Many of you will no doubt have heard of, if not yet seen, the recent film Testament of youth (based on a best-selling book of the same name) which tells the story of Vera Brittain’s experiences during the First World War. Brittain was studying at a hard won place at Oxford University at the time war was declared. However, as men she knew and loved started to die, she felt that she needed to do something for the war effort and so joined the British Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) as a nurse. She, like many others, served in military hospitals both at home and abroad, tending to wounded soldiers, of whom there were soon to many to count……

But Vera Brittain was only one of thousands of women who enrolled into nursing services, such as the VAD, and military services, such as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS or Wrens) and the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) during the First World War. These women made a huge and important contribution to the war effort and their roles must not be forgotten. So, during Women’s History Month this March, here at The National Archives we are commemorating women’s achievement by holding a number of events. These events include a poetry reading, which gives voice to the experiences of ordinary women living through these extraordinary times, and a webinar which will help trace your ancestors in the women’s nursing and military services.

During our research for the webinar in particular, we came across a number of interesting stories that highlighted women’s roles in the war. These stories, we felt, were too good not to share! So here is selection, giving you a snapshot of the lives of just a few of the thousands of women serving their country in the First World War…..

Nursing was one of the most common yet life changing duties undertaken by women during the war. They often worked very close to the front line, confronted by the horrific medical realities of conflict. We hold many records relating to such nurses, which can take many different formats, depending on the organisations the women served with.

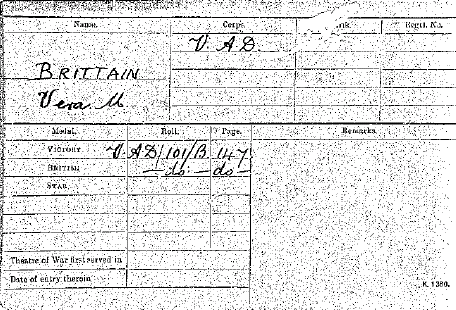

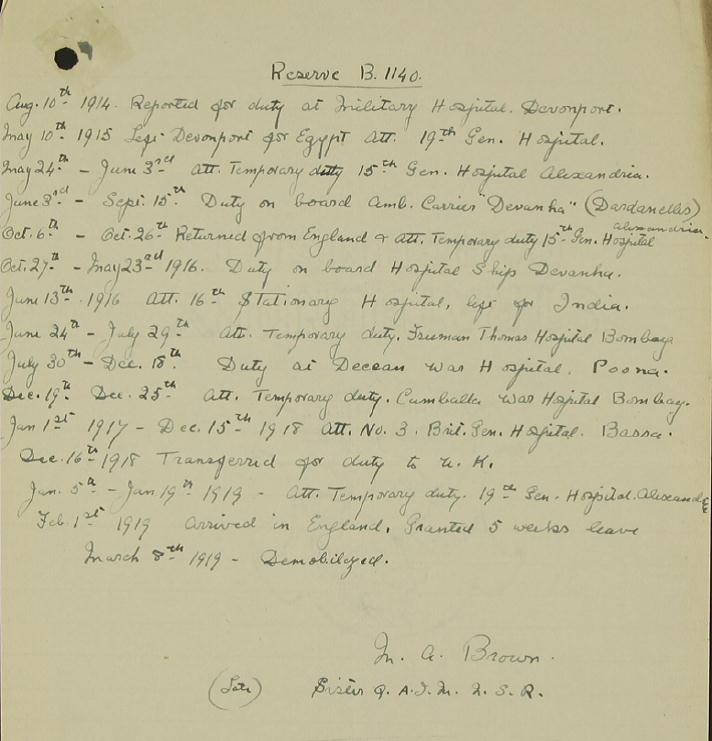

One of the key record series is WO 399 which relates to the service records of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) and the Territorial Force Nursing Service during the First World War. These records often hold a wonderful level of detail, and can include character statements, information about the surrounding families’ status, and profession as part of the assessment.

We have the case of Mary Ann Brown, WO 399/1023, who served in the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve): her service record follows her from Devonport in the UK, to the General Hospital at Alexandria, in Egypt. This is followed by a duty on the hospital ship Devantia, a stationing hospital in India, The Freeman Thomas Hospital in Bombay and No. 3 Bri General Hospital in Basra, where she worked until March 1919. She travelled widely, as many other nurses would have done. This must have been incredibly eye opening as most would have never been abroad before, yet they would now be shipping off to different theatres of war across the globe, experiencing previously unimaginable climates and cultures.

The records in the series MH 106 can also be very insightful despite being a very small selection of medical sample records. They cover a variety of places female nurses would have been serving in, and a number of boxes additionally relate to women’s services, including nurses and VADs, but also services such as the WRAF. A particularly interesting example can be found in the case of Alice M Pym (MH 106/2208),who served in the Queen Mary Auxiliary Army Corps (QMAAC) and who was essentially suffering from shellshock. As part of our Files on Film competition this record inspired the following film.

Nursing positions, however, were not the only roles women undertook. Auxiliary military services in the army, navy and RAF were first established during the First World War and we hold thousands of records relating to individual women who served in these services – although record survival rates often depend on which service.

A particularly good example we found was an officer in the Women’s Royal Navy, Maud Massey Cottrell (ADM 318/5). What was particularly heart-warming about this example was that Massey requests to serve with her friend and work with ‘Miss Bell under her, as they have worked together for so long’. Hildred Nora Bell also became a WRN Officer on 15 January 1918 (ADM 318/18). Her records show that she too stated that she was ’very anxious to work with Miss Cottrell’. The two, it seems, were inseparable. Massey wrote to the assistant director of training to request one week’s leave for Miss Bell and herself between finishing their training and ‘taking up any new duties we may be appointed’, and rather than post two separate letters to the two women, it is also asks Miss Cottrell to ‘kindly tell Miss Bell or show her this letter’.

My favourite detail which highlights the friendship between the two was the probationary officer’s report; Hildred’s was completed by Ida Thomson. In response to the question ‘would she do better working under another officer?’ Ida answers ‘I can hardly say. She and Miss Cottrell are always together and Miss Bell seems a little merged in Miss Cottrell’.

Excerpt from the personal files for officers of the WRN: Miss Hildred Nora Bell, catalogue reference: ADM 318/18.

You might think that the regimented military lifestyle applied only to the men and their units. But the war diaries of the WAAC (later Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps) in WO 95/85 reveal that this was not the case. The women were subjected to equally stringent inspections and rules, such as ensuring their uniform was worn correctly; they were punctual for work and roll call, and did not meet officers without permission!

Whilst the majority of women most likely followed these rules, the war diaries highlight some excellent examples where women brazenly flouted these regulations. One of our favourite examples is of two workers who on the 25 December 1917 ‘had remained out the previous evening without permission, had taken too much to drink, and had returned to their unit at 11:30pm and 1:20am’. Clearly they were getting into the spirit of Christmas! However, their superiors were less than amused and the two were ‘thoroughly investigated’.

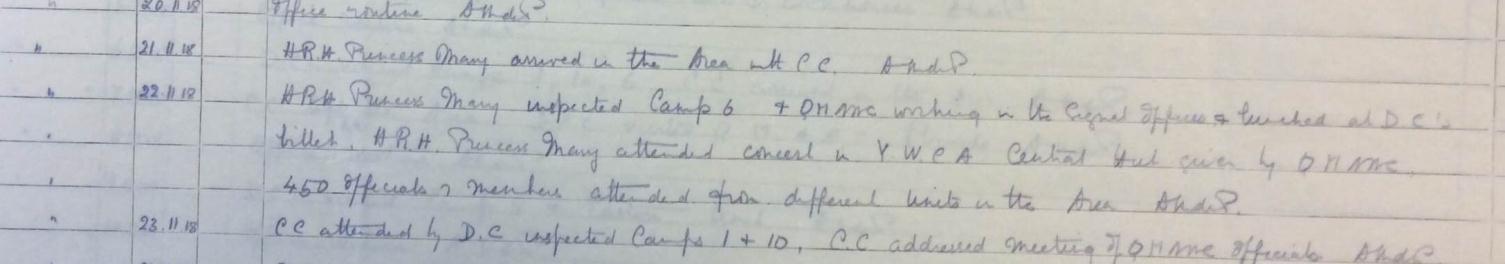

The war diaries give a great sense of the daily lives of women serving in the WAAC, including various dances, fancy dress parties (sometimes ‘with men clerks…who entertained the women clerks’), concerts, hockey matches and swimming competitions. They also mention noteworthy events such as the arrival of Princess Mary, whose arrival allowed for ‘450 officials and members from different units to the Area’ to watch a concert performed by the QMAAC. The diaries can offer a unique and interesting insight into the lives of women in the WAAC/QMAAC throughout the duration of the war until their demobilisation.

Excerpt from the war diary for Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps: Area Controller Havre Area, 1917 June – 1919 September, catalogue reference: WO 95/85.

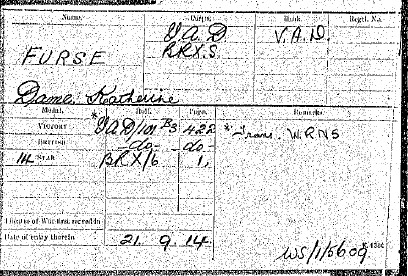

As we know, Vera Britten among some 23,000 others, served as a nurse in the British Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD). This service allowed women to serve in many capacities in both theatres of war and on home soil. Duties for VAD volunteers were quite typical of female service roles of the era and could include canteen work, cleaning and cooking, as well as nursing. In fact, it wasn’t until a small group of VADs proved themselves under fire, late in the first year of war, that they were permitted to nurse at all.

The story goes that a VAD section leader took two canteen workers to France in October 1914, where they came under enemy fire and were all pressed into service in an emergency hospital. These three extraordinary women acquitted themselves with such calm dignity in terrifying and unfamiliar circumstances, that from then onwards VADs were permitted to take official first aid training and join overseas military hospitals.

The leader of this band of brave VADs, the first in France during the First World War, and Commander in Chief of the Joint Women’s VAD Corps, was Dame Katharine Furse. Dame Katharine’s campaign medal card can be seen below, revealing that she received the Victory Medal, British War Medal, and 1914 Star before she took up a post as first head of the WRENs in 1917. This is just one example of the bravery and determination of women to serve their country during the First World War. Furse eventually went on to be awarded a GBE in 1917 and a Royal Red Cross for her First World War service.

Furse’s is a particularly glamorous career in women’s services, however she and every one of the women who gave their time, and in a few cases their lives, still exist in some tangible way in archival records. These women of the First World War experienced the same horror as the brothers, sons, uncles, fathers and friends they were losing everyday on the front, just in a slightly different way. There are so many avenues still to explore and so many stories still to be told. As you can see, women’s experiences of this conflict were diverse and as meaningful today as they were 100 years ago.

We hope we have helped to begin unearthing these lives and stories and also have shown that there are still many more out there for you to find – long gone, and now not forgotten. If you would like to continue the journey and join us as we continue to explore and remember these extraordinary women and their experiences then please see our Women’s History Month events. War girls: poetry and prose by women in the First World War sees a moving reading from an anthology of First World War poetry, written by the women living through the conflict. We pair our factual original documents with emotive poetry of the era, bringing past and present, research and prose together. Our webinar Tracing your ancestors: women in the military services during First World War will explore the full range of First World War women’s services and identify the best places to start searching our records for them.

We hope to see you there!

Linked from the National Archive, in my search for items related to some of my studies. Such a big subject this

Thank you for your comment Chris, it is indeed a vast and diverse research subject – there is so much we found but couldn’t fit in! We are hoping to show how insightful and interesting the records are, and that there are plenty of service women’s stories still to be told. If you would like to know more about these records and how to find them then please consider logging in to our online webinar ‘Tracing your ancestors: Women in the Military Services during First World War’ on Monday 16 March at 16:00. We will be explaing how to access these records and exactly what we hold in relation to each service.

[…] A Woman’s War 1914-1918 […]

Thank you for your very interesting and helpful blog. Through you I have been able to locate the medal index cards for two women, one a VAD and the other an English woman who served with the French Red Cross. Both received the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. I have been trying all combinations of the names on Ancestry.com with no results. Your blog gave me the WO372/23/4814 roll number which enabled me to find these two women volunteers. Thank you very much…..Mike