Burgess and Maclean. The names have been etched into postwar Britain history, synonymous with espionage, intrigue and scandal.

The files released today at The National Archives show for the very first time the inside story on the investigation into these men, and reveal fascinating insights into who they were, why they betrayed their country and how they remained undetected for so long.

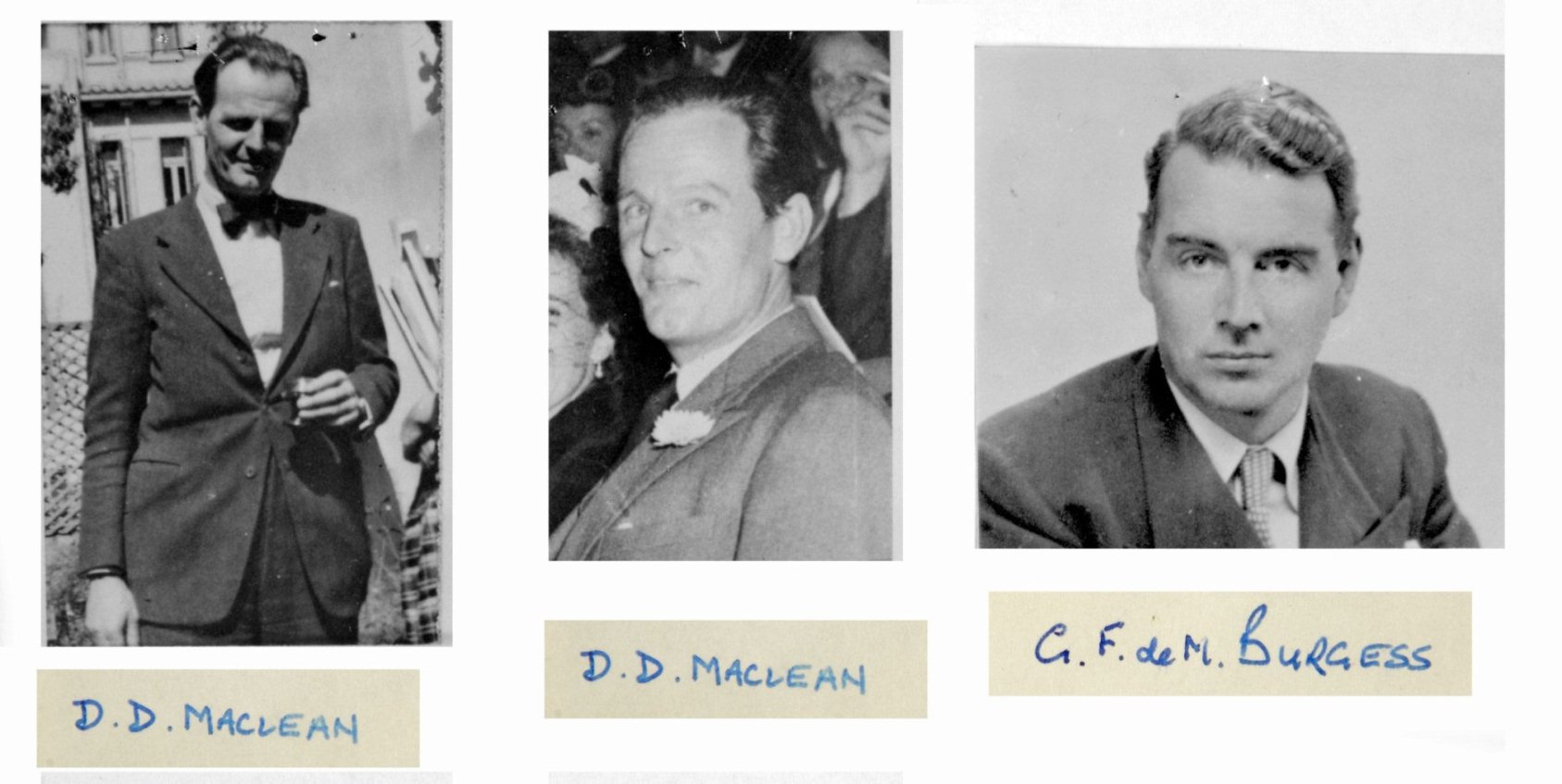

The story began at the rather innocuously named Cambridge University Socialist Society, where Harold ‘Kim’ Philby was elected Junior Treasurer on 9 March 1932. It was here that Philby met fellow travellers Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess. Two years later Philby was recruited by the Soviet intelligence officer Arnold Deutsch and proceeded to supply Deutsch with further candidates for recruitment, among them Maclean and Burgess. From these humble beginnings the legendary Cambridge Five spy ring was born.

After leaving Cambridge, both Burgess and Maclean disassociated themselves with their communist past and quickly built careers at the heart of the British establishment. Maclean passed the Foreign Office exam with flying colours and was thought to be one of the most promising young diplomats throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Burgess had a more colourful career, working for a right-wing MP, the Secret Operations Executive (SOE), and the BBC before also ending up in the Foreign Office. For almost two decades these men moved unsuspected in the highest circles of the British diplomatic and intelligence world, while at the same time feeding back thousands of pages of top secret documents to their handlers in Moscow.

The files released today give a good idea of how they managed this extraordinary feat. Interviews with friends and colleagues after Burgess and Maclean’s defection in 1951 provide accounts of two very different men, but no one suspected either of being a Soviet spy. Maclean was in many ways the archetypal career diplomat, and in 1938 a senior figure observed on his appointment to the British Embassy in France that, ‘He is a very nice individual indeed and has plenty of brains and keenness. He is, too, nice looking and ought, we thinking to be a success in Paris from the social as well as the work point of view’. A friend noted even after Maclean’s defection that they did not believe he could be a communist spy and instead viewed him as a ‘wooly Liberal’ (FCO 158/186).

Burgess was a very different character and the files give considerable insight into his career, including his time working for SOE and his recruitment as an MI6 agent by none other than Anthony Blunt, another of the Cambridge Five (KV 2/4101). The files paint a rather mixed picture of Burgess, perhaps summed up best by senior Foreign Office figure Gladwyn Jebb’s comment that ‘my general impression was that Burgess was undoubtedly brilliant, and indeed attractive, but he gave me, I confess, a most uneasy feeling’ (FCO 158/182).

Living double lives clearly took its toll, and the period before their defections saw major indiscretions from both Burgess and Maclean. In autumn 1949 Burgess visited Gibraltar and Tangiers. His behaviour prompted the Defence Security Officer, Gibraltar to complain to MI5. He apparently had openly discussed highly sensitive information about MI5 and MI6 with strangers and acted in a generally indiscreet manner. In addition the DSO noted that ‘Burgess appears to be a complete alcoholic and I do not think that even in Gibraltar have I seen anyone put away so much hard liquor in so short a time.’ Other aspects of his lifestyle also caused concern, particularly his ‘unnatural proclivities’ or homosexuality (KV 2/4101). Unsurprisingly Burgess’ behaviour led to him being severely sanctioned by the Foreign Office, but he avoided being fired. Instead he was sent to Washington in what was considered a relatively minor post. On his departure, Burgess told George Middleton, Head of Personnel at the Foreign Office, that he was ‘a “left-wing socialist”’. Middleton commented that ‘I reminded Mr Burgess that civil servants and more particularly foreign servants were expected to be a-political and it would be a grave mistake to deviate from that rule’. In hindsight it is obvious that more drastic action should have been taken (FCO 158/182).

Maclean also suffered from living this double life. In 1948 he was appointed to a senior post at Cairo but rapidly fell in with the ‘fast set’ and started drinking heavily. He was involved in a number of incidents which culminated in breaking into the flat of a female member of the US Embassy and trashing it. He was sent home and had a period of rest and recuperation and appeared to make a full recovery. There were, however, signs that he was still struggling. In January 1951 a Foreign Office official noted that he had been at a party where ‘Donald Maclean, stung by some very silly comments of the ex-Communist, said “of course you know I am a Party Member, have been for years!” Obviously this is not to be taken seriously, but it is evidence that D is still hitting it up and that he is apt to be impossible in his cups’ (FCO 158/186).

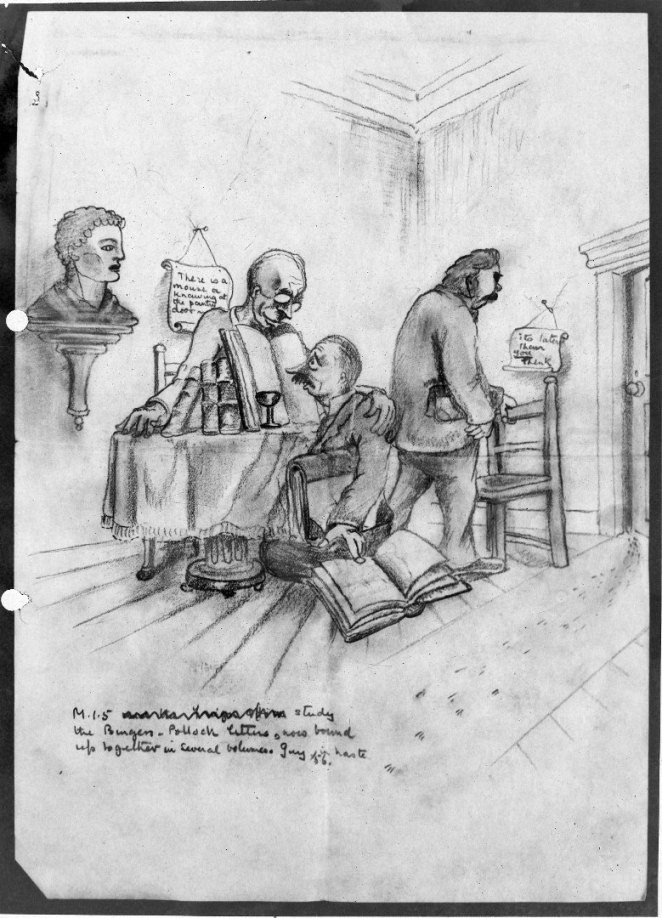

Despite these outbursts no one suspected either Burgess or Maclean of being a Soviet spy until decrypts of secret Soviet signals pointed the finger at Maclean in April 1951. Philby warned Maclean of the imminent danger and he fled, with Burgess, to the Soviet Union. The files released today contain detailed reports and intercepted correspondence which provide fascinating new insight into Burgess and Maclean’s lives after their defection. Burgess in particular wrote a number of colourful letters home which initially painted a very positive picture of life in Moscow, but later suggest that he was increasingly homesick. Accompanying these are a number of sketches, including one wonderful image in which Burgess mocks the MI5 agents who he knew would be reading through his correspondence.

These files also reveal interesting sub-plots to the main drama that was Burgess and Maclean’s disappearance. Unsuspecting of her knowledge of her husband’s activities, the Foreign Office continued to provide support for Melinda Maclean and her family, liaising with her on a move to Switzerland. Melinda and her children too disappeared, later joining Donald in Moscow. Maclean’s brother, Alan, was cleared of any involvement, but resigned from the Foreign Office (going on to pursue a successful career in publishing).

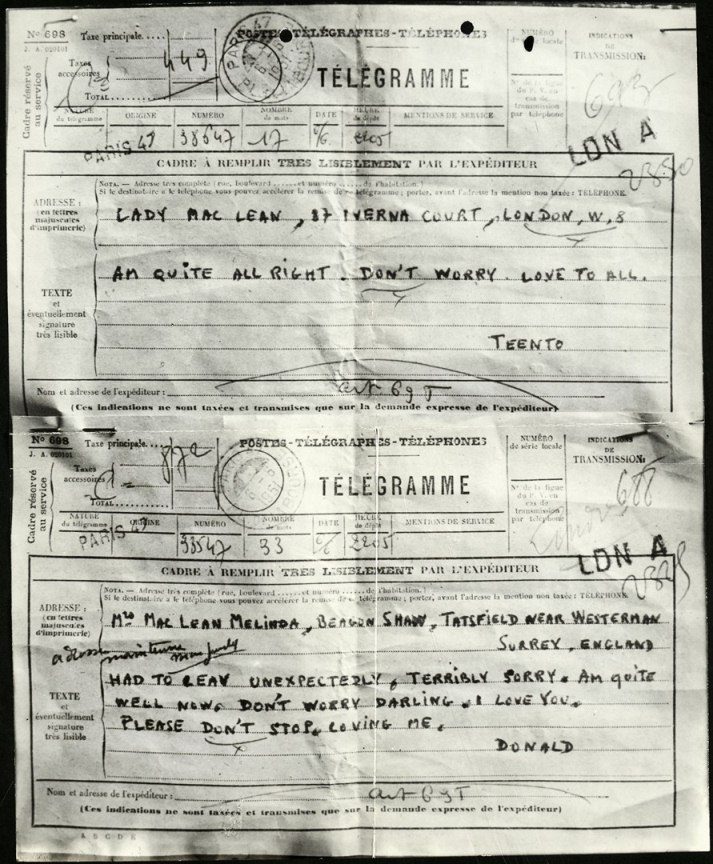

Donald Maclean’s telegrams home (catalogue reference: KV 2/4142)

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the CIA was concerned at the possible extent to which British intelligence had been compromised. The closeness of Philby to both Burgess and the CIA caused particular alarm. As a means of restoring confidence, the British sought to inform the Director of Central Intelligence, General Walter Bedell Smith, of the main facts of the Maclean case. Ironically, they wished to highlight ‘the role which Kim Philby himself played during the very delicate investigations’. Such a move entailed revealing information on the top secret VENONA project, which provided decrypts of Soviet communications, and encountered opposition from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. When Bedell Smith was eventually briefed, he graciously commented that ‘Of course [MI5 Director General] Percy Sillitoe lied to me like a trooper but I appreciate he had to do it on account of your understandings with Hoover and it was not his fault’ (FCO 158/21).

Put together, the newly released documents enable us to fully understand the Burgess and Maclean story for the first time and reinforce why this was one of the greatest scandals of post war British history.

We know from previously released files (T 231/1145) that from 1956 Guy Burgess had been in correspondence with the Bank of England and that a “private” letter was sent by Burgess to Peter Thorneycroft (Chancellor of the Exchequer) starting “My dear Peter” complaining about Treasury vetting of payments from his account. Burgess’ letter was considered to be a request for emigration treatment of his bank account and that Burgess was thought to have had no more than £5,000 in assets. There was no objection to a non-resident account. There was a view that the Section 40 directions were useful to “the cloak and dagger boys” who would find it useful to know whom he was paying and whom was paying him. Thorneycroft agreed to the deal.

“Despite these outbursts no one suspected either Burgess or Maclean of being a Soviet spy until decrypts of secret Soviet signals pointed the finger at Maclean in April 1951”

See, please, Guy Liddell’s Diaries: “I then told him (Barty Bouverie) that for some years -in fact since the beginning of the war- we had been looking for someone in Foreign Office circles who had been leaking to the Russians, and that considerable suspicion rested on Donald Maclean. It was important to establish whether on certain dates which I did not give, he had been in fact in Washington” (kv/4/473, 18th May 1951)

Quite a different story.

Not at all. The decrypts id-ed someone from the British Embassy as a Soviet spy. On certain days he had been in New York to meet his contact. Melinda Maclean was pregnant at the time and staying with her mother in New York. Maclean had been in New York on the days in question.

[…] Burgess and Maclean. The names have been etched into postwar Britain history, synonymous with espionage, intrigue and scandal. The files released today at The National Archives show for the very… Go to Source […]

We have removed comments that did not comply with our participation guidelines for this blog:

• Be respectful of others

• Do not use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative

If you have a query about why your comment has been removed, please contact us at blog@nationalarchives.gov.uk

You can read our full participation guidelines and moderation policy here: http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/moderation-policy/

[…] Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean (catalogue reference: FCO 158/6). National Archives. […]

[…] http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/burgess-maclean-revelations/ […]

These releases never seem to stray into shall we say nuclear territory. One of the main reasons as far as I can make out why Maclean was so significant is that he had the job of liasing with the USA as to what nuclear secrets could be declassified. Obviously for such a job he must have been indoctrinated into the whole works. Perhaps not totally coincidental was home was in the vicinity of the nuclear establishment Fort Halstead Kent. (It was said he was quite strict on declassification!) With Philby we still haven’t heard exactly what he was doing immediately postwar. In his memoir he’s in Hitlers bunker soon after the defeat. I suspect nuclear matters may explain and being speculative I suspect he was part of the British contingent of the ALSOS mission. Would explain why other members were never keen to discuss their involvement. Previous releases have confirmed the common denominator of Edith Tudor Hart in nuclear espionage. She was embroiled romantically with Broda who was on the nuclear TAP project, and alongside Broada was Nunn May who was exposed. And of course as we seemingly know she helped to recruit Philby in the first instance.

Very interesting. I wonder if some of the British embassy and consulates members in Spain During ww2 and after were not suspected of being spies.

I am thinking of Donald Darling,Creswell and Rupert Henry Beaumont.

I understand they had sympathy for the Spanish Republicans which might have led British authorities to suspect them

Is there a record of where Donald Maclean lived (e.g. address) when posted to Washington DC?

No comment on why Burgess and McLean were allowed to escape. Burgess was not suspected, but McLean was, so why was watching of McLean not 100%? Why was he never watched at weekends? Watching was, frankly, very poor. They should never have escaped.