Before the First World War moving between countries could be a surprisingly casual affair. There were such things as passports, but they were not compulsory, and even for those people who held one, the surviving records are disappointingly sparse. We receive lots of enquiries from people whose ancestors migrated into or out of the United Kingdom, and we often have to disappoint them because there is no record of their arrival or departure.

Some people who came and settled here went to the trouble and expense of becoming naturalised, and we have some very good records for them. Unfortunately many others did not, because they had no good reason to do so, and there was no barrier to their staying and settling without being naturalised in this period. When the subject of nationality came up in the census, some people claimed they were naturalised, but we have no record that they were. The likely explanation is that many simply misunderstood the question, but there is no way of knowing for certain. Interestingly, in the 1911 census most seem to have told the truth, because this year there was an extra question; they were asked for the year in which they became naturalised. This made it clear that there must be some kind of official process, and a request for such specific information introduces the subtle suggestion that someone might actually check.

The whole question of nationality and citizenship is unlikely to have been uppermost in the minds of very many people at all, whether they were born here or not. But then the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act, 1914 will have forced some of them to sit up and take notice, particularly in the light of war with Germany and her allies. For a long time there had been close ties between Britain and Germany, and many Germans had settled here. They now found themselves in a very uncomfortable position, including those with German-sounding names, even if their families had been settled here for generations. It is well-known that the Royal Family chose to change their name from Saxe-Coburg to the more patriotic-sounding Windsor at this time.

The act set out in detail who was British and who was not, so someone who came from Germany but was not naturalised might now risk being interned as an enemy alien. Aliens could still apply for naturalisation, but they had to fulfil a number of conditions, and there was no guarantee of success, since the act contained the ominous sentence ‘The grant of a certificate of naturalisation to any such alien shall be at the absolute discretion of the Secretary of State, and he may, with or without assigning a reason, give or withhold the certificate as he thinks most conducive to the public good, and no appeal shall lie from his decision’

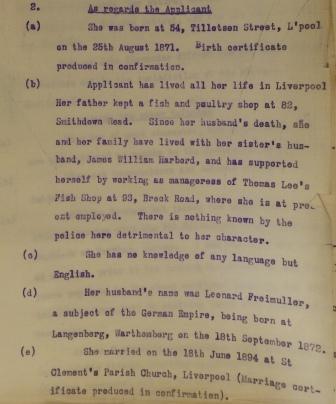

Another group affected by this act consisted of women who been married to foreign men, but were now widowed or divorced. They had acquired their husband’s nationality on marriage, and retained even after the marriage ended. I came across an example of this while I was filling in the gaps in a friend’s family tree. Mary Jane Freimuller, a widow, and her daughters were living with her sister and brother-in-law at the time of the 1911 census, and they are all listed as ‘British subject’. When the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act came into force, she will have discovered that her nationality was actually German, although her daughters were British. She married a German sailor, Leonard Freimuller, in 1894, but they had only been married for 5 years when he died.

Like many other women in her position, she had to apply for naturalisation to reclaim her status as a British national, and not an alien. Her file contains just the same kind of detail that you would find in any other application, including statements from people who knew her well, attesting to her good character, and details of her life and background. It even includes the name of the fried fish shop of which she was manageress at the time of her application in 1915.

The whole process seems to have gone smoothly in this case, and took only a few weeks, but the act made it clear that while there was likely to be no barrier in cases such as this, it was not automatic, and widows and divorced women whose husbands had been foreigners still had to apply for re-admission to British nationality. When her application was approved it was also noted that her two daughters were British subjects, under the terms of the act. The file also includes a note that she had paid the fee of 5 shillings by postal order.

You can find a number of similar cases by using the Advanced Search in Discovery using the exact phrase ‘re-admission’ and including keywords like Germany or Austria, restricting the search to series HO 144. Many of results are for women, and many of them have British-sounding forenames with German surnames. Some are also known by another surname, which may turn out to be either her maiden name, or an anglicised version of the German surname.

Neither Mary Jane nor her two daughters seem to have felt the need to change their surname at that time, although all three of them eventually married and acquired British surnames that way. Mary Jane herself was the first to do so in 1921, when she married Edward James Hughes, the lodger who lived in the same house in 1911.

Incidental details about people’s lives, such as those I found in this file are always very welcome to family historians, but best of all was something I had never expected to discover. It included the date and exact place of birth of Leonard Freimuller – 18 September 1872 in Langenberg, Warthenberg. Since he had not become naturalised himself, and never appeared in a British census I thought his origins would remain a mystery. I was wrong.

I would like to thank my fellow Family History Specialist, Mark Pearsall, for his patience in dealing with my incessant questions about nationality and citizenship.

A number of well-known and high-ranking civil servants (including Sigismund David Waley and Otto Niemeyer along with details of their their family trees are available at TNA) were asked and decided not to change their German-sounding names and even after the First World War there was the issue of women married to Aliens. It was within the power of the Home Secretary to revoke British Nationality and he did in a few cases. After the First World War the issue came to be more associated with Russians following the Russian Revolutions and thoughts of anarchy that they could have been planning in the UK at the time.

Claims for British Nationality were in most cases not permitted (for obvious reasons, but Vera Rosenberg otherwise Vera Atkins of the Special Operations Executive was an exception, she was Romanian at the time) during the Second World War leading to a large number of claims after the war and a backlog soon after. Whilst you can search in Discovery the places of birth are reflected by the political situation in Europe, e.g. Polish Russia and that when families came to the UK they did change their names to English-sounding names, e.g. Bercovitch to Bercow and the dropping of ‘vitch’ in a name seems to have been common.

This is very interesting – and I’ll tell you a bit of my related family history when it’s my turn for My Tommy’s War! My grandfather’s naturalisation papers are fascinating, though in places as unreliable as most of his other records – he regularly misdated his own birth by a year or two, though he was an educated man and far from elderly at this date. But the testimony of others, including the local police, gives a richer picture of his middle age than I can find from other sources.

Good point, Melinda, you can’t trust everything that is written down, even in an official document like this. And I agree that finding unexpected (and personal) details can be the most rewarding part of research. I look forward to reading your ‘My Tommy’s War’ post.

Fascinating. I have been trying to trace a couple who seem to have fallen into this tangle, and into the First World War. Ruby Marian Barrett was as English as you can get by ancestry; she was born in 1892. On 3rd July 1914 she married Otto von Oettingen in Folkestone; she moved with him to Germany and their daughter Zlota was born in Berlin in 1915. Otto was killed near Ypres in 1917, as was Ruby’s brother Cecil Roy Barrett. Ruby was still living in Germany in the 1960s, but Zlota had emigrated to Brazil in 1939, with German nationality – under the Act she wouldn’t have had a right to British nationality. Ruby visited Brazil twice after this, once in 1951 on a British passport, and once in 1956 on a German one.

Poor lady! Bad enough having your husband and brother fighting on opposing sides, but losing them both at Ypres must have been even worse. I wonder what life was like for her in Germany during the Second World War?

I’m sure there must be many more fascinating stories to uncover about some of the unexpected consequences of this and other Nationality Acts. I have an example in my own family, where someone was born in Germany to a British mother and an Irish (ie Republic of Ireland) father. When she tried to get a passport she found that she wasn’t automatically entitled to British nationality. The irony was that she was only born in Germany because her Irish father was serving in the British Army and had been posted there. It all ended happily, as she was able to acquire British nationality without any trouble when she applied for it.

This blog is very interesting and I note there is a mention of Russians. My grandparents arrived from Lithuania in 1913 and of course, were unable to communicate well in English. They settled in Edinburgh and their subsequent children were born there. All this soon changed, however: My grandfather, Kazimeras Papilauskas, was one of the many Lithuanians who, as a result of the War Cabinet Summary Briefing April 26 1917, Eastern Report 13 and a subsequent paper, chose to go and fight in Russia.

I have discovered that a large number of ‘Russian’ nationals failed to comply, especially in London, but in Scotland about 1100 men left their families and were transported to Russia.

Many of these men survived the fighting but found they were unable to return to Britain because they were not British nationals. Kazimeras and his cousin were perhaps more fortunate because they were in Archangel when the Slavo-British Legion was formed in 1918. They joined and served their time but I don’t think their connection with Britain was ever recognised and they continued to be described as ‘Russians’.

At the end of the Russian campaign, summer into autumn 1919, they were permitted to return to Britain. Only men who could prove they assisted the British, for example, by involvement in the Slavo-British Legion, were allowed passage. Men who could not prove this were trapped in Russia and most never saw their families again.

Documents for this part of our history possibly did not survive. I, and others, have tried to find the names of the men who went to Russia in 1917 without success. Their Alien Registration Books were duly stamped at the port of departure and on their return, they were required to report to a police station to notify the police of their address. I have no idea whether any applied for naturalisation but if anyone knows where I can find any relevant information, please get in touch with me.

I probably know the answer already, but did British men who married foreign women automatically lost their British nationality and have to reapply for it when they returned to Britain? Can’t imagine so!

My family were affected with the ailens act I believe but it was my maternal grandmother who was the foreign national. She was born beyond the Pale in Russia in 1900 to jewish parents. Her father was born in Austria, but as a rabbi, he had left there as he refused to fight in any conflict. My great grandmother was born in Poland and theirs was an arranged marriage when my great grandfathers first wife (Russian Jewish) was unable to have children. There was a huge age gap between them, but they managed to raise 6 children to adulthood. However they left Russia in 1908 because of the pogroms and settled in Constantinople (now Istanbul) where the two youngest were born.

My grandmother met my grandfather who was a geordie, serving in the Med fleet of the Royal Navy. They had their first child Rebecca in either Turkey or Malta, but I can find no record of their arrival in UK in the 1920’s. When my aunt Rebecca went to apply for a passport in her 40’s sometime in the 1960’s, and married to a British man with 7 children, she was told she didn’t exist in official records and her case had to be investigated. My grandmother by this time a widow, with grown children and grandchildren, was also investigated and both granted official papers, but how could they have been overlooked for so long? Both of them had worked, paid taxes, NI, had children and in my grandmothers case, had her own business before she claimed a pension, but neither were official??

No joined up writing in officialdom.

Wow, it’s amazing what you can find when you are just browsing sometimes. Mary Jane was my paternal great-grandmother’s sister, and my father was named after Leonard, who we are told was a lovely person. Thank you so much, Audrey, for this little bit of family history.

What surprises me is the similarity to my mother’s family. Her paternal grandmother’s family had come out to New Zealand from Germany in the first year of Canterbury’s settlement in the 1850’s, so they were well ensconced in this country by the first world war. I don’t think they had any trouble in that war, but my grandfather’s sister married her cousin, who retained the German surname, and had to report as an enemy alien every week – despite the family having lived in NZ for around 90 years by that time.

I’m exploring the incredible story of an extended family that originated in Demerara. One of odder twists is that one particularly frisky daughter appears to have been married twice in just over two months, to two German men who seem to have been cousins or half-brothers. There is evidence for a prior relationship (i.e. a baby) to explain the first wedding (which was under licence at St. Marylebone in October 1837) but nothing to explain the second one (which was by banns at St. James Clerkenwell in December 1837, and so better advertised). Today, this would look like at least one marriage of convenience for the purposes of naturalisation, but neither man’s name appears in the National Archives’ database thereof and, as this blog notes, emigration was much more casual in the the early 19thC. Was there any legal advantage in marriage to a British subject to explain why the bride would take the risk of committing bigamy? My darkest thought is that the second marriage is a set-up to bilk the second groom in some way, but that would be another story.