Seventy-five years on, as we reflect on images of Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, addressing a joyous thronging crowd at Whitehall, and standing before the jubilant masses with the Royal Family on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, it is curious that few ever enquired as to the whereabouts of Clementine Churchill, his devoted wife who supported him during five years of wartime leadership.

Many would be surprised to hear that ‘Clemmie’ was not actually in London on 8 May 1945, while her husband was leading the nation in its celebration of Allied victory in the Second World War. She was in Moscow at the close of a twice-extended whirlwind tour of the Soviet Union. Moreover, her visit was an astounding success, and had come at a moment when Anglo-Soviet relations had reached a nadir. So what brought Churchill’s wife to Moscow?

The Foreign Office FO 594 series contains a number of documents, including personal minutes and items of telegram correspondence, that were exchanged by Churchill, the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, and Britain’s Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Sir Archibald Clark-Kerr. These communications concerned the visit of Mrs Churchill to the USSR, from 2 April to 11 May 1945, in her capacity as Chairwoman of the British Red Cross ‘Aid to Russia Fund’, an initiative upon which she had laboured for much of the duration of the wartime alliance.

Clementine Churchill volunteered for the British Red Cross Society at the beginning of the war, and became one of the organisation’s most active and high-profile serving members. In October 1941, three months after the invasion of the Soviet Union, she was appointed by the British Red Cross to head their Aid to Russia Fund. Throughout the course of what the Soviet peoples would call ‘the Great Patriotic War’, this scheme provided the citizens of war-torn and besieged Soviet cities, such as Stalingrad and Leningrad, with supplies of clothing and medical aid. However, it was the fundraising activities of ‘Mrs. Churchill’s fund’ that provided the most tangible evidence of the good will of the British people towards the people of the Soviet Union. Within a year and a half of its establishment, the Aid to Russia Fund raised £3 million[ref]David Reynolds and Vladimir Pechatnov (eds.), The Kremlin Letters: Stalin’s Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (London: Yale University Press, 2018), pp. 230-1[/ref].

From across Britain, the Commonwealth and the Empire, donations were received from people of all levels of society, from the King and Queen, who donated £1,000 in the first week of the scheme, to ordinary wage earners who committed to a penny-a-week subscription. Large donations were raised through one-off submissions from generous benefactors, including Lord Nuffield’s £50,000 cheque, but there were also the offerings of thousands of community groups and organisations which undertook a variety of fundraising efforts.

All over the nation, groups and associations came together to organise an assortment of fundraising activities, including town flag days and festivals, school pageants, sports tournaments and music recitals; knitting and baking groups gave proceeds from the sale of their goods, while collections would be held by factory workers, hospital matrons and even soldiers.

By the close of the war, the people of Britain and the Empire donated more than £7 million to the fund. From this, £4 million worth of medical supplies, including 11,600 tons of medical aid and clothing, 2,000 tons of powdered medicines and 22,000 units of medical equipment, were purchased and shipped to the USSR[ref]Claire Knight, ‘Mrs Churchill Goes to Russia: The Wartime Gift Exchange between Britain and the Soviet Union’ in Anthony Cross (ed.) A People Passing Rude: British Responses to Russian Culture (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2012), p. 255[/ref].

The stunning success of the Aid to Russia Fund, owing to the generosity of the British public, was a major coup for British diplomacy and was useful for difficult moments in Anglo-Soviet relations, especially at times when Britain struggled to maintain a steady supply of war materials to the USSR. For their part, the Soviet government was profoundly grateful to the Churchills for personally spearheading such charitable efforts. It was for this reason that it decided to extend an official invitation for Clementine Churchill to tour the Soviet Union and witness, first-hand, what her fund had achieved[ref]Clementine Churchill, My Visit to Russia (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1945), p. 15[/ref].

Initial arrangements for Mrs Churchill’s visit would be communicated by the Foreign Office to the British Embassy in Moscow on 9 March. The telegram informed the Ambassador, Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, that Mrs Churchill, accompanied by Miss Mable Johnson, Secretary of the Aid to Russia Fund, and Grace Hamblin, her Private Secretary, expected to arrive by air in Russia sometime before April 2 for a month-long trip. As a guest of the Soviet government, they were informed that arrangements for Clementine’s accommodation would be made by her hosts, but that a member of the British embassy staff should be made available as her advisor. The telegram also added: ‘Generally, her interpreter will be Russian’ (FO 954/26C/567).

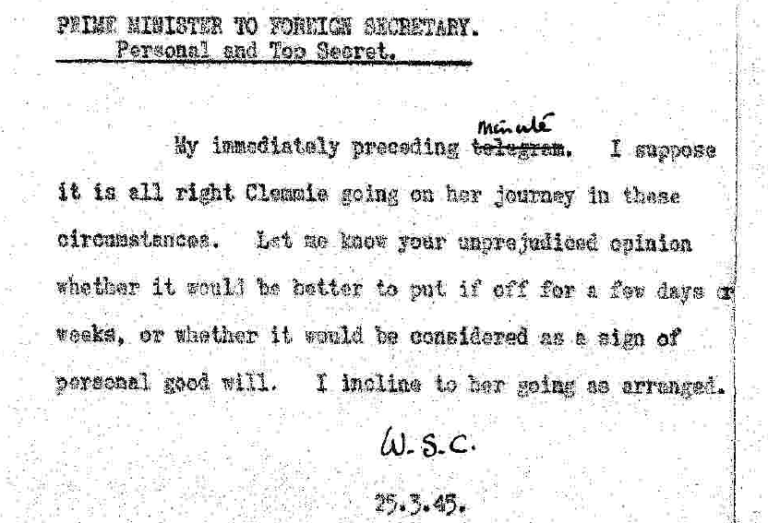

However, Winston was worried about the timing of the trip, for great tensions had now emerged in the Grand Alliance. Early in March 1945, Soviet intelligence services informed the Kremlin that British and US representatives had met German emissaries in Bern, Switzerland, to discuss a potential separate peace between Germany and the Western Allies, a proposal that violated the Tehran and Yalta agreements with the Soviet Union. The revelation caused discord and distrust between the three Allied leaders when Stalin raised the issue[ref]Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume 7: Road to Victory, 1941-1945 (London: Heinemann, 1986), p. 1255[/ref]. In a letter to Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, he indicated his approval for Clementine’s trip to go ahead, but asked rather anxiously for counsel on whether her arrival should be delayed (FO 954/26C/591):

Deciding that the trip should proceed as ‘a sign of personal good will’, Winston shook off his reservations and allowed Clementine to go. It proved to be an inspired decision.

From the moment of her arrival at Moscow airport on 2 April, she and her companions were overwhelmed with gifts, including a ‘huge bouquet of red and white roses’ from Polina Zhemchuzhina, the wife of the Soviet Foreign Minister Viacheslav Molotov, which had been ‘cut in Moscow hot houses only that morning’. These were followed by non-floral tributes so numerous that, as Clementine’s secretary, Grace Hamblin, wrote to her family, ‘at one time we wondered if the plane would carry them back to Britain’[ref]Knight, pp. 257-8[/ref].

Spending her first week in Moscow, Clementine would be received ‘most amiably’ on 3 April by Commissar Molotov; he ‘referred to present difficulties but said they would pass and Anglo-Soviet friendship remain’. She was later guest of honour at a ‘lovely banquet’ hosted by the Molotovs. On 7 April, Stalin welcomed Clementine to the Kremlin, and thanked her for all her fundraising efforts. There she presented the Soviet leader with a gold fountain pen, a personal gift from Winston, and told Stalin: ‘My husband wishes me to express the hope that you will write him many more friendly messages with it’. Stalin, smiling, accepted the gift, but apparently quipped: ‘I only write with a pencil’[ref]The Kremlin Letters, pp. 577-8[/ref].

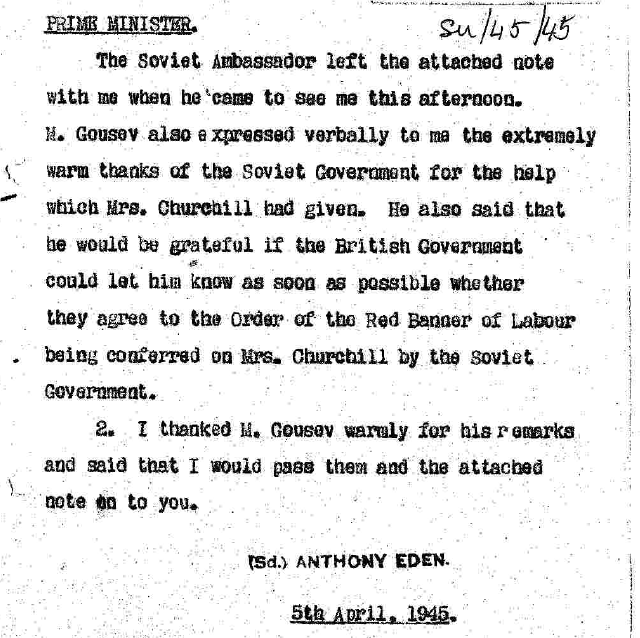

Later that same day, Stalin drafted a personal message to Churchill: ‘I had an agreeable conversation with Mrs Churchill who made a deep impression upon me. She gave me a present from you. Allow me to express my heartfelt thanks for this present’[ref]Ibid, p. 577[/ref]. By that time, Stalin had decided to bestow another gift upon the already ‘gift-laden’ delegation, a fact of which Winston was already aware. Two days earlier, the Soviet Ambassador to the Court of St James, Fedor Gusev, had called upon Eden at the Foreign Office to ask if the British government would agree to the conferring on Mrs Churchill of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour, an award given by the Soviet state for exceptional working achievements (FO 954/26C/600):

On 9 April, Clementine, Miss Johnson and Miss Hamblin departed Moscow on a special train in which they would tour the western and southern Soviet Union, visiting Leningrad first, followed by other war-ravaged areas, such as Stalingrad, Odessa, Kursk, the Caucasus and the Crimea. They travelled in grandly furnished train cars equipped for dining and accommodation, together with serving staff, guides, translators, a protective Red Army detachment and a troupe of musicians, singers, dancers and technicians who provided constant entertainments, including opera, ballet, theatre, cinema, and one evening of traditional song and dance every week[ref]Knight, p. 259[/ref].

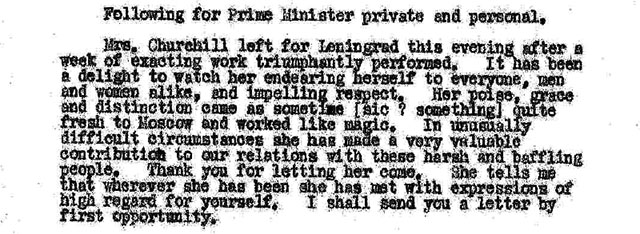

On the evening of their departure, Clark-Kerr sent an update for the Prime Minister to the Foreign Office, in which he conveyed his gratitude to Churchill for allowing her to come and spoke of the wondrous affect her presence was having on relations with the Soviets (FO 954/26C/625).

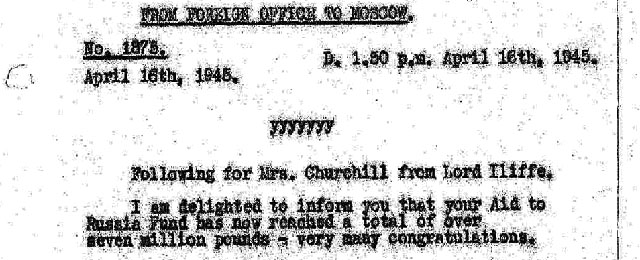

Throughout the tour, Clementine’s objective was to visit as many hospitals as possible in order to see how Aid to Russia Fund medical supplies and equipment sent by the British Red Cross were being utilised. She had the opportunity to see the Leningrad Orthopaedic Clinic for Children; there she was, rather movingly, photographed holding a two-year-old Russian infant in her arms, the child having just delivered a tiny bouquet of flowers on behalf of the hospital. She later wrote: ‘I have never been more deeply moved in my life than by the spectacle of child victims of the siege'[ref]My Visit to Russia, Frontispiece & caption & p. 28[/ref]. While she was touring, a telegram arrived on 16 April from Lord Iliffe, the chairman of the Duke of Gloucester’s Red Cross and St John Appeal, who was also a patron of the Fund. He delivered momentous news (FO 954/26C/638):

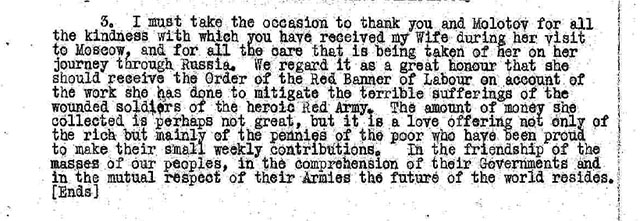

On 12 April, US President Franklin Roosevelt died suddenly at his private residence. Churchill communicated his own feelings of distress two days later in a telegram to Stalin, and underlined the importance of their continued friendship as remaining original partners of Grand Alliance. He thanked Stalin and Molotov for the warm reception of his wife in Moscow, and expressed gratitude at her award of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour. He suggested that the ‘love offering’ of Clementine’s fund would be a fundamental underpinning of future Anglo- Soviet relations (FO 954/26C/633).

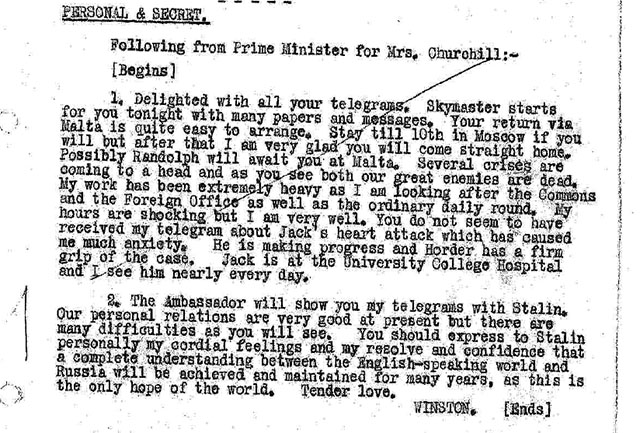

By the beginning of May 1945, Clementine returned to Moscow as her Soviet tour was now drawing to an end. Responding to continuous invitations to lengthen her visit, she elected to stay on for another week. In a private telegram, on 3 May, Winston reluctantly consented to her extending the tour. He was very depressed and clearly missed her greatly. He also informed her of the condition of his brother Jack, who was recovering in hospital from a heart attack, and confided his own personal fears about a decline in relations between Britain and the Soviet Union (FO 954/32D/880):

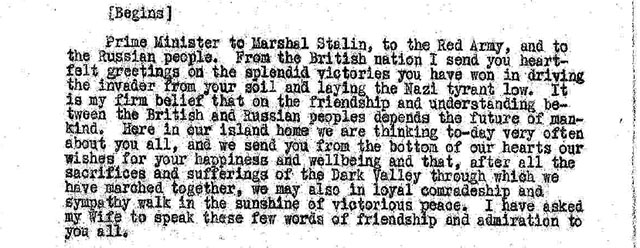

On 8 May 1945, at the close of a long day of national celebrations for VE Day, Winston sent a telegram to Clementine in which he communicated a specially drafted message of tribute to the Soviet people for her to read out on Radio Moscow, with the permission of the Kremlin. However, there is little evidence that Churchill’s hastily-drafted speech was approved by Stalin or that any broadcast occurred (FO 954/32D/909):

On the following day, 9 May 1945, the day that Stalin chose to mark the Soviet Union’s ‘Victory Day’, Clementine was honoured by the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, who held a luncheon in her honour. There she would be presented with a gift comprised of a specially-made folder, which contained a short biography and a series of mounted photographs of Soviet partisan, Zoia Kosmodemianskaia, one of the most revered of wartime heroines of Great Patriotic War, who was publicly hanged by the Nazi occupiers and posthumously awarded the ‘Hero of the Soviet Union’.

This controversial gift included photos graphically depicting her death and a moving account of this partisan-martyr’s life, written by her own mother. Indeed, some would question the appropriateness of such a gift, especially for the wife of a head of government. Claire Knight, who has studied Soviet gift-giving conventions during Clementine Churchill’s visit, observes that, as Britain had given the Soviet Union the ‘gift of life’, the Soviets had responded by giving Britain the ‘gift of death’[ref]Knight, p. 265-6[/ref].

Moreover, this parting gift was a reminder of the sacrifice of Soviet women in the war, something which was intended to resonate strongly with Clementine, not only as the wife of a powerful war leader, but as a serving woman who had led heroic national efforts to provide aid to a stricken Soviet population.

Clementine bade farewell to Moscow, and to Soviet Russia, on 11 May. As her plane took off from Moscow airport and soared into the sky, Clementine would later write, ‘I prayed, as I turned to take my farewell look at Moscow, “May difficulties and misunderstandings pass, may Friendship remain”’[ref]My Visit to Russia, p. 58[/ref].

Please note: Due to the Coronavirus measures currently in place, The National Archives is closed to the public until further notice. This blog was researched online using digitised Foreign Office records combined with secondary sources. You can search our digitised Foreign Office records documenting Britain’s wartime relations with the Soviet Union, using our Discovery catalogue.

This is one of the unsung but superb service which you give for making all this material available.

Very interesting! I admit I do not know about the visit.

That is a fascinating article, I had never heard about it before.

Brilliant. This shows the humanity of Churchill and gives a further insight into his complex personality. In my childhood the memory of Churchill’s attitude during the General Strike was still raw (the males in both sides of my amily were Dockers in the east end of London.) This memory of his attitude to ‘the working class’ no doubt contributed to election of the Attlee Government in the first post-war Gemeral Election.

Dan Regan MBE OStJ PhD. Date of Birth 2/8/1932.

I WAS 9 YEARS IN 1945 – I REMEMBER MY FATHER SAYING HOW MR CHURCHILL HAD HELPED THE RUSSIANS & I REMEMBER SEEING MANY THINGS BEING SENT TO RUSSIA FROM HULL & MY UNCLE ALBERT BEING ON THE CONVOYS [HE WAS PROUD OF HIS MEDAL FROM RUSSIA -WHICH HE GOT BEFORE HIS BRITISH MEDAL

IT WAS A REMARKABLE STORY ABOUT MRS CHURCHILL GOING TO RUSSIA I WAS NOT AWARE OF THE DETAILS [ THANK YOU FOR THAT INFORMATION]

THE PUBLIC ARE NOT AWARE THE GREAT HELP THE RUSSIANS WERE TO THIS COUNTRY IN WW2

Such fascinating information about all the “behind the scenes” stuff. Churchill’s later defining of the schism that was brought by the “iron Curtain” must have been a terrible disappointment to him – akin perhaps to a personal failure of all his efforts and diplomacy in trying to maintain the wartime relationship into a new world order..

“… especially for the wife of a head of state.” ref. Mrs Churchill in Moscow

of “Government”, of course

Thanks for spotting – now corrected!

Mrs Churchill was many things but she was not the “wife of the head of state” (3rd paragraph from end).

She was the wife of the head of government.

ITS GOOD TO HEAR OF UK AND RUSSIA FRIENDSHIP .

DURING THE WAR OF 1939-1945

I WISH IT TO CONTINUE

R HAYWARD

My grandfather Maj General JET Younger CB , KStJ, accompanied Clemmie Churchill on this visit to Moscow, in his capacity as Secretary of the Joint War offices of St John and the Red Cross.

On the day when war in Europe was announced by Churchill to be over, my grandfather happened to be crossing Red Square dressed in his full military uniform, on his way to an important engagement. The Muscovites there were in extremely high spirits as one can imagine. Spotting a British general crossing the Square and charged with highly enthusiastic emotions, they surrounded him and tossed him high in the air much to his mortification. He was very concerned that his smartly polished shoes would be damaged !

His objective was to reach safety which he managed to achieve with the cooperation of an astute door guard who recognised his predicament, letting him in to avert further jeopardy to his smart attire. With the guards assistance, they called the British Embassy who promptly dispatched a vehicle to the rear of the building to collect him to regain his purpose of the day.

In his diary, he wrote that there couldn’t be many British generals who had suffered such an experience in uniform in Red Square.