D-Day, 6 June 1944, the turning point of the Second World War, was a victory of arms, a heroic feat of military strategy and raw courage. But it was also a triumph for a different kind of skill: it was an astonishing feat of paperwork.

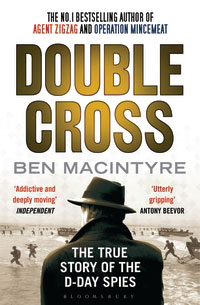

Double Cross

Operation Fortitude, which protected and enabled the invasion, and the Double Cross system, which specialized in turning German spies into double agents, deceived the Nazis into believing that the Allies would attack at Calais and Norway rather than Normandy. It was the most sophisticated and successful deception operation ever carried out, ensuring that Hitler kept an entire army awaiting a fake invasion, saving thousands of lives, and securing an Allied victory at the most critical juncture in the war.

The Double Cross system depended on a filing and archive system that was vast, complex and meticulous. It is not too much to say that without the extraordinary record-keeping system devised by the spy-runners, the great D-Day deception might have failed, and the history of the 20th century would have been very different.

The great British talent for keeping and maintaining records played a vital, but largely unacknowledged role in winning the Second World War. Most of the wartime files relating to the Double Cross deception, once top secret, have now been released to The National Archives. That material has formed the evidential basis for my last three books: Agent Zigzag, Operation Mincemeat and Double Cross. Each of these books tells a story extracted from the wartime files. Indeed, without this huge trove of documents, these books could not have been written.

It was only when I began to dig into the archives that I realised the staggering amount of paperwork generated by wartime espionage, the running of agents and double agents. John Masterman, chairman of the Twenty Committee (so called because 20 in Roman numerals, XX, forms a double cross) observed: ‘only a well-kept record can save the agent from blunders which may blow him, or inconsistencies which may create suspicion’. The agent files of MI5 grew to a ‘truly formidable size’, each one indexed and cross-referenced. Each case officer had his or her own secretary just to keep track. Masterman again: ‘The messages of any one agent had to be consistent with the messages sent by him at an earlier date and not inconsistent with the messages of other agents.’ They also had to keep track of the enemy. By the middle of the war MI5 had compiled a virtual Who’s Who of German spying, running to 20 volumes. The case of the double agent ‘Garbo’ alone generated some 21 files, more than a million pieces of paper

Ben Macintyre

For a writer, such rich source material is a joy. The experience of spending so many months in the archives not only allowed me to immerse myself in the wartime world of espionage, but left me with renewed respect for the very British talent for record keeping and preservation. The Germans, with all their reputation for efficiency, had nothing to match it. The great D-Day battle was won on the beaches of Normandy, but also on paper, in files that were carefully maintained, and then preserved for all time. The release of these files to The National Archives represents an extraordinary sea-change in attitudes towards official secrecy. Until a few years ago these organisations did not, officially, exist.

These were documents written by people who never expected them to be made public. This gives them a very particular quality. They are honest in a way that many official government records are not – most officials, knowing their work will one day be scrutinised outside, seek to frame the record in some way, and even to distort it. The spies and spy-masters in these stories do not. When it goes wrong, they make no attempt to cover it up. To read these documents is to eavesdrop on a secret world.

The National Archives is the guardian of this crucially important heritage that is only now, more than 70 years later, coming to light.

As a final testament to British record-keeping, I will quote the words of another spy. In 1977, Kim Philby gave a lecture to the KGB, in which he advised Russian spies to try to penetrate MI5, first and foremost, because of what he called its ‘immeasurably superior filing system.’ Philby knew that paper is power. From the greatest spy of all time, that is a sort of backhanded compliment to great British archival tradition.

We fought them on the beaches, we fought them on the landing grounds, in the fields and in the streets. But we also fought them among the filing cabinets, and won.

————————————————————————————————————————-

This blog is part of the Writer of the Month series. In this series well-known authors share their own experiences of using archives for their writing and explore how aspiring authors could also use archives themselves. Blog posts written by guest authors are the authors’ opinion alone and do not necessarily represent the views of The National Archives.