On 15 September 1973 Mr Lorne Horsford went out to the Mecca Palais dance hall in Leicester with his girlfriend. Mr Horsford was refused entry despite being sober and adhering to the required dress code. His girlfriend, Sue Kepka, was allowed to go in.

Mr Horsford concluded that he was being refused entry because he was black, and decided to lodge a complaint under the 1968 Race Relations Act (under which it was illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to someone because of their race or ethnic background).

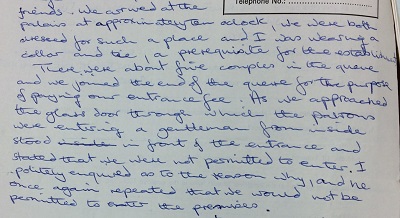

Section of Mr Horsford’s complaint to the West Midlands Conciliation Committee (catalogue reference: CK 2/367)

This complaint, along with many others, can be found in files from the Race Relations Board held at The National Archives in record series CK 2. In his complaint, in file CK 2/367, Mr Horsford explained that:

‘As we approached the glass door through which the patrons were entering a gentleman from inside stood in front of the entrance and stated that we were not permitted to enter. I politely enquired as to the reason why, and he once again repeated that we would not be permitted to enter the premises. I then remained outside and paid for Miss Kepka (who is my girlfriend and she is white) to go inside so that she could contact our friends who were all already inside… All the members of the staff refused to comment as to the reason why I was refused admission.’

A friend of Mr Horsford, D B Wilson said in his statement:

‘I was inside the Palais when Sue came up to me in a very distressed state saying that they would not let Lorne in. I went straight up to the man on the door and asked why they had refused Lorne admission and the reply was “no comment”… I spoke to a Policeman in the foyer. I pointed out to him that the notice on the wall* was subject to the Race Relations Act. He was not interested… While I was in there (3/4 hour) I only saw one coloured girl inside. She had told Sue that she was only allowed in with some difficulty.’

The standard procedure following a complaint under the Act was, in the first instance, for a local Conciliation Committee to consider the complaint and to try and resolve it. If this failed then it would be referred to the Race Relations Board and potentially taken to court. Mr Horsford’s case was dealt with by the West Midlands Conciliation Committee which held a meeting with Mr Preedy, the Mecca Regional Director, and Mr Lakin, the General Manager at the Palais.

Miss Atkin, the conciliation officer, wrote in her report of the meeting:

‘[Mr Preedy] said that assuming Mr Horsford was properly dressed and had not been drinking, then the only reason he could give for Mr Horsford being refused entry was connected with an incident which had taken place a fortnight earlier in the top floor Disco. Mr Lakin said that on this occasion a number of coloured youths had bonded together as had a number of white boys. A fight broke out which Mr Lakin thought had originated in two people arguing over a girl… After the fracas Mr Lakin asked the staff involved if they would in future turn away anyone who looks even remotely as though he was connected with the incident.’

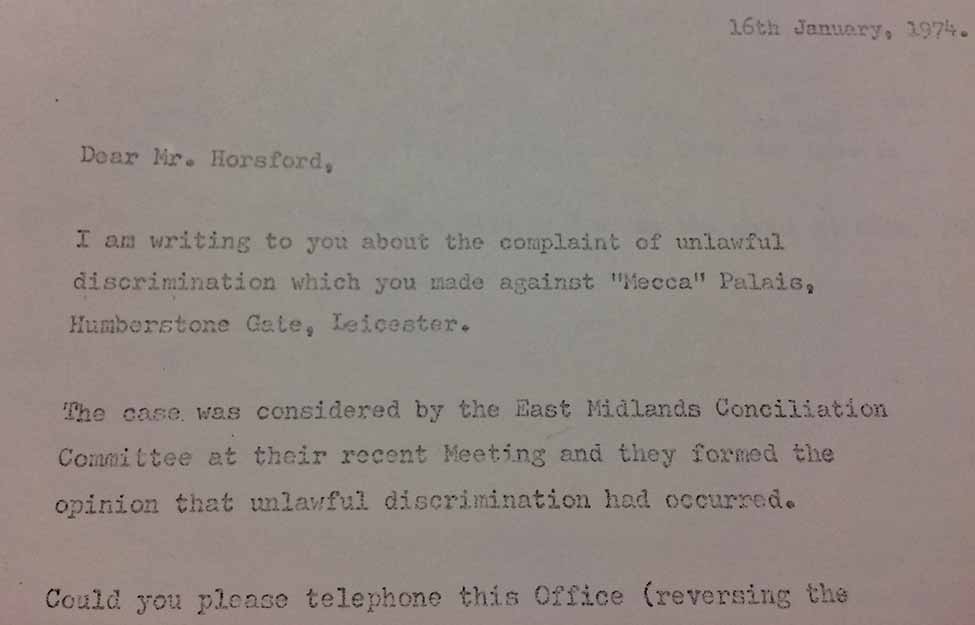

Following the meeting with the Mecca Palais managers, the West Midlands Conciliation Committee wrote to the company to say that a breach of the Race Relations Act appeared to have taken place.

Letter from West Midlands Conciliation Committee (catalogue reference: CK 2/367)

The Chairman and Managing Director of Mecca Limited, Eric Morley, responded, saying:

‘This company does not, and will not, practise unlawful discrimination … We will, however, continue to exercise our right to refuse admission to people for any reason whatsoever, except that of colour, race or creed. It is our duty to protect our patrons and our staff, and that we shall continue to do. …To accept the Race Relations’ contention that we can refuse admission to white people but not coloured is placing us in a position which we are not prepared to accept.’

The Conciliation Committee continued to attempt to negotiate a settlement between Mr Horsford and Mecca Limited. In one exchange Mr Horsford wrote:

‘I have decided that the sum of £5 would not be sufficient to cover any inconvenience and embarrassment. Therefore I have decided to ask for a more ridiculous sum of £20. At this sum Mecca would be less likely to settle and they would be forced to do what I want them to do and fight the case. The publicity I could give this case is worth far more than £5.’

Mecca refused to settle, but instead offered to invite Mr Horsford ‘to a public dance night at the Palais Leicester, as our guest together with his lady and to note that coloured people are using the facilities as well as white people and that there is no racial discrimination.’ Mr Horsford responded to the offer saying ‘I have not the slightest intention of going back to the Palais and therefore I wish to stick by my original terms of settlement.’

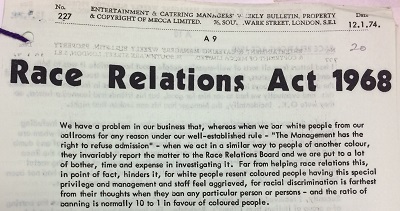

Interestingly, there were already a number of other cases being brought against Mecca by the Race Relations Board. The common theme of the company’s response was that in order to protect their staff and patrons, they needed to have the ability to control who came in to their dance halls. Mr Eric Morley sent the Conciliation Committee a copy of the company’s weekly bulletin in which he wrote:

‘…those who go to their comfortable beds each night should, perhaps, try a month in a ballroom where the manager and his staff are liable to be the victims of physical encounters any day of the week. Without the weapon of refusing admission, he would have no chance, and I will fight tooth and nail to protect that right for him.’

Mr Morley also argued that his managers refused admission to many people on many different grounds, and that refusing Mr Horsford was not an indication of discrimination. He cites examples of barring boys from ‘a school for the Deaf and Dumb’ because fights had broken out when ‘one of their boys, a powerful figure, was often misunderstood by his gestures…[and] he would be involved in a fight and all the boys from his school would join in.’

Section of Mecca Limited’s newsletter, January 1974 (catalogue reference: CK 2/367)

Mr Morley went on to say:

‘I could give you many examples of how and why we have had to ban people, including dress, hair, type of footwear and so on, and this has included ladies, some of whom are troublemakers because they provoke fights, but keeping to the case of the deaf and dumb boys for the moment and imagining they were coloured – off they would go to the Race Relations Board and our well-meaning friends would find us guilty of exercising racial discrimination.’

Unable to reach a settlement with Mecca, the East Midlands Conciliation Committee referred the case on to the Race Relations Board. The Board decided to take the case to court and it was heard in Nottingham County Court in June 1975 with a judgement given in November the same year.

The judge found that Mecca had indeed contravened the Race Relations Act and awarded damages of £40 to Mr Horsford. However, he also made a point of expressing his understanding that Mecca faced a difficult task in keeping order in their dance halls, saying:

‘There is no doubt that the main weapon in the hands of Mecca Limited is to refuse admission to would-be trouble makers. It is how they exercise this refusal that is called in question in the present case … I hope sincerely that the present proceedings will … establish a dialogue between the Board and Mecca which will help Mecca Limited on a practical level to solve a very difficult problem.’

There were numerous other cases brought to the Race Relations Board around this time. File CK 2/148 contains an interesting summary of those cases the Board considered taking to court in the seven years between the 1968 and 1975 Race Relations Acts.

Over this period, 366 cases were referred to the Board, and in 122 of these cases, involving 101 respondents, the Board decided to proceed towards a court hearing. 31 cases were still proceeding as the report was written, but of those that had concluded 22 were settled out of court; 15 were withdrawn or terminated by the Board; 33 went to court. Of these, 23 were found in favour of the Race Relations Board.

To find out about researching race relations in Britain read our guide on black British social and political history in the 20th century.

*[presumably about the management reserving the right to refuse admission]

Mr Morley coming up with excuse after excuse. Just didn’t get it. Love to know where he is now.

Thanks for your interest in the blog. The content of the Mecca newsletters is fascinating and shows how attitudes have changed.

Great!