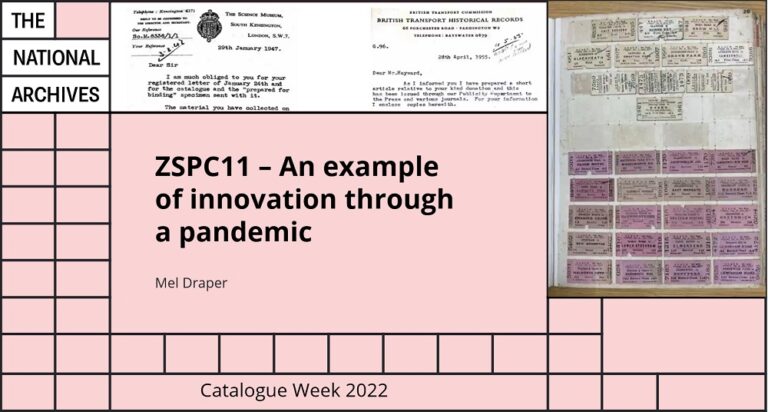

For Catalogue Week 2022, lead volunteer Mel Draper traces the work of the ZSCP 11 volunteer team’s work as they develop sophisticated technical solutions to negotiate new ways of working during the recent pandemic.

Transcript

Hello, my name is Mel Draper, a member of a small team working on a Special Collection at The National Archives, ZSPC11. I’m going to give you a short talk on the innovative steps we took which allowed us to continue working on this collection through the recent pandemic.

I’ll start by giving you some background on the collection and why it is at The National Archives, before moving on to show how we’ve changed the way in which we’re building its catalogue data.

The collection didn’t belong to some special dignitary, or well-known person, but is a personal collection of railway-related material from a wide variety of sources, including a few items from influential people in the railway industry.

The collection is now split between the National Railway Museum at York, and The National Archives at Kew, roughly on the principle that three-dimensional artefacts are at York and paper-based material at Kew. As you can see it is by no means a small collection.

Mr Hayward, the man who assembled it, was a rather ordinary individual. For most of his life he lived in Weston-super-Mare, near Bristol. He was married, although there is no record of what his wife thought about having all this collection in their home! As far as we know, they had no children, so there was no call for the collection to remain with his family when he died.

He certainly promoted the collection during his lifetime, and even in the early post-war period, tried to get the establishment interested in its preservation. This was initially through contact with the Science Museum; the director even made a personal visit to inspect it during the 1947 Big Freeze – but that’s a story for another time! Once the railways were nationalised, the government established the British Transport Historical Records Office, which agreed to receive it under a gift agreement.

On the winding up of that office in the mid 1990s, the collection transferred to the NRM and TNA.

As far as the material at Kew is concerned, it can provide a researcher with an excellent starting point for their investigation of a particular aspect of railway history in Britain, and to some extent, overseas. The material was carefully collected and systematically stored in large ring-binders. There was a simple catalogue of the binders, but no record of the individual items within the binders.

Such an item-based catalogue would make access to the collection much more useful to researchers. A project was started at TNA to do this, but it quickly became clear that more help would be needed. TNA approached the NRM, which provided some volunteers, via their Friends’ organisation, to form our team. We worked steadily through the last decade and made good progress in cataloguing the contents of the 420 binders.

We did the work on site at TNA, entering the item details directly into the PROCAT computer data- base system. Team members use their own, or collective specialist knowledge of railways, to make the descriptions accurate and useful to researchers; that often requires more investigation of the items using external specialist reference material. All was going well, and by the end of 2019 we were over 80% of the way to completion – but we all know what happened then.

It was obvious the world was facing a serious challenge which was going to disrupt regular working. At TNA, there are two binders we had been reluctant to start – the two holding the large collection of railway tickets. Not only are individual tickets time consuming to identify and catalogue, but many of the tickets are valuable in their own right and are therefore accessible only under invigilation in the secure reading room at Kew. We had thought for some time that the best way to tackle these binders would be to photograph each sheet of the binder and capture the details of the tickets at leisure, rather than spend weeks in the secure room. The looming pandemic provided the catalyst to kick this off, so we quickly got agreement to photograph the two binders – and just in the nick of time. Once the national lockdown was declared on 23 March, we were ready to start working from home using the photographs which had been stored on a DVD. The description of each ticket was captured into a text file on our home computers, each person working on a page of the ticket album. These text files were then uploaded into a shared storage area on the internet.

Everything was going well for a couple of months and then we realised there were a few problems we needed to sort out. As I mentioned, when we were working on site at Kew, we often worked together to clarify the description of more difficult items. We also realised, perhaps obvious really, that we will ultimately need to get the catalogue data from the text files into PROCAT – once we could get into TNA again. Finally, the more we worked, the more it was clear that the complexity of the information leaves lots of possibilities for formatting and other errors. To illustrate the point, take a look at this example of a catalogue entry for one sheet of tickets.

Tickets are a good example of small things that often need long descriptions. However, even a comma or bracket in the wrong place can change the meaning. Even with shortened descriptions, it’s difficult to keep within the 8,000 character limit allowed for an item entry in TNA’s PROCAT system. Just looking at such a dense mass of details can give you a headache, so spotting mistakes is very difficult.

The solutions we came up with for our three problems were:

First, to hold regular video conference meetings. These allowed us to share the images of problem tickets, hold a discussion, and agree the descriptions.

We also looked at the alternatives for getting the data into PROCAT. Re-typing everything back into the TNA computer wasn’t an attractive idea. First, there was likely to be limited access to TNA for many months. Second it doubles the amount of typing for each item, and third, in re-typing the data it increases the chances to introduce more errors. The alternative, suggested by TNA staff, was to convert the text files into a spreadsheet which can be automatically uploaded into PROCAT, so avoiding the need for re-typing. But how to make sure the data in the text file is correct? That’s a tough one. Clearly we needed something we can run on our home computers which can make the required checks and prepare the spreadsheet at the same time.

By the second half of 2020, we’d shown that it is feasible to do cataloguing work from photographs of the tickets. There were some limited opportunities to get into TNA, so I went in to take photographs of some of the other binders. In addition, when lock-down happened, we, like everyone else, had to leave the catalogues we were working on. It would be a shame to lose all that work, so we decided to photograph those binders and look for a way to get the data out of PROCAT into our computers. That proved to be a bit more complex than it sounds, as PROCAT doesn’t have a way for data abstraction. The solution was to photograph the PROCAT screen and then use optical character recognition to reconstruct the entries as digital text. It worked remarkably well, with only a few tweaks needed to the recognised data. In the meantime, I was working on the computer program to do the spreadsheet creation and data checking.

It took a while, but the program was operational by the end of 2020; it’s gone through further development since then. It runs on a home computer and just needs the user to point it at the text file. This slide shows a sample of the display. You’ll see that it detects all the dates mentioned in the item description and compares these against what the user believes is the date range. In most cases it will throw up a warning, so that the user can double check.

If you think that is trivial, think back to the list of tickets I showed earlier; there could well be 30 or more tickets, possibly each having a date. The program also makes around two dozen individual format checks of the entry against the TNA guidance, looking for things such as mismatched brackets; correctly formatted names, abbreviations, measurements, and currency; lack of full stops; duplicated commas; correct use of quotations and so on. At the end, it cross-checks the date range of the entire piece, often of some 80 or more items, and works out the recommended piece level date range.

As well as producing the spreadsheet, it also produces a series of interlinked web-page displays which show mock-ups of each item as it would appear in a TNA Discovery search. Anything which the user ought to check is highlighted, with some hints drawn from TNA guidance – in this case the formatting of a person’s name. The computer produces a record file for all the potential problems it finds, effectively a hard copy of what is shown on the screen in the previous slide. The user can comment out any of these which are known to be correct. That will prevent the problems being flagged up again when the program is re-run on the text file. The ultimate aim for the user is to run the program run and get an “ALL CLEAR” message.

Testing the program and the new method of working, took place during last year. One interesting test was to use TNA’s Discovery to download an existing catalogue for one of over 300 binders already in the TNA database; actually one I own up to preparing in 2018. The resulting spreadsheet was converted back into a simple text file and run through the program. I was surprised how many formatting corrections it showed were needed. This was despite the original catalogue data having been manual checked by me and others when it was prepared using PROCAT. It certainly proved the effectiveness of the computer-based checking program.

Next was to check that the computer-generated spreadsheet could be uploaded into Discovery without problem. To test this, we used a spreadsheet which included the optical-character recognised PROCAT data from a part completed binder, subsequently completed using data from the photographs of the binder. Once the computer program declared it as “ALL CLEAR” of formatting and date errors, the spreadsheet was uploaded into Discovery. We repeated the earlier test, by searching Discovery for that binder’s catalogue, downloading the entries as a spreadsheet, then running it through the program. Comparing the results with the earlier computer run, showed that no errors had been introduced during the uploading process.

This slide shows what part of the spreadsheet looks like – there are another 80 lines like this in this particular spreadsheet file. You’ll realise that it is virtually impossible to check the formatting of such a spreadsheet manually. So comparing the data before and after the uploading into Discovery, gave us confidence that we can trust the new remote preparation and uploading process.

Well where are we now? We have photographs of nearly half of the remaining binders. 14 of these have catalogues prepared as text files and are at various stages of final checking. Some binders still need the items marking with their reference numbers before we can upload the catalogues. Five pieces have been uploaded into TNA’s Discovery database using the new system, and the catalogue data and binders are now available to the public.

While we still need to make visits to TNA to photograph the remaining binders and mark up the items in them, we have shown that the rest of the work can be done from home. The computer-based system has been proved to enhance the accuracy of the data formatting and date ranges. By working from home it has allowed team members to be more productive by avoiding the need for travel. It enables flexible working times, and means we have ready access to our own extensive libraries of reference material. The end result is that the team is still together, despite the two years of lock-down restrictions; and there is a growing catalogue for this unusual collection which is easier for researchers to use in finding items of interest.

All we need to do now is finish the remaining binders.

Thank you for listening, and I hope you found the talk interesting.

Jane Langford writes: I am delighted to announce that Mel was awarded the Bringing Innovation Award at the London Heritage Volunteers Award Ceremony 2022.