Jordan Megyery working in Collection Care

I am currently an intern on the one-year Icon Photographic Conservation programme, working at both The National Archives and the Tate. I’ve been based at the Collection Care department at The National Archives for six months, under the supervision of photograph conservator, Jacqueline Moon. A significant part of my time here has involved working with the film collection, which includes X-rays, microfilm and still photo film, often found within paper files and records.

Surveying and understanding our film collection

Until recently, little was known about the film collection held at Kew. However, with the help of a team of hard-working volunteers, we have embarked upon a widespread survey to give us a greater understanding of the range of film items held in the collection, documenting where they can be found and, most importantly, the condition that they are in.

Our volunteers working hard on the film survey in Collection Care

Deterioration of film

Monitoring the condition of our film collection is important because certain film types can deteriorate at an alarming rate. Cellulose nitrate, the earliest type of plastic used in the manufacture of film, becomes sticky as it deteriorates; it adheres itself to surrounding documents and the image is eventually destroyed. Cellulose nitrate was replaced by cellulose acetate in the 1950s, but it too was soon found to be equally unstable, becoming acidic, distorted and increasingly brittle as it ages.

Some of the most deteriorated film highlighted by the survey is held within the PIN 26 files: Disability Pensions Award files from men and women injured in service during the First World War. These are fascinating documents and contain X-rays on both cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate film, many of which have unfortunately become severely degraded and unusable in their current state.

Cellulose nitrate X-rays which have become sticky and adhered to each other and to a polyester sleeve. The X-ray image has now been destroyed

Cellulose acetate X-ray with severe channeling caused by shrinkage of the cellulose acetate base

Saving degraded film

The discovery of the degraded film made us question whether there was anything that could be done to save these objects. For film made from cellulose nitrate it might already be too late, as the image is destroyed as the film degrades. In the case of film objects made from cellulose acetate, however, even though they might be brittle or cracked and the image masked by the distorted cellulose acetate layer, the image information is still there and can still be saved.

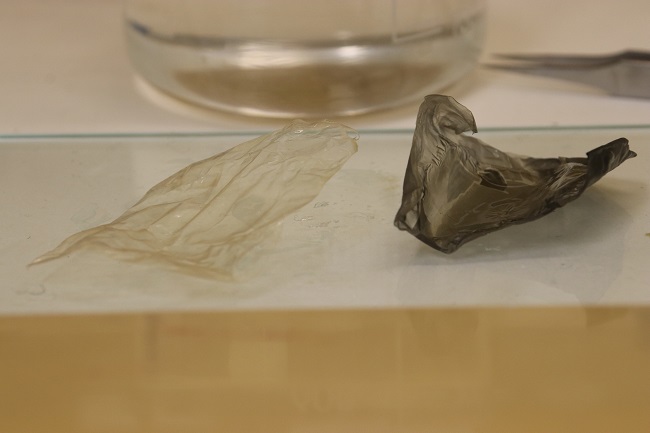

I’ve been testing ways of separating the image layer from cellulose acetate film to see if this could be a viable option for preserving these objects. Separation, which I have been testing on non-collection items, involves immersing the film in a series of solvent baths to release the cellulose acetate base from the thin layer of gelatin which holds the image.

Results have been promising and the treatment has the potential to save countless objects which would otherwise be lost, but the treatment is not without its risks. Consequently, additional testing is needed before the procedure can be carried out on film items from The National Archives’ collection.

Separating the cellulose acetate film base from one of the test samples

What we are doing in the meantime

Until a method of saving degraded film is optimised, the most effective thing we can do to preserve our collection is to ensure that it is stored in carefully controlled conditions. For this reason the Collection Care department has invested recently in a fridge that was manufactured originally for the confectionery industry.

With this new piece of equipment we will be able to store vulnerable film items at cool temperatures and low humidity levels, slowing deterioration and preserving the film collection for as long as possible.