New Year Openings at The National Archives are a time for looking back at the world of 30 years ago, marvelling at how much has changed, or, as a recent blog post on Renewing the Values of Society demonstrated, how much has stayed the same.

What government was doing about the web in 1982 hasn’t received the publicity of the Falklands files. Mainly because, you might think, in 1982 the World Wide Web was little more than a gleam in the eye of Sir Tim Berners-Lee, called ENQUIRE. But while war was raging in the Falklands, a group of civil servants from the government’s Central Computing and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA) were trying to second guess the future (BN 120/8 and BN 120/9).

Pre-web, there was plenty of computing going on in government departments; most of it hidden away on the one large machine each department had, with a scattering of terminals that connected staff in distant offices to the machine. The CCTA were trying to establish how much need, if any, there would be to transfer data from one government department’s machine to another. Another 1982 anniversary was the official adoption of the TCP/IP protocol, building block of the internet, by the US Department of Defense. In 1982, data was being exchanged across the world, but the internet was still very much part of its US Cold War communications origins. In the UK civil servants were speaking not of nets, let alone internets, but packet switching. The climate for building networks was not very encouraging. There was a waiting list for new telephone lines – which it was hoped the privatisation of British Telecom would address – meanwhile the first Data Protection Act (1984) was stirring in Parliament; there was an awareness of the public’s reluctance to have their personal information shared across departments by these worrying computers that sent you gas bills for £1,000,000,000.99p. And cost was a major factor: to save taxpayers money data from local benefits offices was sent by the cheaper overnight tariff to the DHSS central computer in Newcastle.

But not only were the circumstances unpropitious for transmitting information, the CCTA files also demonstrate the difficulty of thinking about the future when you only have the vocabulary of the present: sending data in the sense of the repetitive number crunching done by the computer over a telephone line was refereed to as ‘non-voice communication’. Looking forwards to the next ten years the CCTA surmised that there might be a dramatic increase in the number of data terminals (linked to the one departmental machine), perhaps in the order of 30,000 to 40,000, although some disagreed that ‘non-voice communication’ would increase so rapidly.

At home, in schools and in small businesses, people were staring to use ‘microcomputers’ (the BBC Acorn BBC Micro was launched at the end of 1981 and the Sinclair ZX Spectrum in 1982), teaching themselves basic programming languages such as, er, BASIC. IT, whether at home or in the office, was flat, monochrome (generally green), text based, and static. You never seemed to be allowed to use more than eight characters to name anything. ‘Images’ had to be created by manipulating keyboard characters; creativity was all about overcoming the constraints of what you couldn’t do.

When the web, with all its liberating creativity and connectivity, came a decade or so later governments were early adopters of it. At first the archival world didn’t quite know what to make of it; archives dealt with records, so there was a lot of debate about whether or not websites were records, there was a feeling that even if they were records, the stuff that archives wanted was the real solid stuff going into files in offices, the stuff of New Year Openings, not the ephemeral and open postings on websites. But as the web grew, it became apparent that whatever you wanted to call the material on websites, much of it only existed there, and was prone to disappearing pretty quickly; The National Archives has been systematically archiving the UK government web domain since 2003, with many instances going back to the mid-90s.

Ministers and civil servants started blogging, and then tweeting, and people started answering back. In the UK Government Web Archive, we’ve taken up the technical challenge to capture all this (even Twitter – watch this space), to record the new ways that government is interacting with its citizens. But none of it is secret. In 2033, people might look in the UK Government Web Archive and think, Twitter, how quaint! (or even, ‘websites, how quaint!), but they won’t be seeing anything they couldn’t previously have looked at. There won’t be that frisson we get at New Year Openings when the answers to that great historical question, ‘What was really going on?’ come tumbling out.

However.

Imagine when you look at material from the web archive, you didn’t see this:

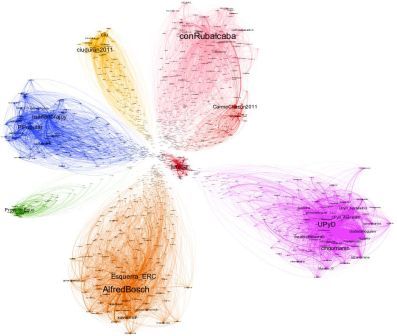

But something like this:

From: Tweeting the campaign: Evaluation of the Strategies performed by Spanish Political Parties on Twitter for the 2011 National Elections[ref] 1. Pablo Aragón, Karolin Kappler, Andreas Kaltenbrunner, Jessica G. Neff, David Laniado, and Yana Volkovich, Barcelona Media Foundation, Barcelona, Spain [/ref]

Researchers in Spain have used Twitter data to create this social graph of retweets from the 2011 Spanish election campaign. Analyses and visualisations such as this one demonstrated that electioneering tweeting went on almost exclusively within the party circles of its supporters; Twitter was not a means to engage with the opposing sides.

This is information you can’t get from looking at one, or even lots of web pages.

There is endless scope for using the whole UKGWA collection as one set of Big Data. In some ways websites, with their mix of text, images, videos, seem the opposite of a dataset, but across the UK Government web domain there are a vast number of instances of the same kind of structured data: as well as Twitter feeds there are links to be analysed (see the work being done by Scott Hale at the Oxford Internet Institute); location information – addresses, postcodes; job vacancies, even images: ‘Who is shaking the Minister’s hand?’ may sound like a trivial question, but who knows what conclusions might be drawn from an image analysis of the thousands of photographs of such interactions we have (thanks to my colleague Claire Newing for suggesting this one).

Like the civil servants of 1982, we don’t know what new technologies the future will bring, but already there is a growing community of tech savvy researchers, adept at data mashups and visualisations geared up to explore an uncharted world of hidden secrets in the UK Government Web Archive – and you won’t have to wait 30 years for the answers.

The issue of data protection did not first arise in 1984 but goes back to the use of computers for the 1971 census of population and the public’s mistrust over the possible mis-use of the data just like it had been in 1911 despite the Government assurances in 1911 it wouldn’t be but was. The result is that the 2011 census will be almost totally unusable for family history purposes in 2112. Around 1971 the Government set up committees on the issue of privacy and computers and you can see that putting everything on a computer in Newcastle (wasn’t that the one that lost the 2 cds listing all child benefit claimants?) was just a cost-cutting exercise.

It is not actually true that was has been captured by the web pages projects were open web pages as they clearly were not on the Internet, as governments do not put out information on projects that had yet to start.

David,

Thank you for sharing your views with us.

Linda