I’ve recently been undertaking some research into the signing of the Atlantic Charter (14 August 1941), which set out the post-war aims of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill undertook a long and daring journey by ship to meet US President Franklin D Roosevelt in Placentia Bay, off Newfoundland, and the Charter was the result of this significant conference. When I read about the fascinating details of this journey, I reflected that this was by no means the only hazardous journey undertaken by Churchill during the war. As Professor Christopher H Sterling has written, ‘Churchill travelled farther and more extensively than any other wartime leader’ (see footnote 1).

Churchill preferred to fly, as it obviously saved time, but he also undertook several voyages by sea during the war. In July 1941, Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s close advisor, had informed Churchill that Roosevelt would like to meet him. This was promising news for Churchill, whose underlying hope was that America would get more involved with the war.

A Prime Minister’s Office file shows that Churchill wrote to King George VI on 25 July, informing him of the invitation to meet President Roosevelt ‘somewhere off Newfoundland’. Churchill scrupulously observed wartime protocols by formally asking the King’s permission to leave the country:

‘The Cabinet strongly approve my going, and if your Majesty would graciously consent, I should propose to sail from Scapa on the evening of the 4th… I hope Your Majesty will feel that all this is in accordance with the public interest.’

The King replied, the same day, using these touching words:

‘I do not think that one would be likely to find a better moment for you to be out of the country, though I confess that I shall breathe a sigh of relief when you are safely home again!’

Catalogue ref: PREM 3/485/6

On 1 August John Colville, Churchill’s Private Secretary, wrote in his diary that Churchill was very enthusiastic about the prospect of meeting Roosevelt – that the Prime Minister was ‘as excited as a schoolboy on the last day of term’ (footnote 2). On 4 August the Prime Minister and his retinue boarded the battleship HMS Prince of Wales at Scapa Flow, the natural harbour in the Orkney Islands, Scotland.

The telegrams which were sent by Churchill tell an interesting story. On 4 August he wrote to Roosevelt:

‘We are just off. It is twenty-seven years ago today that Huns began their last war. We must make a good job of it this time. Twice ought to be enough. Look forward do much to our meeting. Kindest regards’.

Catalogue ref: CAB 120/24

The use of the derogatory word ‘Huns’ to describe the Germans obviously needs to be viewed in the historical context.

Churchill did, of course, prepare for the Atlantic Conference during the journey (codename ‘Riviera’). However, he had lots of time on his hands: ‘Churchill had been more idle on the voyage than on any day since he became Prime Minister’ (footnote 3). The details of how he spent his time on board the battleship are fascinating. He read ‘Captain Hornblower R.N.’ by C S Forester (one can imagine him rejoicing in the exploits of this swashbuckling hero). He also played backgammon, though he fared badly, losing seven guineas in a game with Harry Hopkins.

Churchill and his party watched films every evening in the Wardroom which, according to historian and biographer Andrew Roberts, included Donald Duck’s ‘Foxhunting’ and Laurel and Hardy’s ‘Saps at Sea’ (this ‘delighted’ Churchill) (footnote 4). Another film which Churchill watched again and again was ‘That Hamilton Woman’ (also known as ‘Lady Hamilton’). Against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars, the film tells the story of the rise and fall of Emma Hamilton, the dancer and actress (played by Vivien Leigh) who became mistress to Admiral Horatio Nelson (played by Laurence Olivier). ‘That Hamilton Woman’ framed Britain’s battle against Napoleon in terms of resistance to a world-dominating dictator, drawing obvious parallels with the situation in 1941. It moved Churchill to tears.

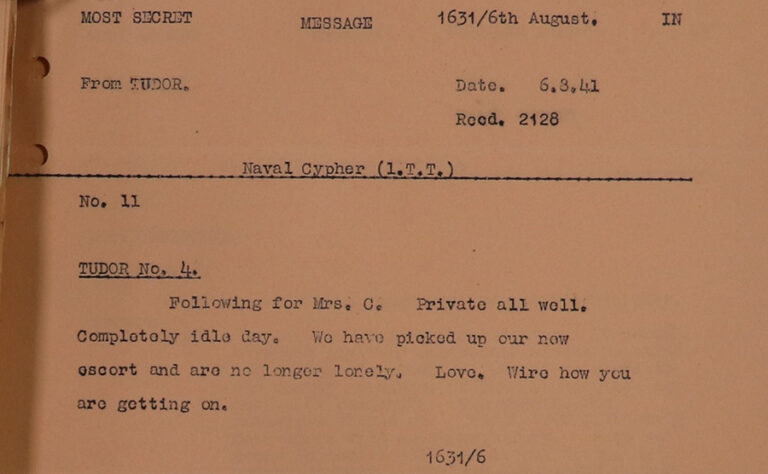

On 5 August, the Prince of Wales had to leave their destroyer escort behind due to very rough seas, and proceed unescorted, but fortunately this situation was rectified in the course of the next day, as confirmed by this telegram from Churchill to his wife, Clementine, of 6 August:

‘Following for Mrs C. Private all well. Completely idle day. We have picked up our new escort and are no longer lonely. Love. Wire how you are getting on’.

Catalogue ref: CAB 120/24

I find that telegrams within files, in many cases, hold a particular fascination, and this is a great example. It is very concise, but there is actually a great deal of information being conveyed by Winston to Clementine in those 29 words, including the personal touches. Part of the fascination lies in seeing those personal touches in such an official looking Naval Cypher message, marked ‘Top Secret’. Incidentally, I think ‘Tudor’ was the code name given to the operation of the outward voyage – or maybe it applied to Churchill himself, I’m not quite sure.

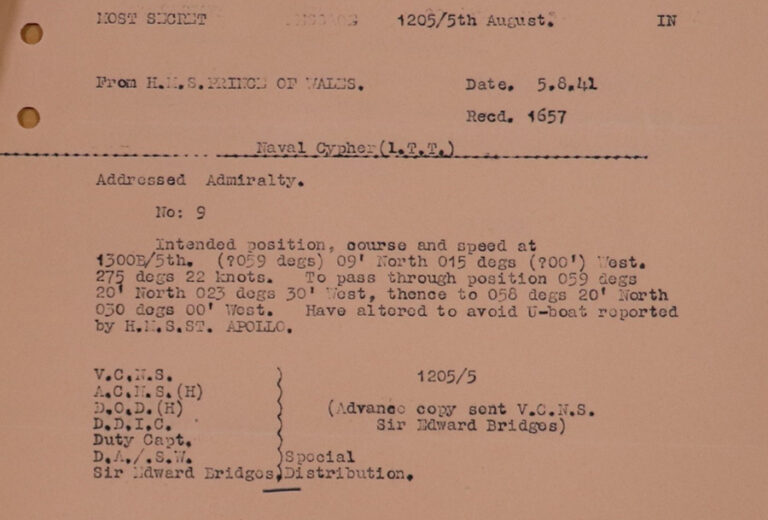

As well as coping with heavy seas on 5 August, HMS Prince of Wales also had to change course when a U-boat was sighted, as can be seen by this message below from the battleship to the Admiralty. It contains a great deal of technical nautical information but the crucial line is: ‘Have altered to avoid U-boat reported by HMS St. Apollo’.

The journalist H V Morton was on board the Prince of Wales and wrote a specially commissioned article entitled ‘Mr Churchill’s Secret Voyage’, the text of which appears in a telegram within a PREM file. He wrote:

‘On Saturday morning, August 9th, a grey, misty land came into view on the edge of the sky. Waves (? broke) on deserted beaches’.

Morton writes that the Prime Minister was on the bridge at 06:00 looking out for the escort of American destroyers that would meet the battleship, and Churchill immediately saluted them when they came into sight. Morton continues:

‘Grey ships of American fleet lay at anchor in a wide bay. As the HMS Prince of Wales steamed past them the band of Royal Marines crashed into “The Star-Spangled Banner”, and from the deck of [the] American flagship came the answering strains of “God Save the King”. Upon her deck, surrounded by naval and military officers, was the tall figure of the President of the United States’.

Catalogue ref: CAB 120/22. It is a well-known fact that President Roosevelt often hid his partial paralysis.

The story is continued in my second blog post on ‘Winston Churchill’s Secret Voyage: The Atlantic Charter’.

Footnotes

- Getting There: Churchill’s Wartime Journeys – International Churchill Society online article by Christopher H Sterling, May 1 2013

- ‘The Fringes of Power, Downing Street Diaries 1939-1945’, John Colville (Phoenix, 2005), p. 368

- ‘Churchill’, Roy Jenkins (Pan Books, 2001), p. 663

- ‘Churchill: Walking with Destiny’, Andrew Roberts (Allen Lane, 2018) p. 672

Fantastic essay. Eager to read part 2

The most eloquent begging bowl of British history. The photo of Winston grim-faced, pacing the afterdeck of the Prince of Wales is almost a metaphor of how alone Britain stood. My uncle told me of what a troubled passenger he was on that westbound voyage

A most illuminating essay on this vital meeting from which emanated ‘The Atlantic Charter’.

Mr. Dunton is to be most congratulated on this work, which is very easy to read.