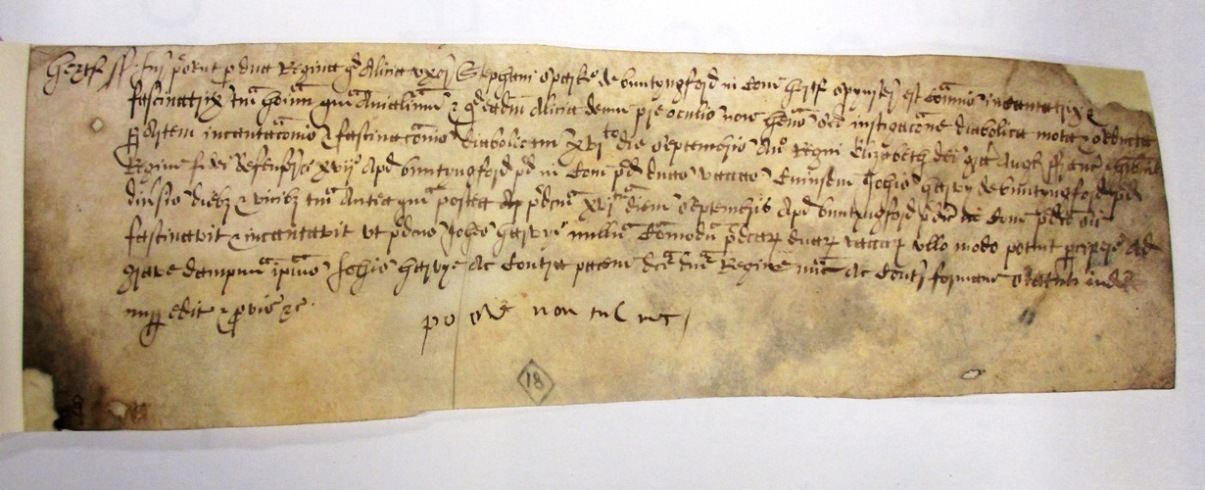

The indictment of Alice Sparke, who was put on trial for witchcraft on 23 March 1576. Document reference: ASSI 35/18/5 m 18.

You live in a village in 16th century England and you keep two cows. Sadly, your cows are not thriving and you are concerned for their welfare. Do you:

a) Change their diet?

b) Treat them with leeches?

c) Kill them, sell the meat and use the profit to buy better cows?

d) Accuse someone of bewitching them?

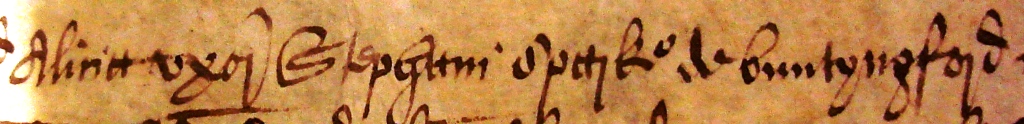

John Harvy, from Buntingford in Hertfordshire, chose option d. He accused a woman named Alice Sparke of being an ‘enchantress and witch’. Alice denied the accusation and was put on trial for witchcraft at the assizes in Hertford on 23 March 1576.

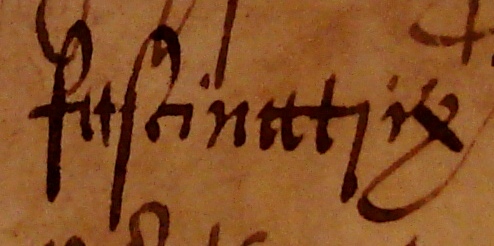

To 21st century eyes, the ‘long s’ in ‘fascinatrix’ (‘witch’) looks like a letter f without a crossbar. Document reference: ASSI 35/18/5 m 18 (detail).

Assize courts were one of many different types of law court in England in the 16th century. Criminal trials at the assizes dealt mostly with offences that were considered to be more serious. These varied from murder to vagrancy, and included forgery, the theft of relatively expensive goods, and witchcraft.

Few details of Alice’s case survive. The only record that we have is the piece of parchment shown above. [ref] 1. ASSI 35/18/5 m 18. [/ref] This is the indictment, a formal statement of the charges against the defendant. After the trial, a note would be added at the bottom of the indictment to record the outcome. In this case, the note reveals that Alice pleaded not guilty or, in the phrasing of the time, ‘put herself on the country’. The jury found her not guilty and she was set free.

Criminal trials relating in some way to cows seem to have been fairly common around this time and several others took place at the Hertfordshire assizes in the mid 1570s. For instance, on 27 July 1576, Robert Pytkyn, a shovel maker, was found not guilty of sexually abusing a red cow belonging to Henry Golde. [ref] 2. ASSI 35/18/7 m 11. [/ref].

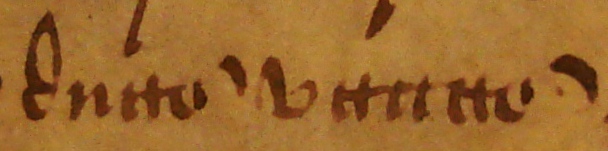

The Latin words ‘duas vaccas’ (‘two cows’). Document reference: ASSI 35/18/5 m 18 (detail).

On 11 July 1575, John Payne, a famer, was found guilty of stealing six cows, worth a total of £10 (roughly the equivalent of £1,500 today). [ref] 3. ASSI 35/17/6 m 4. [/ref]. The standard sentence for being convicted of stealing such valuable goods would have been death by hanging but John Payne was given ‘benefit of clergy’. This does not mean that he was a priest. At this period, a man who could read (or who could pretend to read by memorising the required passage from the Bible) could be given a lesser sentence for certain crimes, if it was his first offence. Being ‘allowed clergy’, meant that John Payne would have been branded on his thumb and given a short prison sentence. If he was lucky, he might even have escaped the branding.

Witchcraft was also often punished by hanging and, as a woman, Alice Sparke would not have been allowed benefit of clergy, so she was doubly fortunate to be acquitted. However, some women managed to avoid being hanged by claiming (either truthfully or falsely) to be pregnant. Expectant mothers were not supposed to be executed, so hanging would be deferred until after the baby was born and often this turned into a permanent reprieve.

When so little information survives, the records can raise as many questions as they provide answers. For instance, I wonder what John Harvy’s cows were doing (or not doing) that made him think they had been bewitched. Did they stop giving milk? Did they kick him? Perhaps they just fell ill. Why did he accuse Alice Sparke and not somebody else? She may have been a harmless old woman who kept a black cat, but she may equally well have poisoned the cows with yew berries and got away with it. We simply don’t know.

For me, this sense of incompleteness is partly what makes these records so fascinating. 16th-century assize indictments provide a partial, tantalising snapshot of past events and of people who lived and died long ago.

'Alicia uxor Stephani sparke de buntyngford’. The Latin text translates as ‘Alice wife of Stephen Sparke of Buntingford’. Document reference: ASSI 35/18/5 m 18 (detail).

Researching criminal trials

Finding information about criminal trials can be fairly difficult and complicated, especially if, like me, you are not an expert in legal records. Here are some of the reasons why it can be difficult.

1. Trials were held in various different courts and it is not always obvious which court would have heard a particular case. The National Archives holds records for some courts but records for other courts are held in different archives. Our brief online guide and overview of law courts may help you get started.

2. The amount of information available about a particular trial varies considerably: there may be very little or there may be a great deal. In particular, many older trial records do not survive. For 20th century cases, detailed records relating to more serious crimes (such as murder) are more likely to have been kept permanently than for less serious offences. Full transcripts of trial proceedings are rare.

3. Many trial records are not catalogued in detail and it is not usually possible to find everything just by searching online. (There are exceptions, such as the Old Bailey Online website). You will normally need to have some idea of when or where the trial is likely to have taken place. It is worth bearing in mind that you may need to look at several different records to find all of the information relevant to one case.

4. The records can be hard to read and understand. [ref] 4. Even experienced researchers or professional archivists sometimes find old records quite difficult to read. For Alice Sparke’s case, I used the description of the indictment in J S Cockburn (ed), Calendar of Assize Records: Hertfordshire Indictments Elizabeth I (HMSO, 1973), entry 59 to help me. [/ref]

- Many older records (including assize indictments up to 1733) are written in Latin, with many of the words abbreviated. If you want to learn some Latin, there is a beginners’ tutorial on our website.

- Whether the records are written in English or in Latin, they often use unfamiliar or confusing terminology. For instance, John Payne was convicted of ‘grand larceny’, meaning the theft of goods worth at least one shilling. Robert Pytkyn was tried for ‘buggery’. In 16th century trial records, buggery is much more likely to refer to a man sexually assaulting an animal than to intercourse between two men.

- Some legal records include repetitive and long-winded phrasing, with frequent use of words like ‘whereas’ and ‘aforesaid’.

- The style of handwriting in older records may be very different from printed text or modern handwriting, and it may be quite untidy. You may find our online palaeography tutorial helpful.

If you need to do in-depth research, it is sometimes best to start by reading a book. Criminal Ancestors, by David Hawkings, [ref] 5. David T Hawkings, Criminal Ancestors (Stroud, 2009). [/ref] is a useful book for family historians and others looking for individual people. If you are interested in late-16th or early-17th century assizes as a subject, the introductory volume to J S Cockburn’s Calendar of Assize Records [ref] 6. J S Cockburn, Calendar of Assize Records: Home Circuit indictments Elizabeth I and James I: Introduction (HMSO, 1985). [/ref] explains how the assize courts worked during the late 16th and early 17th centuries and outlines the content of the surviving records and the difficulties involved in interpreting them.

Two cows (not bewitched). Document reference: INF 9/1023/3 (detail).