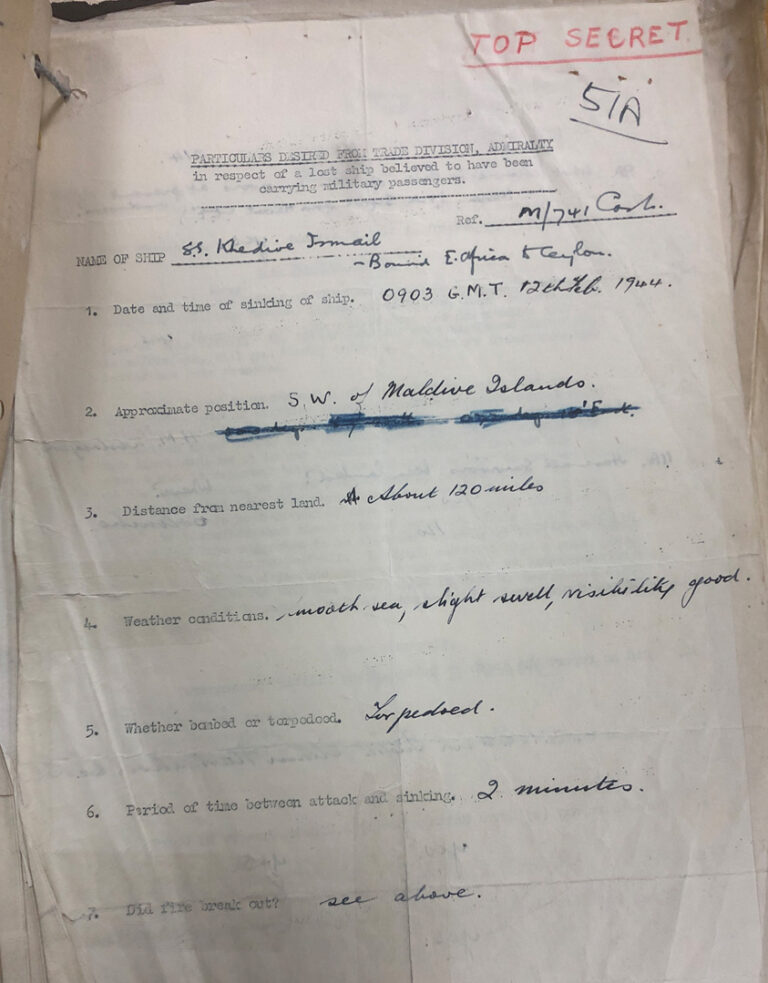

On the afternoon of 12 February 1944, travelling in a convoy from Mombasa to Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka), troopship SS Khedive Ismail was struck by two Japanese torpedoes just south-west of the Maldives. Hit directly in the vicinity of its engine and boiler rooms, the ship sank within just two minutes of the attack. Of the 1,506 passengers and crew on board, mostly military personnel, there were little more than 200 survivors.

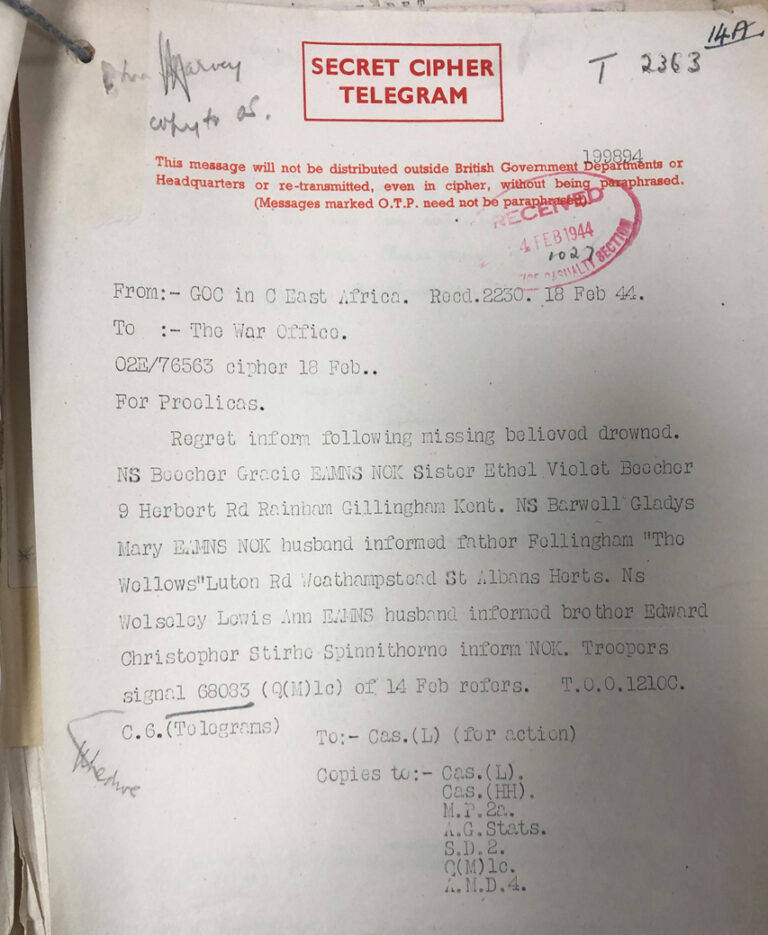

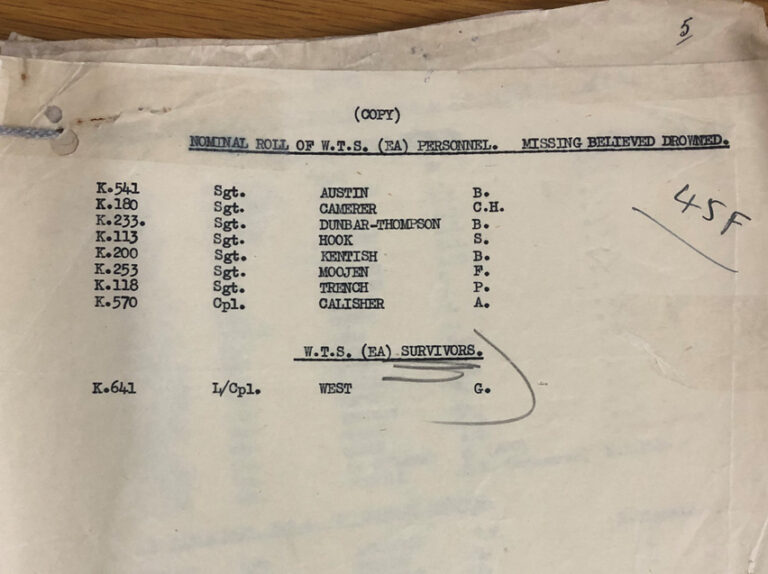

Seventy-seven of the victims were women, the vast majority of whom were enlisted in three of the key East African women’s services discussed in my previous blog. The breakdown of women killed was as follows: eight in the East African Women’s Territorial Service (WTS), 17 in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), one civilian and 51 nurses in both the East African Military Nursing Service (EAMNS) and Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS). These numbers add up to the worst loss of female service personnel in the history of the British Commonwealth.

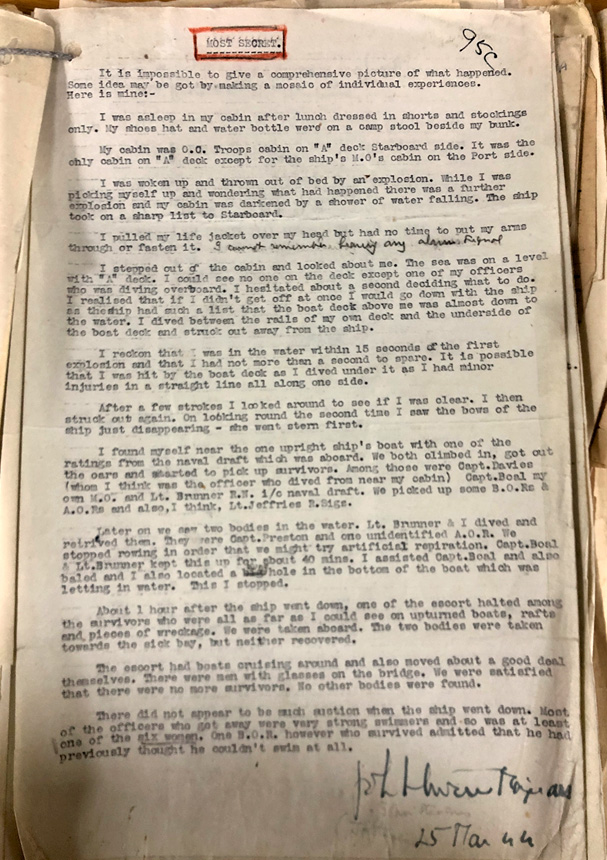

EAMNS nurse Phyllis Hutchinson was one of six female survivors on board. After the attack, she provided numerous statements to the War Office Casualties Branch. In her first account of events on 25 March 1944, she wrote:

‘I was woken up and thrown out of bed by an explosion. While I was picking myself up and wondering what had happened there was a further explosion and my cabin was darkened by a shower of water falling. The ship took on a sharp list to starboard … I reckon I was in the water within 15 seconds of the first explosion and that I had not more than a second to spare.’

Catalogue ref: WO 361/479

Less than a year later, on 21 January 1945, Phyllis provided the War Office with another statement. This time, rather harrowingly, she explicitly recalled the fate of her fellow nursing comrades:

‘Miss P Cashmore EAMNS somersaulted backwards into the gaping hole in the middle of the ship …

When deep in the water I saw the dead body of a fairly tall, slender girl shoot past me, I did not see her face but the figure was akin to that of Miss Clark Wilson …

Miss M J Littleton QAIMNSR and Miss Davies QAIMNSR were sunbathing on the deck a short distance away from me prior to the attack. I did not see them again.’

Catalogue ref: WO 361/479

These women, along with their fellow comrades, were undoubtedly extraordinary individuals. In juxtaposition with clearly defined gender roles at the time, many were serving far from home and taking up work that may not have been available to them prior to the Second World War. A large number of women were married and some even had children.

Using various records from The National Archives, it has been possible to piece together a more detailed picture for how two women in particular, of different ages, from diverse backgrounds, ended up together on SS Khedive Ismail. Tragically, neither survived.

Sister Grace Beecher, EAMNS

Born to British parents in Antofagasta, Chile on 16 February 1896, Grace Beecher was no stranger to overseas travel. Using incoming and outgoing passenger lists in series BT 26 and BT 27, she can be found making numerous long-haul trips to multiple destinations throughout her adult life. Her first appearance on any passenger list held at The National Archives appears to be February 1919. At the age of 23, Grace arrived from Chile, into the port of Liverpool, listing her intended permanent residence as England and occupation as ‘nurse’ (BT 26/651/135).

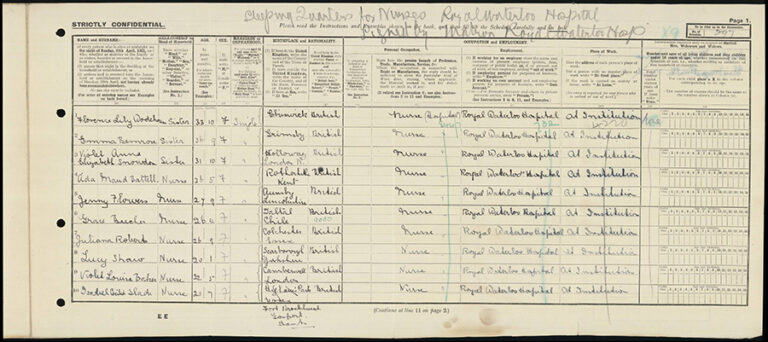

In the 1921 Census, she can be found training/working at London’s Royal Waterloo Hospital, living just a stone’s throw away on Coin Street with a number of other nurses (RG 15/1984). After becoming state registered in June 1924, she can then be traced to an outgoing passenger list just two months later, this time returning back to her country of birth Chile (BT 27/1050).

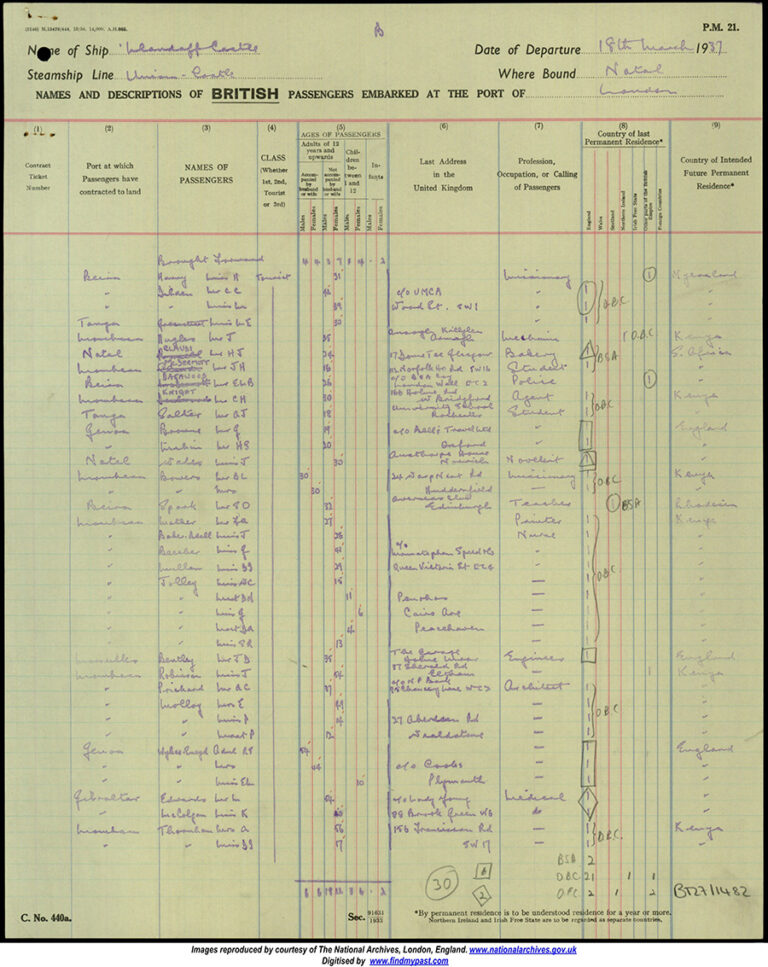

Over the following years, Grace made several trips back and forth to the UK. In March 1937 at the age of 41, she departed London for what was to be her final time, en route to Mombasa (BT 27/1482). She enlisted in the East African Military Nursing Service (EAMNS) in July 1940, and from that point onwards was eligible for military service in any part of Africa, or overseas. Prior to embarking on SS Khedive Ismail, Grace was with the 106 East Africa Section General Hospital.

Sergeant Barbara Kentish, WTS

Born in Lee, London during the spring of 1913, Barbara Kentish can be found in the 1921 Census living in Lewisham with her brother, two parents and the family’s servant (RG 15/2844).

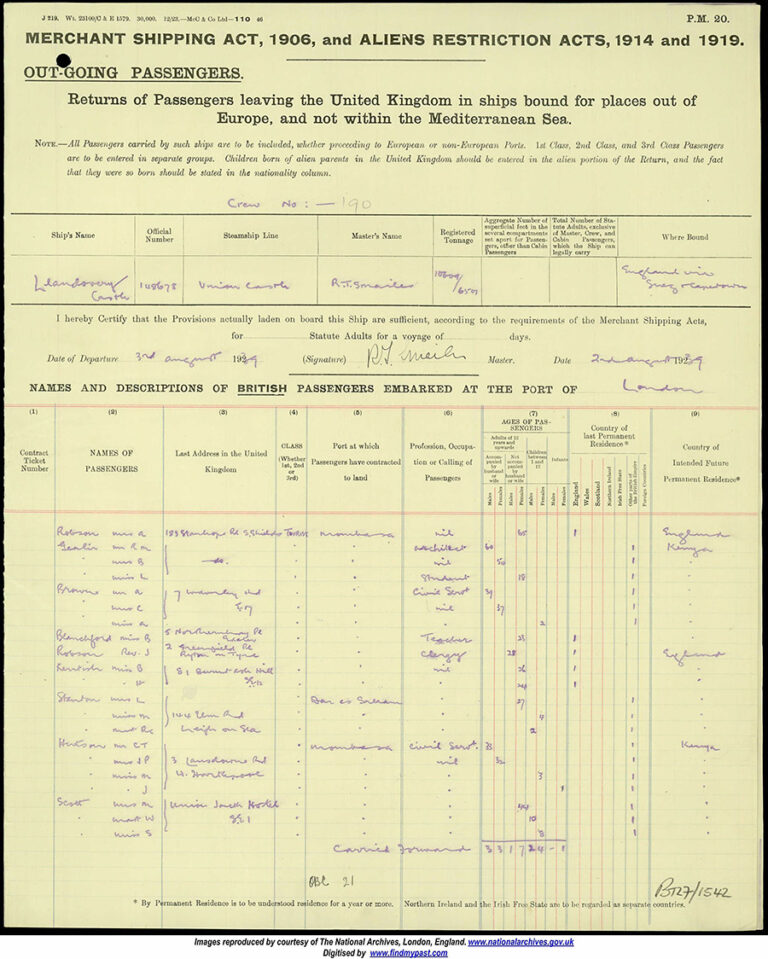

On 3 August 1939, exactly one month prior to Great Britain declaring war on Germany, Barbara’s name appears once again, this time in an outgoing passenger list, travelling from London to Mombasa (BT 27/1542). Accompanying her was a ‘Miss H. Kentish’, recorded as being just two years younger than Barbara and living at the same address. What is perhaps most interesting about this passenger list is Barbara’s stated intention to return to England, and what this suggests about how she ended up serving in the British army’s WTS.

Unlike Grace Beecher, Barbara and her companion had no obvious intention of remaining in East Africa. So, what were their motivations for travelling so far from home, just one month prior to the outbreak of the Second World War? Was it simply an ‘accident’ that Barbara remained, unable to return home? If so, her mention in multiple despatches certainly alludes to the fact she rose to the occasion.

Or was this Barbara’s plan all along? Until September 1941, the WTS was operating as an East African branch of the British First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), a unit closely affiliated to but not officially a part of the Armed forces. As the daughter of a solicitor, Barbara certainly fit the typically middle/upper-class profile of a member of the FANY. But given the fact that the unit did not encourage recruitment of British nationals living permanently in the UK, it’s difficult to say for sure. The only thing that does remain certain is the tragic circumstances leading to her death, and that of 1,296 men and women: brothers, fathers, mothers, sisters, sons, daughters and friends.

Less than 80 years later, the sinking of SS Khedive Ismail deserves to be remembered.

My late Father, Bill Hiscock, was a Royal Marine on board HMS Hawkins and witnessed the sinking. He proudly attended the 50th anniversary commemoration at the chapel of St Mary Le Strand in London and I proudly attended the 75th anniversary service on his behalf in 2019. At this latter service was a lady who’s Mother had been prevented from travelling on board the SS Khedive Ismail. The amount of WRN personnel had been over allocated by two so it was decided that the two junior WRNs would be left at Mombasa. Her mother was one of them.

If a service is planned for next year’s 80th anniversary I would be honoured to attend.

A service is planned for next year, but the date has not been finalised. The service will be at the WRNS Church, Mary le Strand

The account above that you record as the statement of Nursing Sister Phyllis Hutchinson is not hers. It is the statement of Lieutenant Colonel J. A. Stevens, the commanding officer of 301st Field Regiment, East African Artillery. He subsequently wrote an article about his experiences that may be found in The Royal Artillery Commemoration Book 1939-1945. In it he builds on the original statement. You will see that he refers to ‘my own MO’ (Boal) and records the names of other officers of or attached to his regiment.

Interestingly, the two nursing sisters of the East African Military Nursing Service that survived were both rewarded for their later work: Nursing Sister Margaret Joyce Garratt was made and A.R.R.C in 1946 and Nursing Sister Phyllis Hutchinson, was appointed M.B.E. in 1950 for her services with Queen Elizabeth’s Colonial Nursing Service in Nyasaland.

One slight correction to a name spelling,

it was Nursing Sister Margaret Joyce GARRETT who was one of the survivors. (I am her son)

I am leading a history project to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of WW2 based at St Michael’s Church, Ashton-on-Ribble, Preston. WRN Marie Elizabeth Breakell was among those killed in the Khediv Ismail sinking and is commemorated on our war memorial.

We plan to mount a memorial exhibition, produce a memorial volume and hold a memorial evening at Remembrance weekend 2025.

Any relatives within reach of Preston will be welcome to join us.

Visit the ‘St Michael and All Angels Church with St Mark’s Preston’ Facebook page for more information.