Sparkling wines produced in the United Kingdom today win international awards, and we import and consume wines from across the globe, from as far afield as Algeria, Japan, Jordan, Mexico, Moldova and Zimbabwe. But our enjoyment of wine is nothing new – we’ve been drinking it for centuries, and were exporting wines produced from British-grown vines across the Roman Empire.

Of course with demand comes opportunity, and as the examples of historical research below show, monarchs and Parliament since the 14th century have taken full advantage, leaving the rest of us to w(h)ine about taxes and duties[ref]The Quarterly Journal of Economics: The Origin of the National Customs – Revenue of England[/ref].

Exchequer and Chancery records

Early Exchequer records contain documents and references to the taxing of wines. The early tax was more a requirement to obtain a Royal license to import wines (and goods). The National Archives series E 122 contains various lists and ledgers on imported wines.

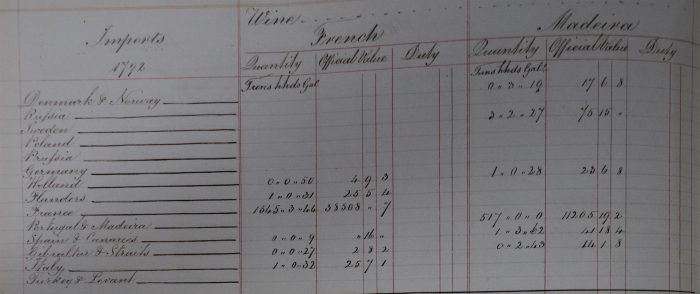

Customs ledgers of imports, 1792: TNA Ref: CUST 1/5A

Wines from Bordeaux were popular during the reigns of Edward II and Edward III – no surprise given England’s influence throughout France during the Hundred Years’ War. Duties on importing wines helped to pay the campaign costs. Diplomatic documents from 1310 show a list of shipments of wines at Bordeaux in TNA Ref: E 30/1520. The citizens of Bordeaux had complained about the duties levied on wines during the late thirteenth century (C 47/24/2/26).

Poet and author Geoffrey Chaucer wrote regularly about wine, so it’s hardly surprising that his son Thomas became the Chief Butler of England to King Henry IV.

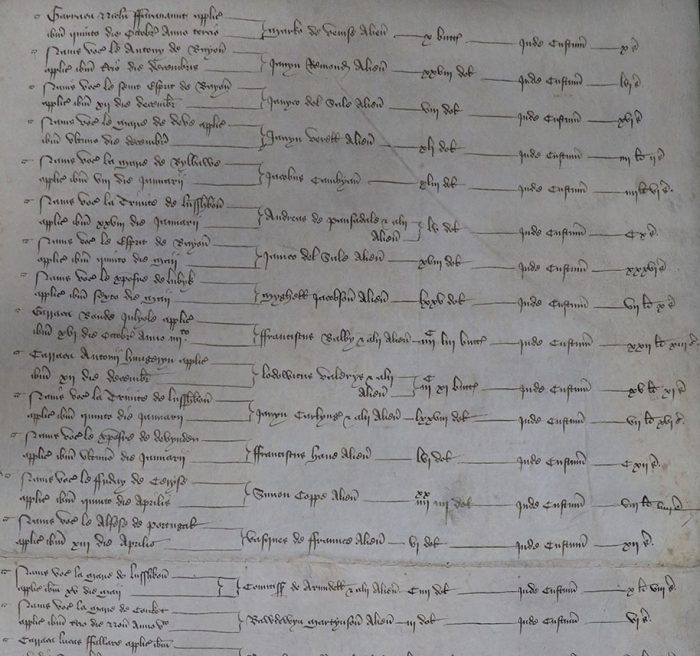

Account and particulars of the account of Thomas Chaucer, butler, duty on wines: TNA Ref: E 101/81/1

At the Battle of Agincourt, in 1415, the Duke of Orléans was taken prisoner by the English. The Duke was in line to be King of France, so he was not released until 1440. Part of the ransom included shipments of wine (TNA Ref: C 49/49/14).

In 1792, just prior to Napoleon and the Peninsular wars, England imported more than 1,545 tuns (equivalent to roughly 16,304,235 bottles) of wine with a value of £38,508 0s 7p (approximately £5.6 million today[ref]Estimate taken from 210 Gallons per Tun, and Bank of England inflation convertor[/ref]).

Diplomatic drinking

Wine merchants in this country didn’t just buy wine from France. Germany and Spain also exported to the United Kingdom. Madeira’s sweet wine was also very popular with the Courts of England. Although in 1576 Edward Castelyn wrote to Walsingham: ‘the vineyards are so blasted and marred through Germany that little wine will be made this year.’

Merchants in Exeter, Dartmouth and Southampton in 1639 can be found in the Order of Council (SP 16/421 folio 205), refusing to pay the 40s per tun wine duty.

Both foreign and British diplomats regularly requested the exemption of duty or tax on their wine. In 1654, during the Interregnum, the Ambassador Extraordinary of the United Province, France, was allowed to import French wine duty-free [TNA Ref: SP 25/75 folio 546).

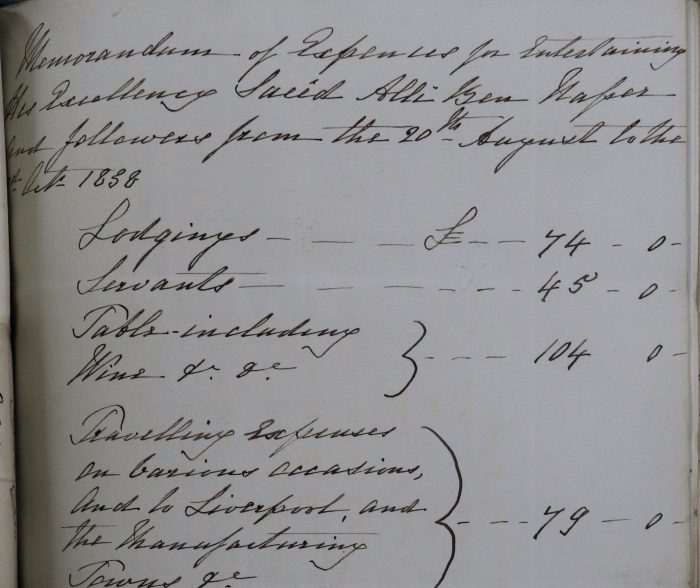

In 1838 the memorandum detailing the expenses in entertaining the Muscat Envoy, Said Ali Ben Nasir, showed a total amount of £418. The table including wine amounted to fully £104 of that total.

Chief Clerk’s records: Accounts for entertaining the Muscat Envoy, 1838. Catalogue reference: FO 366/284

A world of wine

The National Archives holds many more records relating to wine. London wine merchants Corney and Barrow have been established for more than 200 years. The Probat (TNA Ref: PROB 11/1817/138) and death duty (TNA Ref: IR 26/1316 entry 340) for Edward Bland Corney, who opened their original shop, is held here at Kew. There are also entries for Chancery cases in 1804 and 1806, where Edward Bland Corney is a plaintiff.

Australian and New World wine is nothing new either. The files in BT 31 of dissolved companies include traders such as the Australian Wine Company, Ltd, 1882, Imperial Australian Wine Company, 1900, and United Australian Wine Association Ltd, 1883.

Treaties and wine

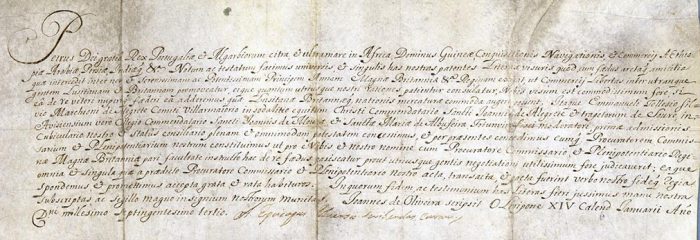

Present day controls on the duty we pay is set by the budget, and the duty payable on wines entering the country continues to be laid out in treaties. The oldest treaty in the Archives concerns wine: the Treaty with Portugal of 1703 stipulated the amount of tax payable on wine imported in to England.

SP108_389 Powers to the Portuguese ambassador to negotiate a Treaty of Commerce 8 Dec 1702

Further reading

The Wine Trade, by A D Francis, A & C Black, 1972.

Studies in the medieval wine trade by Margery Kirkbride James, Clarendon Press, 1971