This autumn sees the long-awaited broadcast of the dramatisation of Hilary Mantel’s final book in her Wolf Hall trilogy, a notable event for those of us fascinated by the Tudor period. It is being released in the UK by the BBC over six Sunday evenings, starting on 10 November.

Back in 2015 when the BBC showed the first series, I identified documents that demonstrated how Mantel used the historical record to inform her interpretation of Thomas Cromwell’s life, using his surviving correspondence. Here, I try to do the same for his final years.

Be aware that this blog post includes plot spoilers, so do not read if you do not already know how the story of Thomas Cromwell unfolds.

1. Writing to a sympathetic Cromwell?

The first episode (Wreckage) starts with the execution of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII’s marriage to Jane Seymour. A major theme is the status of the Lady Mary – Henry’s daughter by Katherine of Aragon – who has refused to accept that her parents’ marriage was now judged to be invalid and that her father was head of the Church of England.

The major holdings of historical documents relating to the reign of Henry VIII are summarised in the publication Letters and Papers…of the Reign of Henry VIII, which can be read on British History Online. On 1 June 1536, we can find one of several letters from Mary to Henry VIII submitting herself to his mercy. There are many letters from her to Cromwell as well, indicating that he did indeed play a large part in advising her at this perilous time in her life.

However, the letter I’ve decided to highlight is one sent to Cromwell by the Duchess of Norfolk, who is mentioned in passing in the first episode and again in episode three. The TV series focuses on Cromwell’s relationships with several women. In many cases, it is impossible for us to know how close those relationships were, but the correspondence that does survive indicates that some women of the Tudor court saw Cromwell as a potentially sympathetic ally and their best way to seek the favour of the King.

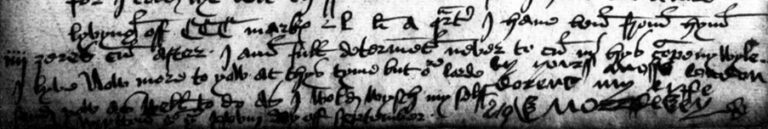

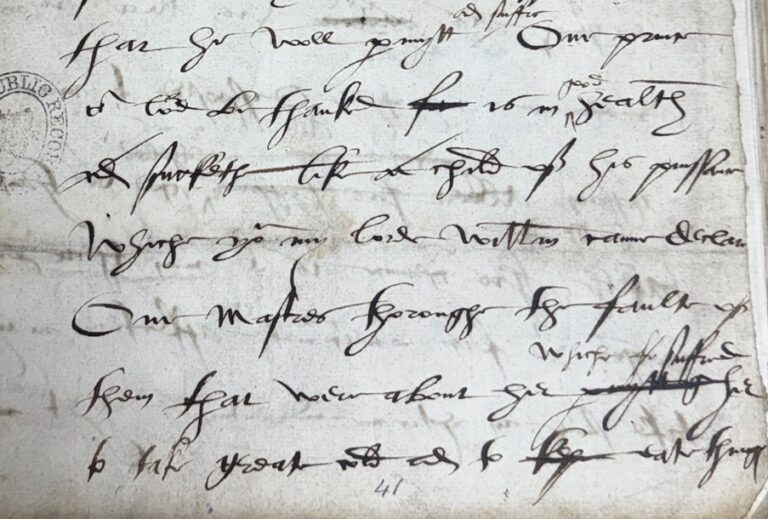

In episode one, Mary, bullied by the Duke of Norfolk, snaps back at him that he does not respect women and beats his wife. In a letter to Cromwell, dated 28 September 1536, the Duchess of Norfolk hints at this back story by writing that she will have been separated from her husband for four years at Easter and that she is determined never to be in his company while she lives. This is one of a series of letters in which she asks Cromwell to intercede with the Duke to help her financial situation.

2. Letter referring to a ‘secret’ matter

In episode two (Obedience), we see Cromwell’s continuing devotion to his late master, Cardinal Wolsey, resulting in a visit to Wolsey’s illegitimate daughter, who is a nun in Shaftesbury Abbey.

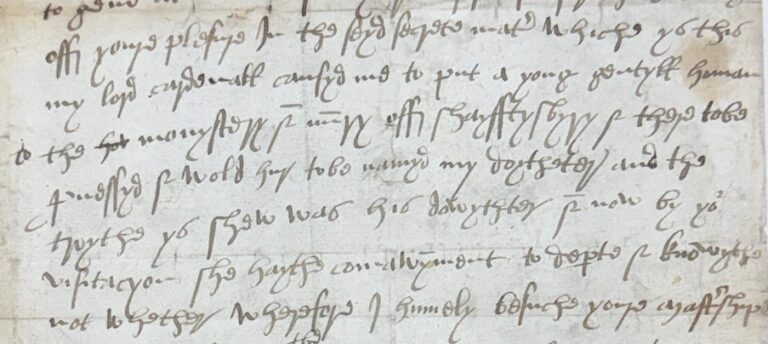

We do not know if Cromwell ever met her in reality, but he was certainly aware of her. This letter to him from a John Clasey, dated August 1535, refers to a ‘secret’ matter: ‘My lord Cardinal caused me to put a young gentlewoman into the nunnery at Shaftesbury, there to be professed in my name, though she was his daughter. She is now commanded to depart by your visitation and knows not whither.’

Dorothy Clansey, who is thought to be the same nun, was able to remain at Shaftesbury until it was dissolved in 1539, whereupon she received an annual pension of £4 13s 4d, authorised by Cromwell.

3. ‘The Queen thanks you for the quails’

Episode three (Defiance) sees the Lincolnshire Rising and Pilgrimage of Grace as a significant threat to Henry VIII’s reign. We have extensive records on these events, but the focus of the TV series remains in London, where we see the pressure upon Jane Seymour to become pregnant and the joy of Henry VIII when she does.

One scene starts with a mention of the fat quails sent by Lord Lisle, which Jane is greatly enjoying. These birds are the topic of several letters, as the King was anxious to supply his wife’s needs at this time. Lisle was the Lord Deputy of Calais and, as Edward IV’s illegitimate son, was Henry’s half-uncle. His family’s extensive correspondence remains in the State Papers having been forfeited at his attainder in 1540.

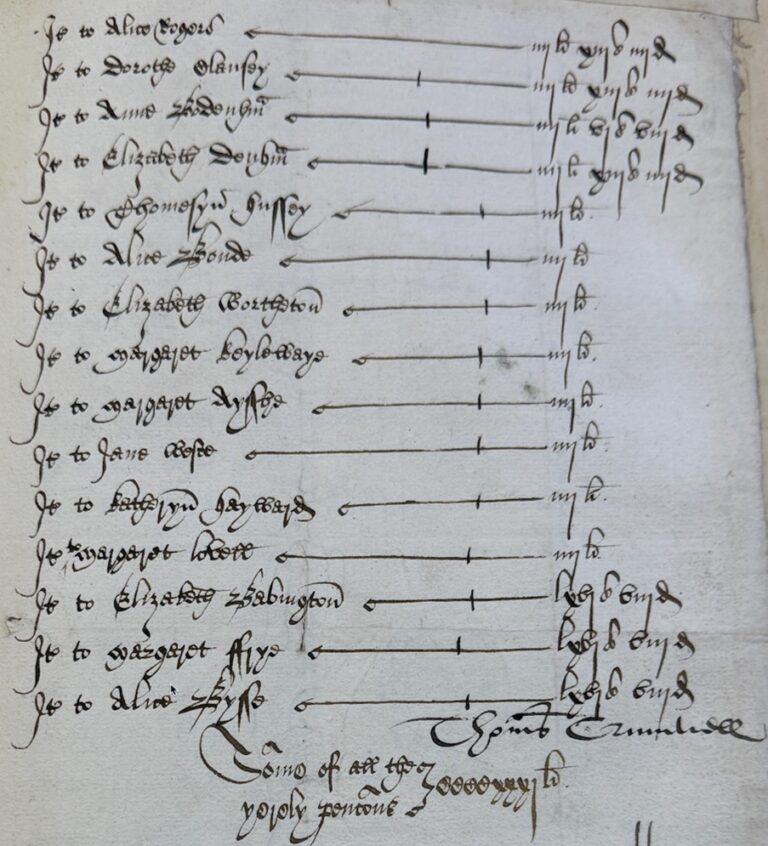

This letter of 17 July 1537 to Lord Lisle from his agent, John Husee, starts ‘The Queen thanks you for the quails. Those sent hereafter should be fat, or they are not worth thanks’ and then later mentions that, while eating them, the Queen had been persuaded to take one of Lisle’s daughters into her household, implying that the gift had directly resulted in additional royal favours.

An earlier letter of 23 May 1537 from John Husee to Lisle states that Sir John Russell ‘had written his Lordship two sundry letters, by the King’s express commandment, for fat quails for the Queen. He wishes two or three dozen sent at once, and killed at Dover, and afterwards 20 or 30 dozen. Will speedily see those sent by land conveyed to Hampton Court. If there be no fat ones at Calais, Lisle is to send with all speed into Flanders for them.’ It obviously helped to have a King’s power and authority when satisfying pregnancy cravings.

4. The death of Jane Seymour

Episode four (Jenneke) sees the welcome birth of a prince in October 1537, sadly followed by the death of Queen Jane a few days later. A week later, Cromwell wrote to England’s diplomats in France, Lord William Howard and Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, requesting them to inform the King of France that though the Prince is well and ‘sucketh like a child of his puissance’, the Queen, ‘through the fault of them that were about her which suffered her to take great cold and to eat things that her fantasy in sickness called for, is departed to God’.

Cromwell wasted no time in raising the subject of Henry VIII’s next marriage – his fourth – and asked the agents to investigate the French king’s daughter and Madame de Longueville (Mary of Guise, later wife of James V of Scotland) as potential brides.

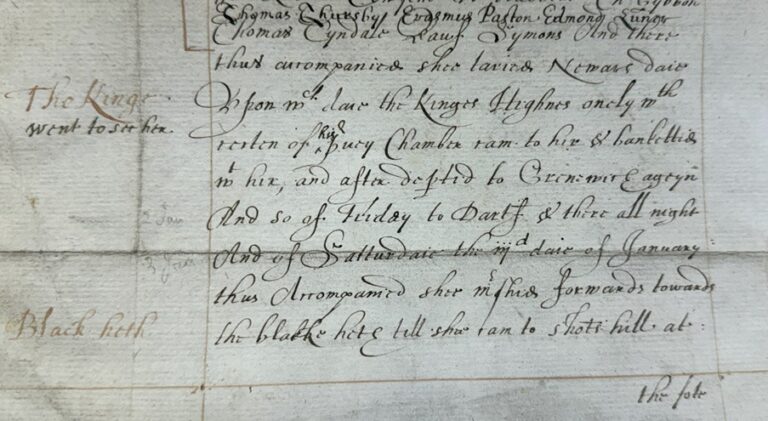

5. Tracking Anne of Cleves’ journey to England

Episode five (Mirror) will see Cromwell’s negotiations for a bride to support England’s diplomatic needs result in the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII to Anne of Cleves. This formally laid out document, with headings in gold ink, tracks the journey of Anne of Cleves to England. On New Year’s Day 1540, the King unexpectedly came to meet her at Rochester with members of his Privy Chamber. He banqueted with her and then returned to Greenwich. His disappointment in his bride was to resonate throughout the court and bring about Cromwell’s fall from grace.

6. Thomas Cromwell’s downfall

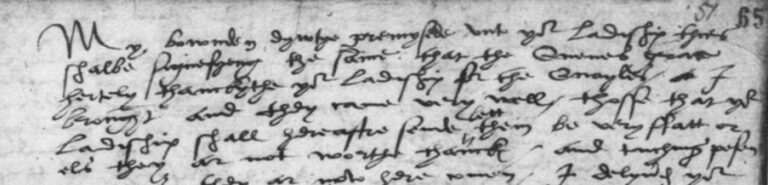

Episode six (Light) will see the end of Thomas Cromwell’s rise to power. Many of the things we know about the Tudor court were not recorded in writing by English courtiers, who were, after all, able to communicate face-to-face, but by foreign diplomats sending detailed reports back to their European masters.

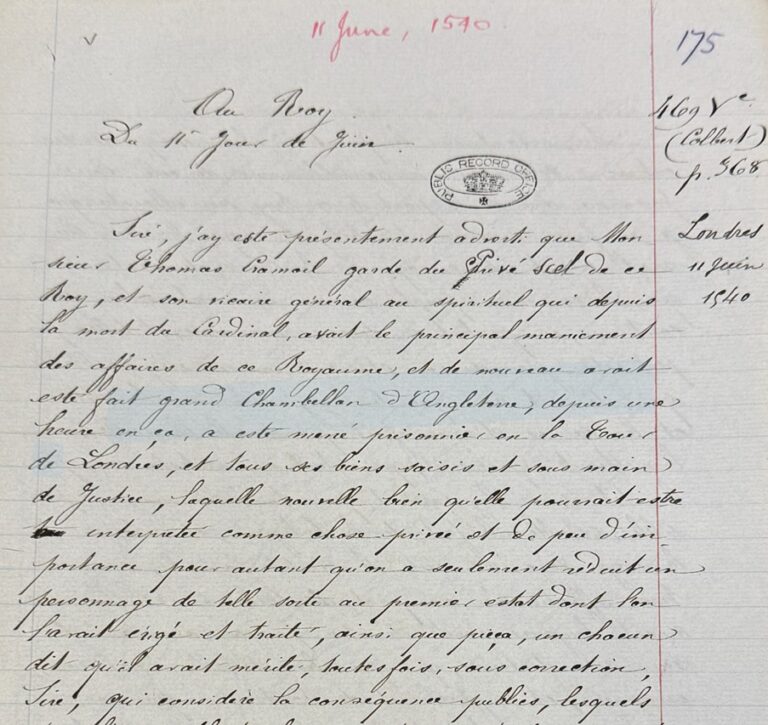

The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, wrote to King Francis I on 10 June 1540 with the breaking news of Cromwell’s arrest:

‘I have just heard that Thomas Cramvel, keeper of the Privy Seal and Vicar-General of the Spiritualty, who, since the Cardinal’s death, had the principal management of the affairs of this kingdom, and had been newly made Grand Chamberlain, was, an hour ago, led prisoner to the Tower and all his goods attached. Although this might be thought a private matter and of little importance, inasmuch as they have only reduced thus a personage to the state from which they raised him and treated him as hitherto everyone said he deserved, yet, considering that public affairs thereby entirely change their course, especially as regards the innovations in religion of which Cromwell was principal author, the news seems of such importance that it ought to be written forthwith.’

Charles de Marillac

We have a transcript of Marillac’s letter among our collections of diplomatic correspondence copied from European archives in the 19th century.

The meticulous costumes, sets and lighting of the Wolf Hall: Mirror and the Light TV series – as well as the language of Mantel’s books – have provided us with a bridge to a partly real and partly imaginary world, underpinned with knowledge which has come from archival records. Everyone is welcome to visit The National Archives to see related documents themselves and thereby to experience a first-hand connection to the men and women who have so fired our imaginations.

I enjoyed the books so much that I have reread them and could not see the wonderful actor chosen as my imagined Cromwell. The production itself is beautifully done of course BBC, but I am unable to see the final chapter due to limited TV. Mandel brought me further into histories and I credit her with sharpening my interests. Some lines always stay with me as i look at the ruling powers. I am saving all three books for my grandaughter.

I’m really enjoying this

If ever I could meet a figure from the past it would be Thomas Cromwell, scary. Manipulative, clever beyond belief, yet could have a kind heart. I think Hilary Mantel was in love with Cromwell. I Just watched episode 5 and of course we know Cromwell’s end but I am still anxious . Crazy I know Mark Rylance brilliant and though Damien Lewis is also brilliant it’s Mark Rylance I think that outshines the whole cast. I read all three books, and though we waited 5 years for the publication of Tge Mirror and the Light I found it disappointing. However the BBC series has made up for it. Amazing!

I have found this latest email fascinating. Next time I’m in London I would love to come and visit the National Archives. I love history and have read all three of Mantel’s books. I’m thoroughly enjoying the televised version as well and I find Cromwell’s character so complex. I recently read that Cromwell’s grandfather came from a village in Nottinghamshire and moved to Putney where he got married. I’m going to visit the village in Nottinghamshire as it’s close to where I now live.

I read all three books and loved them (read A Place of Greater Safety also by Mantel, brilliant) and have re-watched the BBC Wolf Hall three times. This series has me feeling so sad for Cromwell, even though I have known the outcome since school.

I am very much enjoying The Mirror & The Light, and in awe of the acting. One matter that does rather spoil the authenticity is to keep being brought back to reality by the use of Stuart and later furniture and furnishings, obviously because actual Tudor furniture is so rare, and lacking often in elaborate upholstery. Victorian and later parts of Hampton Court Palace also keep appearing although of course designed to be in keeping with the earlier bits of Wolsey’s great edifice. Probably this is all inevitable but it might give a slightly false impression of how things actually looked in the day.

I also have greatly enjoyed and admired the whole production of The Mirror and the Light, but am glad to have read Mantel’s trilogy before watching the TV episodes which are all sombre and unrelieved by humour. I will look forward to the viewing stats and suspect they may be modest. But I strongly recommend

reading Diarmid McCulloch’s fine academically researched biography ‘Thomas Cromwell – A Life’ which greatly influenced Mantel and led to friendship between these two fine authors.

It was Fascinating to read ,view and revisit this part of our history. I , like many having visited many of the places featured in the series , when young , and really not appreciating the events that shaped the Country , but now in latter years can see the power play and intricacies of how things were . An astonishing accomplishment in this series , thank you so much for this .