This blog series has explored many of the medical advancements the First World War enabled; warfare made medical advances a priority.

However many aspects of medical technology were already in development before the war. This post will explore x-ray apparatus that had previously existed, but where the conflict hastened significant developments that meant technology could be adapted to the often harsh and varied terrain of the battlefield.

‘Photograph of a Crookes X Ray Tube showing Rontgen Rays’ from 1905 (catalogue reference: COPY 1/491/410)

Radiation was originally discovered by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen in the late 19th century. One of the early ways x-rays were used is through an x-ray tube. The image opposite shows an early photograph from 1905 of a Crookes x-ray tube showing Rontgen rays (so named after their inventor, and now commonly known as x-rays).

X-rays and their uses

X-rays in the context of the First World War were principally used to identify foreign metal lodged in the body. Reading the samples of medical registers it is not surprising this apparatus was highly used, with gun shot wounds often mentioned as a cause of injury. Browsing through pension records it also possible to note the wide variety of other conditions x-rays were used for, from neuralgia to deafness. Records in our collections of the Munitions Invention Department document two principle reasons these advances in technology were so important; first, to save lives directly as a result of injuries and second, to prevent illness from the spread of infection from foreign objects. Infection continued to be one of the biggest killers through out the war.

Despite this urgent need for x-ray equipment towards the beginning of the conflict the skills and research in this area were in short supply, specifically the glass apparatus. With the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research commenting that ‘The x-ray tube industry in this country is in the hands of only a few small firms, with limited funds and working largely without proper scientific assistance.’ (DSIR 36/3367).

Mobile x-rays

While this technology existed, how, practically, could you get this help as close to the front line as possible? As my colleague David explained in a previous post, there were many stages a casualty could go through – the closer the x-ray machine was, the more chance of saving a life.

Portable x-ray equipment was developed in response and military x-ray units were charged with providing this service.

War Diaries survive for these X-Ray Units, such as the Number 2 Cheltenham College Mobile X-ray Unit which briefly details procedures done by the unit, and the Number 4 Mobile X-Ray Unit, which lists the amount of individuals needing x-rays each day of the conflict under the unit. X-ray machines were also fitted on hospital ships, such as the Formosa, challenging the technological advances of the time.

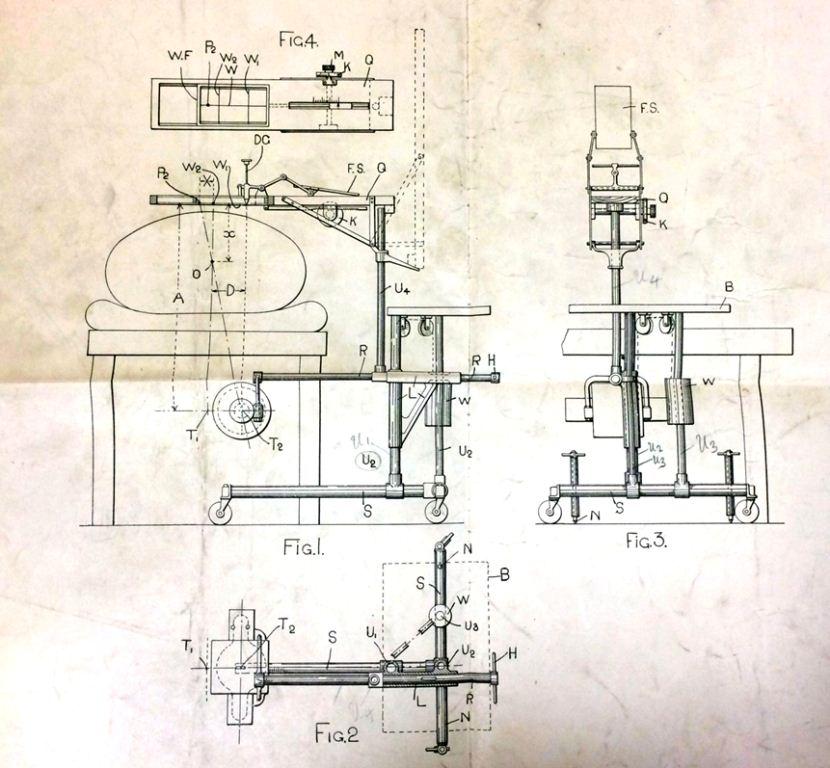

Portable x-ray equipment was fitted into ambulances to help the speed with which this help could be given. A diagram of the ambulance equipment survives in our collections. The equipment shown in the drawing is the smallest which can conveniently accommodate all the apparatus required while providing enough space to help the patient. The objects were expensive and difficult to raise funds for – The Common Cause, the organ of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, reported that the London Society for Women’s Suffrage had sent an x-ray ambulance at the cost of over £1000.

Aftermath of War

These medical advances however came at a cost. The consequences of working with munitions, both explosions and TNT positioning, have been discussed in historiography of the war, causing numerous problems to individuals in later life. However the effect of x-rays exposure was largely unknown; as Marie Currie died of radiation exposure, so did others.

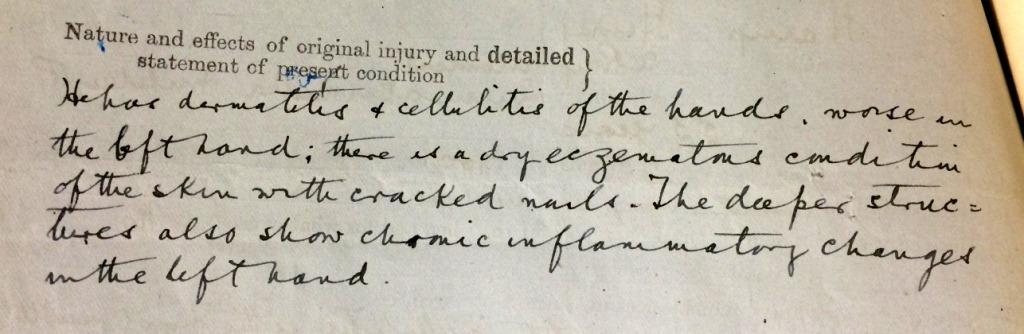

Extract from a compensation claim by H Henry an x-ray operator at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital, Millbank (catalogue reference: T 1/12518/13598)

Compensation was given to workers after the war who suffered the effects of working with radiation constantly, such as in the case of Harry Henry. Harry worked as a radiographer at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital from 1900, with an increased work load through the war, and by 1919, he was suffering from dermatitis and cellulitis as a consequence. As the Workmen’s Compensation Act 1906 was not found to be applicable, Henry was instead awarded money from a Compassionate Fund.

The war therefore hastened technological advances but clearly there were consequences to such fast developments in medical procedures, both positive and negative.

Look out for the next post by my colleague on medical technology in a month’s time.

We are looking to trace early evidence of radiation protection manufacturers.

I work for a company called Rothband and we have historic record showing our first lead apron to be manufactured taking in place in 1911, which is in line with when diagnostic medical imaging came into the UK, we even have a test radiograph.

I am looking to trace any earlier contenders for the inventor of the lead apron, so I am casting my net out to see who is there.

Hi, Im trying to source archival X-rays, MRI or CT scans to use in a photographic project any ideas where I can get these from?

Sorry, bit late but yes. Contact the website owner.

I’ve just read Ivan Bawtree’s war diary where he simply mentions “x rays”, whilst developing phots for the GRU near Ypres. Does this mean they had machines near the front line?