In May 1921 W E B Du Bois wrote to Winston Churchill, then Secretary for the Colonies, requesting help and encouragement with the London part of the Pan-African Congress. Du Bois wrote:

‘I am writing to ask if we could arrange in some way to receive from your office some help and encouragement. I should like best to have a representative of the British Colonial Offices to speak to our Congress and to state in some general terms the main ideas of Great Britain toward her Negro subjects, civilised and uncivilised. If this would not be feasible perhaps you might suggest some other way in which you would be willing to help.’

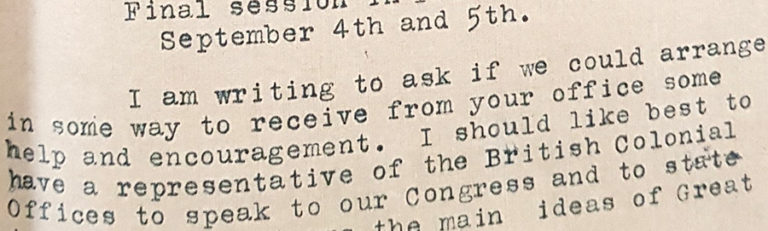

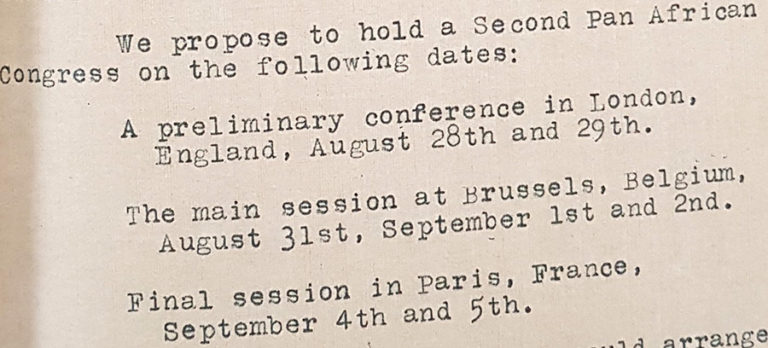

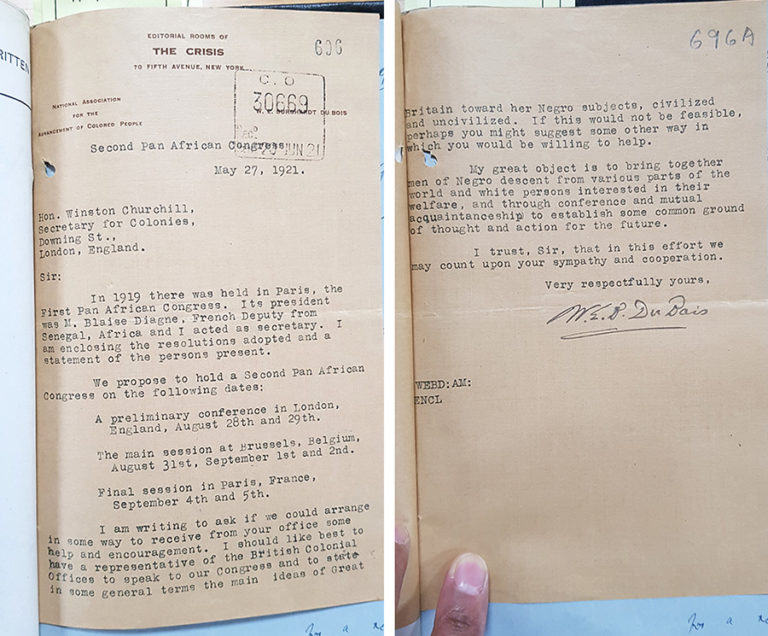

It is a short letter, about one and a half pages long. This letter is typed on special brown headed paper of ‘The Crisis’ newspaper, which Du Bois edited. It is business-like, opening with a mention of the first Pan-African Congress in Paris in 1919 and stating that resolutions adopted from that Congress are enclosed. It then sets out the intention to hold three parts to the second Pan-African Congress in 1921, starting in London on 28 and 29 August. Then moving to Brussels for the second leg on August 31 and September 1 and 2. A final part would take place in Paris on 4 and 5 September.

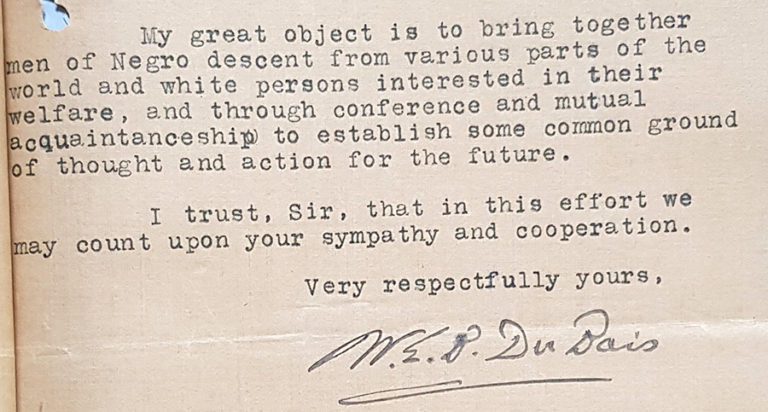

Du Bois ends the letter in a conciliatory tone hoping that the Congress will foster greater awareness and common ground between black and white people. It is this same tone that informs the outcome of the Congress itself. Du Bois signs off his letter to Mr Churchill with the following line: ‘I trust, Sir, that in this effort we may count upon your sympathy and cooperation’.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, often referred to as W E B Du Bois, is known for his writing. He wrote in various genres including poetry, novels, journalism, scholarly monographs and autobiographies. He was the first African American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, in 1895. Some of his works have become celebrated texts, often reflecting philosophically on the black experience in the US.

At the end of the First World War, Du Bois was exercised by the opportunity to lobby the most powerful imperial powers. He went to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 for this purpose and it was here that he helped set up the first Pan-African Congress. He recognized that European powers like Britain, France and Belgium needed to be lobbied so as to get a better deal for people of colour. Situating the congresses in the three capitals was a natural next step. His letter is to the then Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, and highlights the importance that men like Du Bois placed on Britain and its empire, and therefore we have a copy of the letter (CO 323/878).

London was the beating heart of the British empire. It was the seat of the British government. His letter indicates that he was keen to engage Britain with the congress and to get them to take his initiative seriously. London was also a hub where others who linked into the black and anti-colonial struggle could easily attend.

Despite the evident enthusiasm with which he wrote to Churchill, the Colonial Office officials charged with responding to the request, struck an altogether less enthusiastic tone, saying privately it was best to decline the invitation to send a speaker by saying they were currently too busy. There was also uncertainty expressed at what kinds of resolutions may be passed in London, or which representatives will be present.

However, the Colonial Office was satisfied that the resolutions drafted at Paris were not too extreme. The comments from officials indicate that at this stage the Congress was not something to be taken too seriously, and the reply that was drafted by Gilbert Grindle said that, with regret, it would not be possible to arrange for a Colonial Office representative to attend.

Further correspondence in The National Archives collection from August 1921 includes a note from the British Embassy in the US sending information relating to Du Bois, including a copy of The Crisis newspaper from July 1921 which promoted the London Congress. It’s interesting to note that the Colonial Office continued to be fed updates in relation to the London Congress, suggesting that there remained an interest in the Congress even if no one from the Colonial Office had the time to attend.

While the British government declined the request to send an official, the Congress in London was able to gather interest, including from figures of black African heritage in Britain at the time.

The first day of the Congress was 27 August 1921 in the Central Hall in London. A description of the delegates indicates that people from diverse backgrounds attended. In attendance at the Congress were black British representatives including the former Mayor of Battersea and the first black person to hold this office, John Archer. Archer led the second day’s proceedings with Du Bois. The first day was co-led by the British-based Dr Alcindor, who along with John Archer was involved in the African Progress Union, an organization founded in London, which campaigned for black people’s rights across the world. Also in attendance, and reflecting the diversity of the Congress, was the future Indian communist MP for Battersea, Shapurji Saklatvala. In addition to those from Britain, the London Pan-African Congress had representatives from South Africa, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Lagos, Grenada, the USA, Martinque, Liberia, British Guiana, Jamaica and people of African heritage living in London. The outcome of the Congress in London was far less militant in tone than may have been expected. It appealed for greater fairness, inclusion, education and self-development.

Du Bois’s writings are what many consider heroic, in particular his powerful ability to reflect on and express the experience of black and colonized people, and their struggle to prove their humanity and gain better rights and ultimately freedom and equality.

Du Bois was also of his time, born and raised in the Victorian era. At the time of the second Pan-African Congress, his language and views on race and gender for example, would from today’s vantage point appear strange at times. But the sentiment in his writing and his activism ultimately reflect a deep humanity which is admirable.

As we celebrate Black History Month 2020, Du Bois is a fitting figure to be included as part of the month. Having this letter from Du Bois in The National Archives’ collection sheds further light on this towering figure. We get a glimpse of another side of Du Bois, the activist and organizer. Having this letter in our collection is both unusual and special.

On the Record: series four available now

In our latest three-part podcast series we’re exploring stories in our collection with the theme of heroic deeds. In the episodes you’ll hear about spies parachuting into enemy territories and knights slaying dragons. You’ll also hear about health inspectors trying to improve the living conditions of poor Londoners, and leaders using their skills to organise for change.

In the forthcoming episode on heroic deeds, available on 29 October 2020, we explore the story of W E B Du Bois further.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which we have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have marked the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain and Refugee Week by delving into lesser-known personal stories from our collection.