Aerial photograph of the Beckton Gasworks in London on 7 September 1940; three German bombers are visible (catalogue reference: AIR 34/734)

Air raids were one of the main strategies employed during the Second World War by both Nazi Germany and the allied forces. On 7 September 1940, 75 years ago today, the first night of what would become one of the most devastating continuous nighttime aerial bombing raids over London, known as the Blitz, began.

Derived from the word ‘Blitzkrieg’, meaning lightning war, the Blitz saw the sustained, targeted bombing of civilians by Nazi Germany. Between September 1940 and May 1941 the German Luftwaffe attacked the city on over 70 separate occasions, with around 1 million homes being destroyed and killing over 20,000 civilians.

Beginning of the London Blitz

The aim of these air raids was to cause death and destruction. Damaging the infrastructure of a city would in turn reduce the city’s ability to support the country’s war effort, and the raids which began on 7 September 1940 were no exception. Earlier, during the day, a raid of 350 German bombers advanced up the Thames estuary, targeting the docks. [ref] 1. A. Price, Blitz on Britain 1939-45, (Stroud, 2009) [/ref]

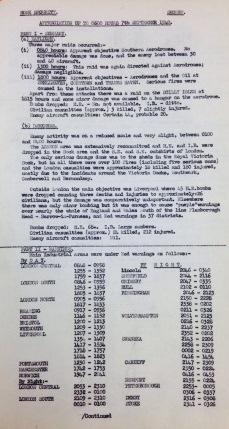

Daily Report of the Ministry of Home Security for 7 September 1940 (catalogue reference: HO 202/1)

As the daytime raid ended it gave way to a heavy night attack, which, unbeknown to Londoners at the time, would set the precedent for the nights to come over the next two months. Over 300 bombers attacked the city from all directions, using the fires from the earlier daytime attack to locate their targets. The attack continued from 20:00 on 7 September to 04:30 the following morning, by which time over 400 Londoners had been killed and a further 1,600 injured.[ref] 2. A. Price, Blitz on Britain 1939-45, (Stroud, 2009) [/ref]

The daily reports of the Ministry of Home Security at the time suggest little awareness of the sustained aerial attacks that were to come. Conclusions from the night state, ‘the present degree of effort at night suggests that the main object is training and the secondary object damage and disturbance, rather than serious attempts at destructive bombing’. The report continues, ‘this [bombing] has not yet been carried out at night on anything approaching the scale of the R.A.F. [Royal Air Force] bombing in Germany or the full potential of the G.A.F. [German Air Force]’.[ref]3. HO 202/1 [/ref]

Devastation at the docks

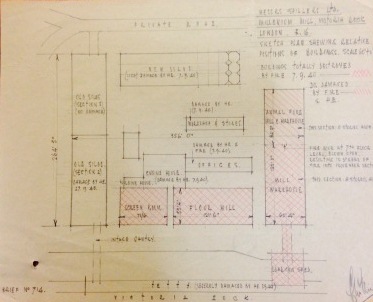

The primary targets of the bombers were the dockland areas of London. One company directly affected as a result of enemy bombing was Messers Spillers Ltd’s Millennium Mill at Victoria Docks. A large number of high explosive bombs were dropped on the mill at 17:40 on 7 September. Fires immediately broke out which then spread to other parts of the mill.

Mr W Brown, a fire watcher stationed on the premises at the time, described how the Screen Room was hit by a high explosive bomb and caught fire immediately. The Turbine House and Engine Room were also put out of action which caused a failure of the sprinkler system throughout the mill. The fires were not fully extinguished until 3-4 days after the incident, with the result that the Screen Room, Flour Mill, Loading Shed and Warehouse were all completely destroyed.[ref]4. HO 192/358 [/ref]

Plan of the damage to Millennium Mill (catalogue reference: HO 192/358)

Another dock attacked was the Royal Albert Dock, where HM Trawler Abronia was sunk after the crane next to it received a direct hit and collapsed onto it. Seven Royal Navy ratings who were sheltering under the same crane at the time lost their lives. In the grim reality of wartime, they were buried in communal grave number 1 at East London cemetery, along with civilians killed in the same raid.[ref]5. ADM 358/2981 [/ref]

Bravery in the face of adversity

Another area which suffered greatly on this night was Woolwich, and in particular the Royal Arsenal. Extensive fires broke out and many of those involved in combating them were recommended for gallantry awards.

One such person was a fireman named Samuel Frederick Pritchard, who was praised for his leadership and devotion to the fires on the night of the 7 September. On that night Pritchard was often single-handedly in charge of fires, with only the aid of auxiliaries, who often had little or no training. His leadership was commended, ‘owing to the continued bombing of the site, which caused numerous casualties, some of the men began to waver, but, by excellent leadership, Pritchard rallied them’. Significantly he prevented the fire from spreading to other buildings which contained explosives.[ref]6. HO 250/53/1822 [/ref]

The nights and weeks to come

Fire fighters spent most of 8 September trying to control the blazes from the previous night, in an effort to prevent the fires becoming beacons for possible subsequent attacks. However, the fires proved too numerous. Many were still raging by the time night fell and the bombers returned to resume their attack.

The daily report of 8 September reads a little differently to that of the previous day, stating ‘further bombing on a large scale, probably directed at ports, must be expected’. The report also recommended that fire services should be at full strength in an effort to combat large fires more effectively and reduce the extent to which they aided enemy raids.[ref]7. HO 202/1 [/ref]

Weekly reports on bombing across the country, again produced by the Ministry of Home Security, highlight the increased intensity of raids on London. Report number 12 for 4-11 September concluded ‘the policy of attacking aerodromes primarily with the object of attempting to gain air superiority has been replaced by a concentrated bombardment of London with the apparent object of crippling the docks and dislocating railway communication’.[ref]8. HO 202/8[/ref]

- First page from the weekly report of 4-11 September 1940 (catalogue reference: HO 202/8)

- One of the pages listing the records destroyed at Arnside Street (catalogue reference: WO 32/21769)

- Recommendation of Samuel Frederick Pritchard for a Gallantry Award (Catalogue reference: HO 250/53/1822)

As well as damage to infrastructure, other institutions also suffered. On 8 September the Army Records Centre at Arnside Street in Southwark was hit, resulting in the destruction of many records, including volunteer records and photographic plates from the First World War, as well as numerous Boer War records and volumes of London newspapers from the War Office library.[ref]9. WO 32/21769 [/ref]

Researching the Blitz

As the Blitz progressed, the Ministry of Home Security began to record where bombs fell to analyse any patterns in the raids and enable them to best coordinate a response. This became known as the Bomb Census. You may have heard of the Bomb Sight website, which allows people to locate where bombs fell in London between 7 October 1940 and 6 June 1941; it is partly based on selected Bomb Census maps held here at The National Archives. The website also maps the first night of the Blitz.

The National Archives holds many records relating to Second World War bombing, including the London Blitz, but this is not always an easy topic to research. Our research guide on the Bomb Census survey and related records will introduce you to other sources related to the bombings and guide you through the research process.

[…] The beginning of the London Blitz […]

Hello my name is Gary Jeffrey and I’m trying to find a article about my uncle that lived on Morland Ave. in Dartford during the end of the second world war . There home was destroyed and my uncle was just a baby and the home guard couldn’t find him in amongst the rubble except for a neighbour that searched and found him under a billiards table . The man was Keith Richards uncle his name was Reg Foster there was a news paper clipping and the clipping read miracle baby Graham Jeffrey found under rubble by Reg Foster and i believe the paper was the Dartford Times .I have seen the clipping but unfortunately it has been misplaced so my question to you is can you suggest or help me find this clipping in the archives . Thank you sincerely Gary Jeffrey British Columbia Canada

Hi Gary,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

My Mum worked at Peek Freans and during the Blitz she used to have to go up on the roof of that building to do firewatching. It must have been very frightening. In later years I actually had the opportunity to go up there and the view is a vast expanse of the Thames. She must have seen much devastation. When there was an air raid, all the accounts books had to be stowed in a large safe, into which she & other employees also went for safety.

My Great Uncle was on HMS Abriona and lost his life on 7th September 1940. I assume he could have been one of the ones sheltering under the crane. Would the records about this at Kew confirm this?

As it was 80 years ago this week I have been looking for information online and reviewing the records I have. I have the original telegram to my great garndparents saying he had been killed and many letters with information as they were trying to find out exactly what had happened. There is one letter dated 24th September 1940 from a family friend who was in Deptford at the time, who took on the task of finding out what had happened. It is a graphic letter explaining what he had found out , following visits to East London Cemetery, speaking to the mortuary keeper at West Ham baths, and Royal Albert Dock police. Although very sad, it is a precious piece of history, and I have often wondered whether it would be of interest to others. If it might be I would be grateful for some advice as to whom I might share it with.

My parents were married on this day 80 years ago. They spent their first night in a hotel on the Strand and my mother recalled seeing bouncing bombs down the Strand.

Thank you for preserving this material and making it available. Your mention of the fire watchers brings back many memories. My mother was one of those volunteers. She had two jobs, a day-job at a printing firm, putting gold leaf illustration onto bibles, and at night, working as a Fire Watcher. On a roof top, watching where bombs were falling, never knowing if the next bomb would fall on you. But just like so many people, going back for more ever night. Just one of the “silent majority” that kept calm and carried on.

Excellent article.

Those interested in the Blitz might wish to consult my book The First Day of the Blitz (Yale University Press, 2007) Also I wrote about the Blitz in my and William Abrahams’ London’s Burning (Constable, 1994) Best, Peter Stansky

I was born on 4the September 1939 in Kent near London. I remember being rushed hear and there with my mother.

My parents were married on that day in Harrow. My father’s 3 weeks army leave was cancelled and their planned honeymoon became a long weekend. At the reception in my grandmother’s garden they could see the glow in the sky from the docks on fire on the other side of London. Some of the wedding guests stayed in the tube overnight. What a day to have married!

Hello Helen,

It may be that this is old news but it may be useful for others.

Imperial War Museums could be a suitable place to offer your documents to.

Despite its name the museums – there are now five – are social history museums.

In order to see if the items are suitable there’s a strict procedure to be followed. This involves an initial online form.

In the first instance, please see the dedicated page on IWM’s

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/managing/offer-material

However because of the current COVID restrictions, this service is currently suspended.

In any event – even when restrictions are lifted – please DO NOT take your documents to the museum until a definite appointment has been made. Staff and volunteers are unable to accept items.

This is because they could become lost or damaged in transit between departments or may not be suitable for IWM’s collection.

That’s why IWM routes everything through the online contact.

I hope this helps.

I was nearly five years old . I clearly remember standing outside our house in Cann Hall road, Leytonstone, seeing the huge fleet of aircraft proceeding steadily overhead. They were not very high, the afternoon sun gleaming on the transparent cockpits. The front planes were, I have learnt, likely the Dornier type, bubble nose cockpit where, I think, the figure of the pilot could just be made out.To the best of my memory there was no visible attack by our planes taking place. I don`t think there were any barrage balloons up either, as the German force kept close square formations across the whole sky, staying at one level, all at the same height.The fleet made a leisurely curve over Temple Mills railway marshalling yards, the mass of planes turning slowly without `banking` By then they had begun to go behind the horizon of the Stratford & East Ham district.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.