Philae. The Pearl of Egypt. Not exactly my favourite temple complex, but still quite something. It is actually so striking that it almost doesn’t matter that the ancient (Egyptian, Graeco-Roman and Christian) buildings are not standing on the actual island of Philae, which is buried under the clear waters of Lake Nasser, but on the island of Agilkia, some 300m downstream.

The rescue of the temples of Philae in the 1970s is fairly well documented; less well known is the fact that it all began in the 1890s and that Philae, almost doomed, had to be saved over and over again!

Herodotus once described Egypt as ‘a gift from the Nile’; it used to be. Every year, floods would guarantee good crops or ruin them. If it was too high, it would drown everything; if it was too low, nothing would grow. In 1894, the British Administration in Egypt, wishing to improve agriculture and irrigation, decided to build a dam on the first cataract of the Nile, not far from Aswan, in the south of the country. This, they hoped, would enable them to control the floods and ensure that water would always be available.

When the scheme was announced, several learned societies, notably the Society for the Preservation of Monuments of Ancient Egypt (SPMAE) and the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the Egypt Exploration Society), expressed concerns. They knew that the island of Philae would be partially or even totally submerged when the reservoir was formed. They warned that water would destroy the extremely colourful decorative paintings and that ‘in a few years, the whole group of buildings would be virtually destroyed’. In February 1894 the SPMAE and the Society of Antiquaries passed resolutions ‘to prevent [Britain] being in any way responsible for what would certainly be considered an act of vandalism’ (FO 371/5384).

SPMAE to Kimberley, 7 March 1894 (catalogue reference: FO 78/5384)

Lord Cromer, the British Agent and Consul General in Egypt, was very aware of the importance of archaeology, but he thought the modernisation of the system should take precedence. He decided, however, to refer the matter to a technical commission, tasked with examining available options. They were not supposed to pay any attention to the monuments, but Philae was difficult to ignore.

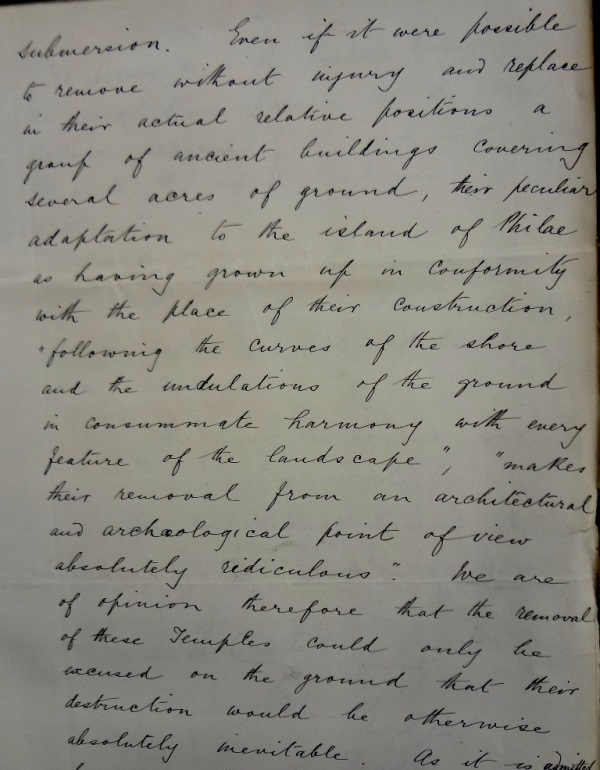

William Garstin, from the Ministry of Public Works, suggested the temples could be either raised or moved to the neighbouring island of Bigeh. The latter, in particular, caused much incredulity among the members of the SPMAE who found the idea ‘ridiculous’. On 7 March 1894, they wrote to Lord Kimberly, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs:

‘such a removal would in the eyes of our society be equally as fatal to this remarkable group of temples as its annual submersion’.

T H Sanderson, the Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs commented: ‘if it turns out that the Assouan [Aswan] site is really the best, I am afraid that archaeological and aesthetic considerations must give way.’ (FO 371/5384)

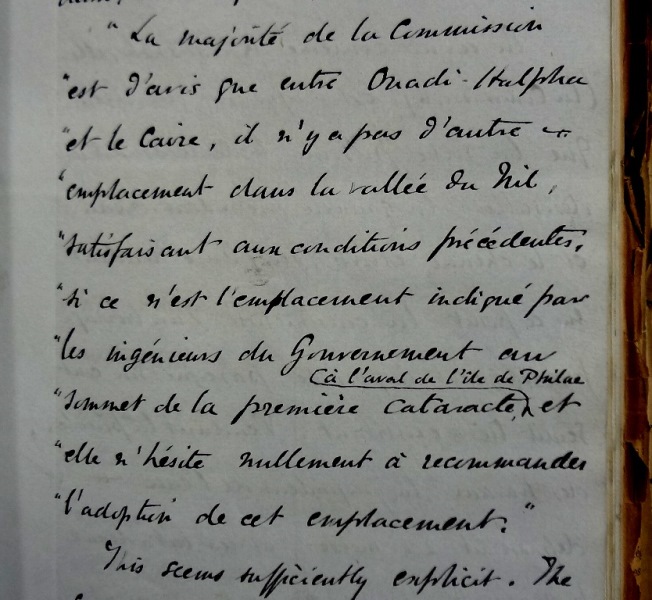

The technical Commission was formed in February 1894. Composed of three engineers from Britain, France and Italy, it soon rejected other possible sites and confirmed that Aswan was the best possible location for a dam. In May, Garstin forwarded the Commission’s full report; his conclusion was rather blunt: ‘if the damn be made at Assuan [Aswan], the temple must either be raised, removed or submerged’.

Extract from the Technical Commission’s report (catalogue reference: FO 78/5384)

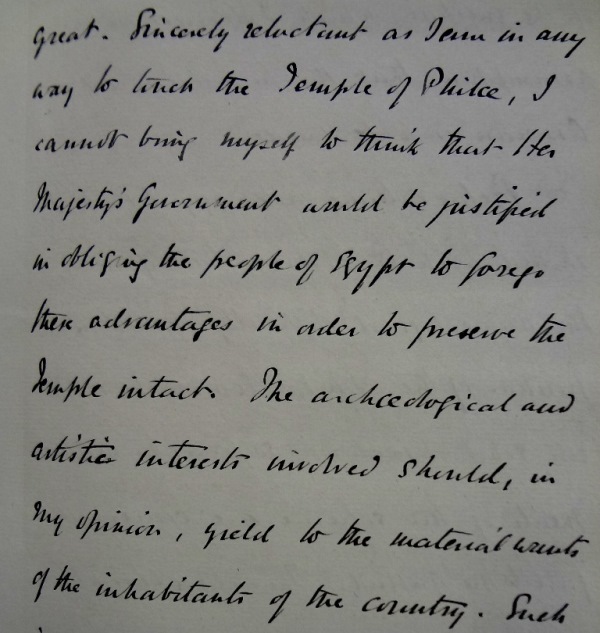

Lord Cromer agreed and wrote to Lord Kimberley in June: ‘the archaeological and artistic interests involved should, in my opinion, yield to the material wants of the inhabitants of the country.’

Cromer to Kimberley, 26 June 1894 (catalogue reference: FO 78/5384)

Philae seemed to be doomed. Lord Cromer, however, wasn’t totally impervious to the charms of Ancient Egypt. In 1895, Captain Henry Lyons, of the Royal Engineers, described as ‘a distinguished Egyptologist’, started surveying the island and examining the substructures and foundations (FO 78/4761). The excavation work was completed in April 1896, and ‘the foundation masonry was found to be in a sound condition’ as well as very deep, so Lyons thought the temples could survive submersion provided all masonry was underpinned (FO 78/4762). Construction started in 1897, and the dam was completed in 1902.

On 1 November 1902, a Mr Watt from Glasgow wrote to the Foreign Office, claiming he had invented a new kind of coffer dam which could be built around the temples and save them from destruction (FO 78/5384). Cromer commented, rather curtly:

‘Mr J. M. Watt is in error in supposing that the temples of Philae will be gradually destroyed on the opening of the dam at Assouan (…). The Egyptian government do not propose to avail themselves of his offer to construct a coffer dam round the island’ (FO 141/367).

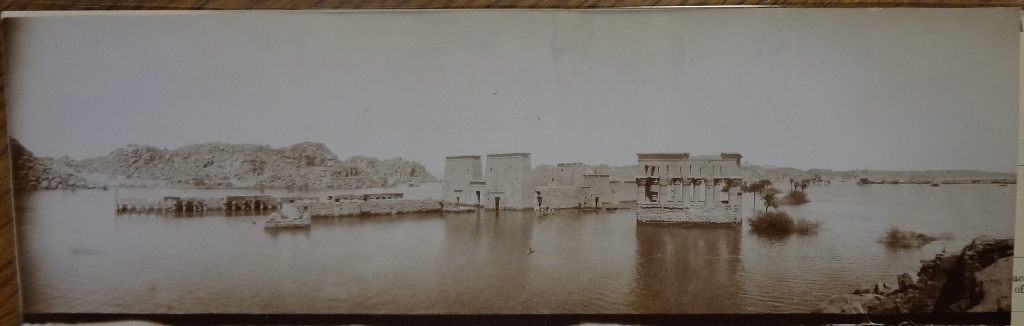

Philae in 1903 (catalogue reference: COPY 1/467/144)

The Philae problem was raised every time the dam had to be heightened. In 1932, in particular, the Egyptian government looked at various options to protect the temples. They turned to the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, as they had heard about new technologies which had been used on St Paul’s Cathedral. Barnett, the director of the Building Research Station replied somewhat sheepishly that he was anxious to help but that it wasn’t ‘immediately apparent in what manner this process could be used to waterproof masonry, of the type usually erected by the ancient Egyptians’ (DSIR 4/2520).

From 1932, Philae was almost entirely submerged for most of the year; the bright paintings washed away and the vegetation destroyed, but the buildings were still mostly intact.

- Philae in 1931 (catalogue reference: OS 1/384)

- Philae in 1934 (catalogue reference: OS 1/384)

In 1958, however, Egypt (or, as it was then called, the United Arab Republic) made hydroelectricity a priority and needed a new dam. The Aswan High Dam would create a huge artificial lake (Lake Nasser) and it was clear that Philae, along with other archaeological monuments, would be lost.

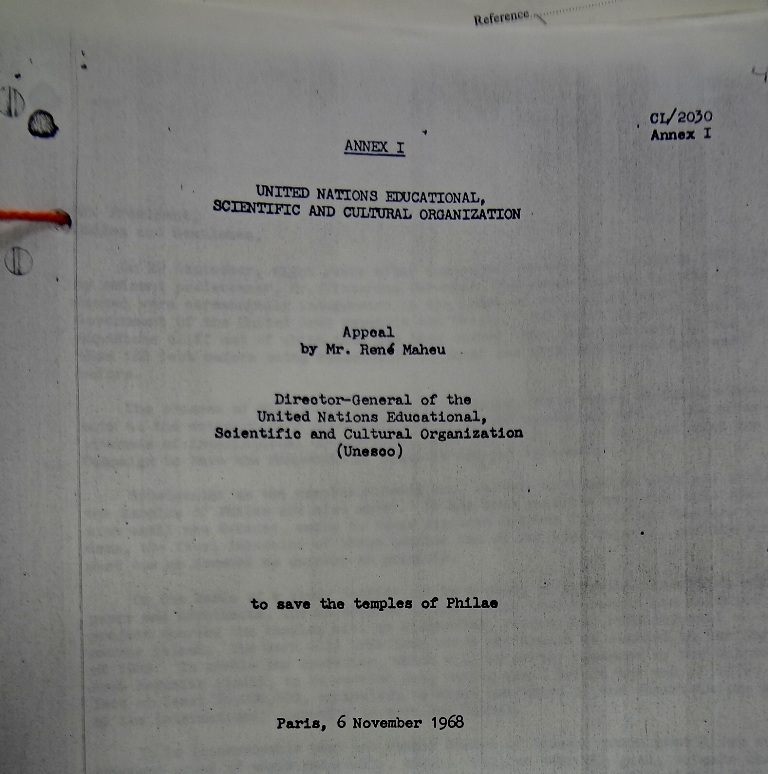

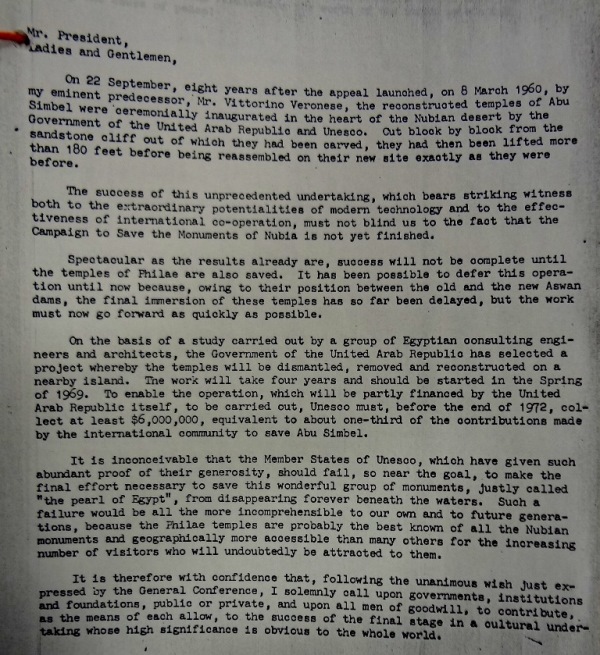

On 6 November 1968, following the overwhelmingly successful campaign to save the temples of Abu Simbel, UNESCO launched an appeal to save the temples of Philae. The Director General, René Maheu, celebrated the inauguration of the newly reconstructed temples of Abu Simbel, and added: ‘spectacular as the results already are, success will not be complete until the temples of Philae are also saved’ (FCO 13/364). It was estimated that saving Philae would cost $12,270,500 and take five years (OD 24/114).

- René Maheu’s appeal, 6 November 1968 (catalogue reference: FCO 13/364)

- René Maheu’s appeal, 6 November 1968 (catalogue reference: FCO 13/364)

- René Maheu’s appeal, 6 November 1968 (catalogue reference: FCO 13/364)

The UK had taken part to the 1960-1968 Abu Simbel campaign and was now wondering whether more funds should be pledged – and, more importantly, whose budget these funds should come from. Peter Hayman, the Deputy Under-Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, thought that ‘one way or another, the British cultural experience, now and in the future, [would] suffer loss if Philae [was] not saved or if we [did] not help to save it’ (FCO 13/364). Besides, Anglo-Egyptian relations were ‘at their happiest’, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office was keen to ‘develop that side of things as an insurance against more difficult relations on e.g. the Arab/Israel dispute’. Admittedly, it was difficult to find criteria for judging what might be a reasonable sum to offer, especially as British funds sequestered in 1952 were still blocked in Egypt. Plus the UK had already contributed £75,967 to the last appeal (WORK 14/3074).

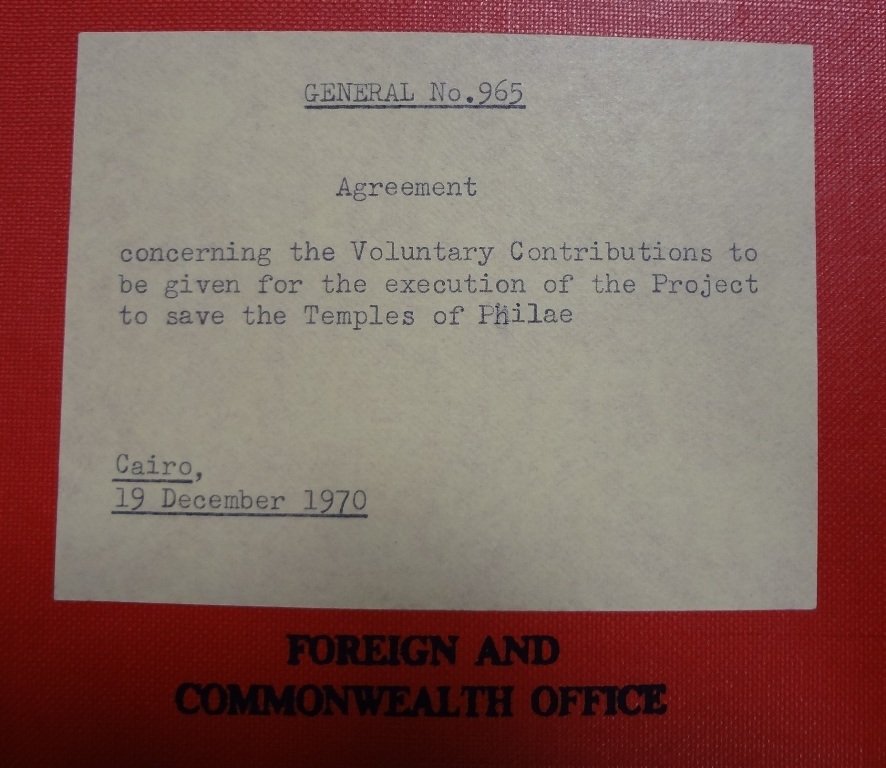

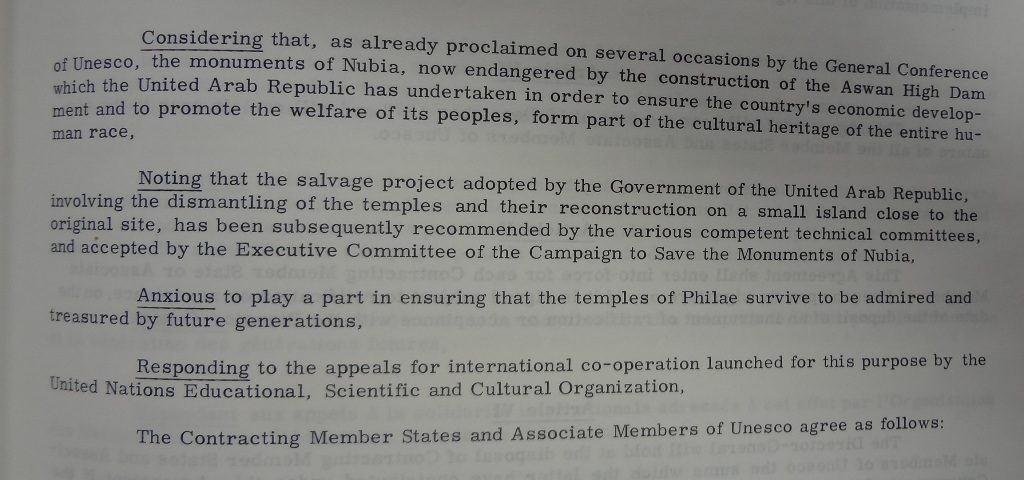

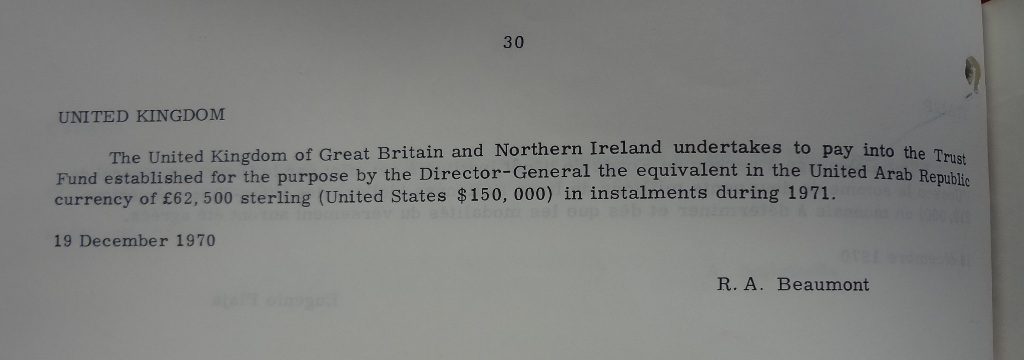

In the end, Britain was ‘anxious to play a part in ensuring that the temples of Philae survive to be admired and treasured by future generations’, and signed the Agreement concerning the Voluntary Contributions to be given for the execution of the project to save the Temples of Philae on 19 December 1970 (FO 949/102). The country pledged £62,500 ($150,000), to be paid in instalments during 1971.

- Agreement concerning the Voluntary Contributions to be given for the execution of the project to save the Temples of Philae, 19 December 1970 (catalogue reference: FO 949/102)

- Agreement concerning the Voluntary Contributions to be given for the execution of the project to save the Temples of Philae, 19 December 1970 (catalogue reference: FO 949/102)

- Agreement concerning the Voluntary Contributions to be given for the execution of the project to save the Temples of Philae, 19 December 1970 (catalogue reference: FO 949/102)

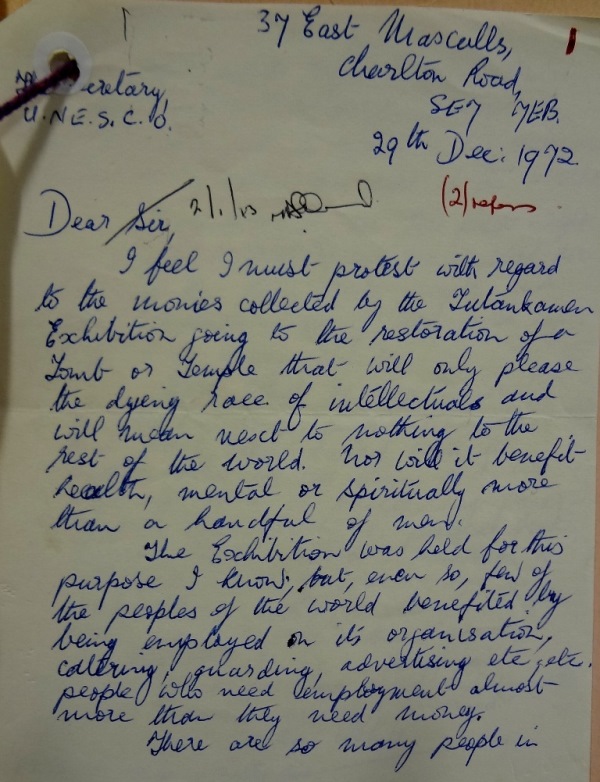

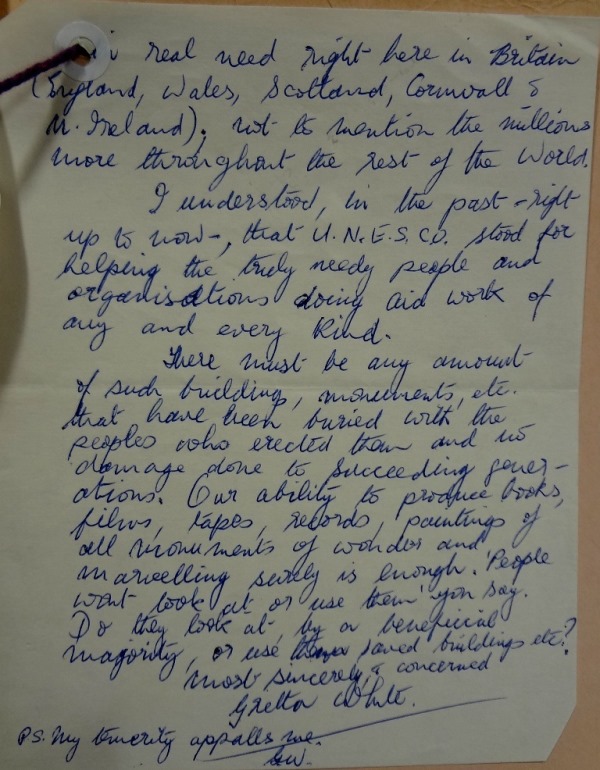

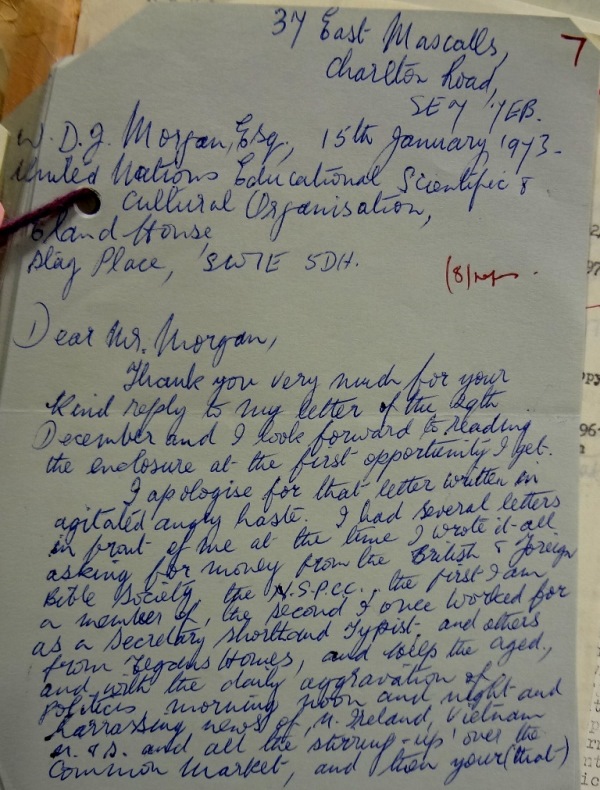

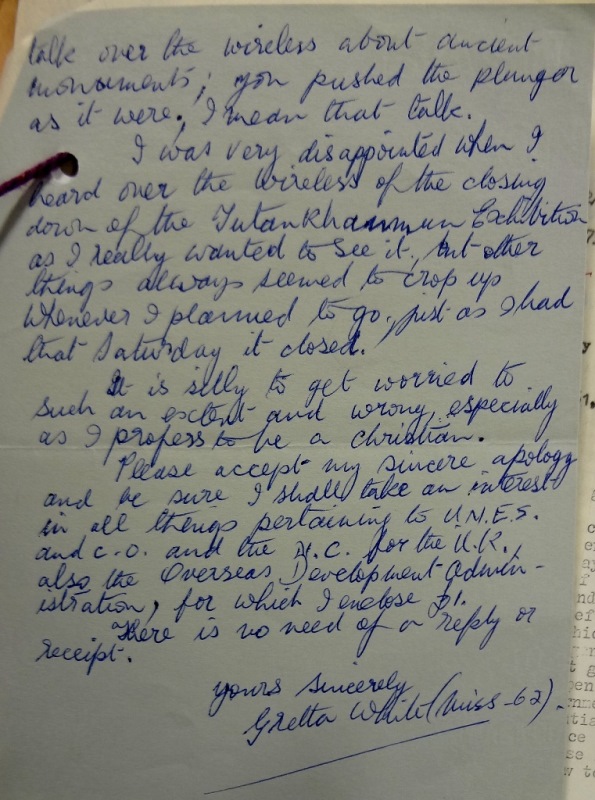

The UK also decided that all the proceeds of the 1972 Tutankhamun exhibition at the British Museum would go towards the rescue of Philae. This seemed a rather good idea, but not everyone was delighted at the prospect. A Miss Gretta White wrote in on 29 December 1972, complaining bitterly it would ‘only please the dying race of intellectuals and mean next to nothing to the rest of the world.’ She received a very polite answer and a booklet on UNESCO, and actually repented on 15 January 1973, apologising for her first letter ‘written in agitated angry haste’ because she was so disappointed at not having managed to get tickets for the exhibition. She also generously enclosed £1 ‘for the Overseas Development Administration’. Procurement being Procurement, the pound was promptly returned.

On 2 May 1973, a £600,000 cheque was handed to UNESCO’s Director General for the Campaign; a further sum (£57,731) was added when the accounts were completed (OD 24/149).

- Gretta White’s letter, 29 December 1972 (catalogue reference: OD 24/149)

- Gretta White’s letter, 29 December 1972 (catalogue reference: OD 24/149)

- Gretta White’s letter, 15 January 1973 (catalogue reference: OD 24/149)

- Gretta White’s letter, 15 January 1973 (catalogue reference: OD 24/149)

It was decided to move the temples of Philae onto the island of Agilkia, some 300m downstream, as the monuments could then be kept in their original disposition. In 1972, the construction of a coffer dam (not unlike that of Mr Watt’s) started around Philae, and took two years to complete. The water was pumped out and all the mud and algae had to be removed from the monuments before a photogrammetric survey could be made (to record the inscriptions and ensure the monuments could be reassembled properly). The temples were then dismantled and the blocks carefully numbered while Agilkia was landscaped in the shape of a dove, like the original island.

In 1976, the British Royal Navy partnered up with the Egyptian Navy to recover the Gate of Diocletian, which had been outside of the coffer dam, followed in 1977-78 by the temple of Augustus (DEFE 24/1421). These monuments had been the last to lie under Lake Nasser. Philae had been saved and reopened to the public in 1980. The ‘dying race of intellectuals’ was very pleased indeed, and so was everyone else.

To this day, Philae remains, in the words of René Maheu, the place ‘where the genius of ancient Egypt, in contact with Greek art, has brought forth one of these marvels of grace, which make poets dream and which prove to what refinement an intermingling of cultures can lead’ (OD 24/114).