of Ashford’s attorney which meant that he ‘certainly had not a fair trial’.

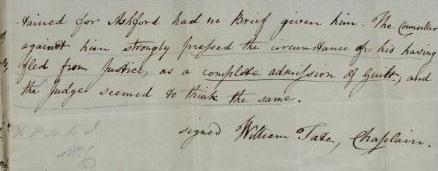

Home Office annotation on Tate’s petition suggesting Ashford’s failed escape proved his guilt (catalogue reference: HO 17/122/138)

Tate’s interventions were in vain. The Home Office seems to have taken the same view as the judge at the trial who concluded that Ashford’s escape was ‘a complete admission of guilt’: a Home Office annotation underlines this point, noting in pencil ‘And so do I’.

Despite these reservations, Ashford’s sentence was reduced to 14 years transportation in September 1829. A list of convicts sent from the ‘York’ convict hulk recommending men for a reduction in sentence includes Ashford with a note that he has broken his thigh (HO 17/40/93).

Ashford was recommended again in December 1829 but his name was crossed out, suggesting he was not pardoned this time (HO 17/73/95).

However on 31 March 1830, nearly nine years after his trip to Wickham Fair, Ashford received a full pardon. A copy of the letter from the Home Office to John Henry Capper, superintendent of convict hulks, survives in HO 13/55.

The letter does not state why Ashford was finally released, but the quarterly hulk registers in HO 8 suggest that in addition to suffering a broken thigh, Ashford’s health suffered after eight years on the ‘York’ convict hulk, noting that he had an ulcerated lung (HO 8/13).

Ashford’s experience may not be particularly extraordinary but his account of his arrest, subsequent events, and Tate’s investigations are unusual in their detail, throwing a light on how suspects were treated, and how difficult it could be to escape the suspicion of guilt.

Notes:

- 1. Ship bread was a type of inexpensive, long-lasting biscuit or cracker used as rations. ↩