In part one and part two of this blog series I’ve been tracing the history of the ‘real’ Geoffrey Chaucer – the man behind the Canterbury Tales – as he worked his way through the medieval civil service as soldier, diplomat, accountant, customs official and royal builder.

In this third and final blog in the series, I’m going to look at Chaucer’s connections with the heart of government, Westminster, where his tomb still stands today in Westminster Abbey. Throughout his accounting career, Westminster – as the home of the Exchequer – was an important location for financial transactions, but it also touched his life in other ways: as the home of Parliament, in which he would serve as an MP, as the home of the English common law courts, in which he occasionally found himself, or as the location of his tomb. Chaucer’s links with Westminster lasted throughout his life.

Chaucer and Parliament

Perhaps Chaucer’s best-known connection with Westminster is the time he spent as a Member of Parliament in the so-called ‘Wonderful Parliament’ of 1386 1.

![Chaucer returned as one of two Knights of the Shire for Kent in 1386 [catalogue reference: C 219/9/1]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151403/20170922_091501.jpg)

Chaucer returned as one of two Knights of the Shire for Kent in 1386. Catalogue ref: C 219/9/1

![Alongside William Betenham, his fellow MP for Kent, Chaucer claimed £24 9s for his parliamentary expenses for 61 days during the 'Wonderful Parliament' of 1386 [catalogue reference: C 54/227 m. 16d]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151401/Parliament-expenses.jpg)

Alongside William Betenham, his fellow MP for Kent, Chaucer claimed £24 9s for his parliamentary expenses for 61 days during the ‘Wonderful Parliament’ of 1386. Catalogue ref: C 54/227 m. 16d

As an MP, Chaucer made the most of his time at Westminster outside of parliamentary proceedings: collecting annuities from the Exchequer; conducting business in his capacity as controller of customs (which he would soon give up); giving evidence in the refectory in the Scrope-Grosvenor chivalry case (as discussed in part one of this blog series and in another of our recent blogs); and taking part in legal proceedings at the home of English common law, Westminster Hall.

Chaucer and the law

It is in the records of the central common law courts that we find some of the lesser-known documents about Chaucer and his career. The poet’s connection with the legal system is not entirely certain; many scholars have argued that Chaucer may have received some sort of legal training, but no documentary evidence has yet been found to verify or dismiss this claim. The evidence we do have, however, does show a level of interaction, with legal records naming Chaucer as defendant, plaintiff and surety on multiple occasions. The collection of medieval legal records held by The National Archives is vast, and can be difficult to navigate at first, but the material found within can help to shed new light on medieval society – even on such famous figures as Chaucer. They can also make us reconsider these figures.

![Close Roll enrolment releasing Chaucer from all actions concerning the 'raptus' of Cecily Chaumpaigne on 1 May 1380 [catalogue reference: C 54/219 m. 9d]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151334/Champaigne.jpg)

Close Roll enrolment releasing Chaucer from all actions concerning the ‘raptus’ of Cecily Chaumpaigne on 1 May 1380. Catalogue ref: C 54/219 m. 9d

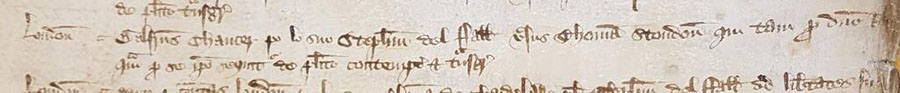

Chaucer appoints an attorney to answer a plea of trespass and contempt by Thomas Stondon. Catalogue ref: KB 27/475 attorney rot

Chaucer appoints an attorney to answer a plea of trespass and contempt by Thomas Stondon. Catalogue ref: KB 27/475 attorney rotChaucer appoints an attorney to answer a plea of trespass and contempt by Thomas Stondon. Catalogue ref: KB 27/475 attorney rotChaucer appears to have been good at settling legal proceedings outside of formal court proceedings, which can make it difficult to trace his movements. In 1379, for example, he was called to answer Thomas Stondon in the Court of King’s Bench on a plea of ‘contempt and trespass’, and was recorded appointing an attorney, but no further proceedings of this case can be found, suggesting that the case was settled before it came to court.

![Debt case in the Court of Common Pleas by an innkeeper, Henry Atte Wode against Chaucer (and others) for a debt of £7 13s 4d [catalogue reference: CP 40/511 rot. 490d]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/29155548/chaucer_3_2.jpg)

Debt case in the Court of Common Pleas by an innkeeper, Henry Atte Wode against Chaucer (and others) for a debt of £7 13s 4d. Catalogue ref: CP 40/511 rot. 490d

![Chaucer acting as surety for the appearance of Matilda Nemeg accused of leaving her service to Maria Alconbury without licence (Chaucer's name can be seen in the bottom right of the document, six lines from the bottom) [catalogue reference: CP 40/511 rot. 531]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151355/Nutmeg.jpg)

Chaucer acting as surety for the appearance of Matilda Nemeg accused of leaving her service to Maria Alconbury without licence (Chaucer’s name can be seen in the bottom right of the document, six lines from the bottom). Catalogue ref: CP 40/511 rot. 531

![Writ enrolled in Exchequer memoranda roll in January 1391, discharging Chaucer from the repayment of £20, stolen by thieves near 'Le Fowle O[a]k' in the previous September [catalogue reference: E 159/167]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151336/Fowle-Oak-E-159.jpg)

Writ enrolled in Exchequer memoranda roll in January 1391, discharging Chaucer from the repayment of £20, stolen by thieves near ‘Le Fowle O[a]k’ in the previous September. Catalogue ref: E 159/167

![Confession of Richard Brierly April 1391 of having (with other) robbed Chaucer in the previous year [catalogue reference: KB 29/37 rot. 22d]](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01151404/20170928_144001.jpg)

Confession of Richard Brierly April 1391 of having (with other) robbed Chaucer in the previous year. Catalogue ref: KB 29/37 rot. 22d

In 1399, Chaucer moved from Kent back to Westminster, where he leased a tenement in the garden of the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey until his death, probably in the next year. The traditional date of his death, 25 October 1400, is based on a now illegible inscription on his tomb in Westminster Abbey, as recorded by the antiquarian John Stow (although the tomb now standing in Westminster was not erected until 1556). Westminster, the heart of government and the Civil Service now, had been a major part of Chaucer’s life and career, and it seems a fitting location for his burial and later tomb.

Throughout these blog posts, I’ve tried to show that Chaucer – while a great poet and lasting English legacy – was also a real person, who walked the streets of London and Kent, and worked hard at his day job before retiring home to his other writings in the evening. His experiences of the people he met, the situations in which he found himself, and the everyday life he saw on the streets may well have influenced his writing; by digging a bit deeper, we can start to see more of the ‘real’ Chaucer.

The Chaucer Heritage Trust is currently running a competition for aspiring Chaucer scholars and writers. If you know someone under the age of 19 who might be interested in taking part, the competition runs until 31 January 2018.

Further reading

The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson (Oxford, 2008)

Chaucer Life-Records, ed. Martin M. Crow and Clair C. Olsen (Oxford, 1966)

Notes:

- For more on the ‘Wonderful Parliament’ and a more general history of Parliament in this period, see The History of Parliament’s website. ↩

- Further details about these payments can be found in Chaucer Life-Records ed. Martin M. Crow and Clair C. Olsen (Oxford, 1966), pp. 367-8. ↩

- For some background to this case see Ibid., pp. 345-7. Chaucer’s father John had been abducted as a child, which led to formal legal action, but in the Chaumpaigne case no formal proceedings were filed, making it difficult to contextualise, but it is perhaps telling that those witnessing the release, men such as John Philipott, were men within Chaucer’s professional circle. ↩

- Catalogue ref: CP 40/511 rot. 333. ↩

- The full story can be found in Chaucer Life-Records ed. Martin M. Crow and Clair C. Olsen (Oxford, 1966) pp. 478-489. ↩