Last week a team from The National Archives took part in a Watergate anniversary event at the Houses of Parliament, organised by the All Party Parliamentary Groups for Archives and History, and for British-American relations. A panel discussion between Iwan Morgan, Emeritus Professor at University College London, Chris Evans MP, Tim Stanley of the Daily Telegraph and the journalist Bridget Kendall explored the context and legacy of the Watergate scandal.

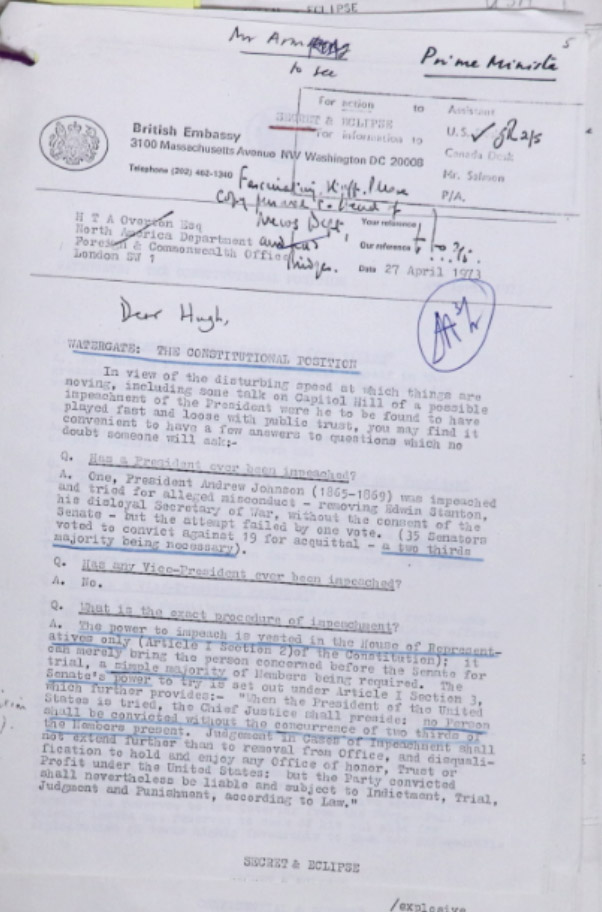

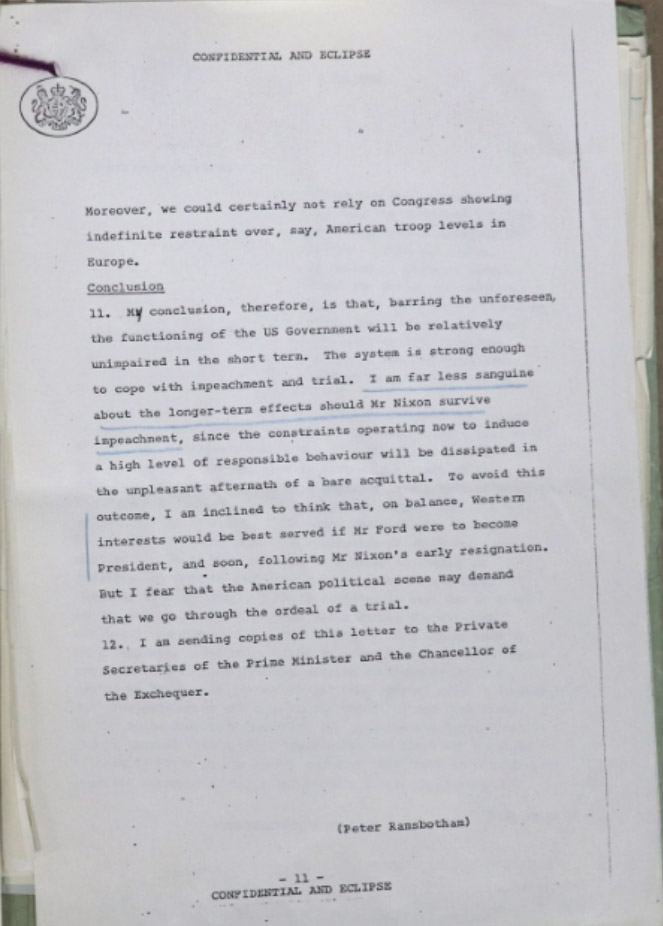

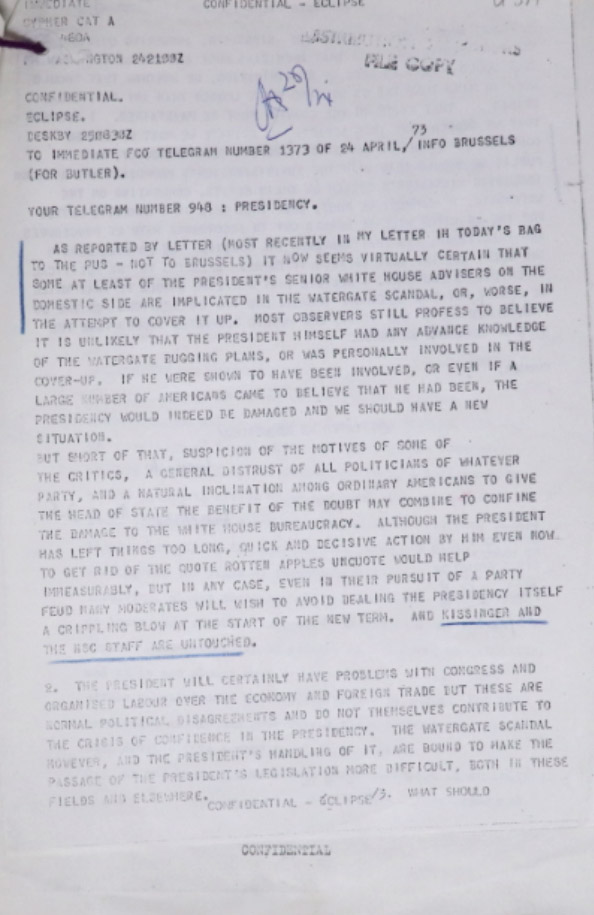

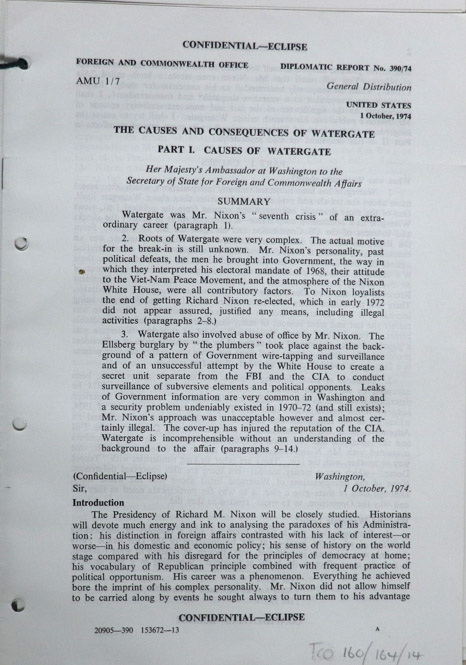

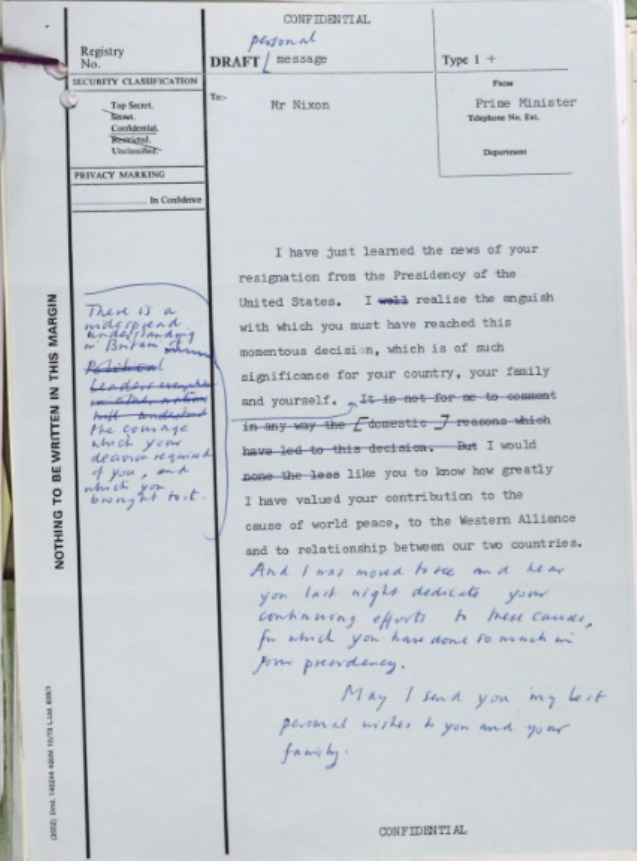

We provided a display of letters, reports and telegrams from the archives. These documents offer the British perspective on the series of events as they unfolded, from the initial break-in at the Watergate Hotel, through the televised hearings, the revelation of the taped White House conversations, to the moment when President Richard Nixon resigned two years later to avoid impeachment.

The documents we presented included despatches from the British ambassadors in Washington, and correspondence from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Prime Minister’s office, many with hand-annotations as they circulated between different readers. The length of some of the reports and analyses from the British embassy in the US is indicative of how difficult it was for the British government to respond to such an unprecedented situation. What would it mean to impeach a President? How would it happen and what could possibly result? It was new ground, legally and constitutionally, and the documents reflect the British government’s efforts to take a diplomatic position as new evidence emerged. Since 1974, there have been three impeachments of US presidents, so Watergate no longer seems quite as exceptional as it did to the authors of the archival documents. However, 50 years on, these documents remain fascinating reading.

For many in government in the UK, Nixon was a valuable ally to British interests. The British ambassador in Washington wrote to Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, that ‘Nixon’s understanding of the complexity of the international system is of quite unusual degree in this continent … and of extraordinary benefit to us and to Europe as a whole. Its loss would be grievous’ (6 July 1973, PREM 15/1992). In 1973 the British government was fairly confident that Nixon would weather the storm of the accusations. However, the ambassador advised that any support for Nixon from the British government should be offered cautiously and discretely. It was still assumed that Nixon wouldn’t have been party to (or be implicated in) what was described as ‘electoral skulduggery’ by a ‘group of amateur desperados’ (6 July 1973, PREM 15/1992). When it became clear that Nixon was, in fact, involved, the archival documents record relief that Henry Kissinger (another perceived ally of the British on the US political stage) was untouched by the scandal.

We also see the British struggling to come to terms with the implications of the unfolding legal drama for the nature and stability of government in the US. In 1974 the British ambassador reflects that:

‘In Watergate a whole series of trends in American politics come together. On the surface many of the actions of the protagonists seem hard to explain. But set against the background of the civil disorders of the ‘sixties, the Viet-Nam War, the determination of a Conservative Administration to quell those excesses, the particular traits of Mr Nixon’s personality and the concentration of power in the White House, much becomes comprehensible.’

The final outcome – Nixon’s resignation – was seen as a relief, not for reasons of moral righteousness but as an end to an era of political uncertainty that was seen as damaging not only for the US but for British interests and those of ‘the entire Western World’ (Despatch from 1 October 1974, FCO 160/164/14).

The discussion in our archives about Watergate also offers insight into how political and diplomatic exchange was being altered in the era of new communications and media technologies. So much was known and so quickly distributed by the global news media, that the role of UK political agents in reporting current affairs was being partly superseded. The British ambassador writes to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs: ‘I have not so far attempted to report formally on what has become known as the Watergate Affair, not least because it has been so extensively covered by press and television around the world’ (6 July 1973, PREM 15/1992).

The ways in which the media, and social media, allow us to follow political action in real time is taken for granted today. In 50 years our perspective on these events has already changed radically. It will be interesting to see how that perspective might change again if we revisit these archival records in another 50 years from now.

The reference DR 390/74 is actually FCO 160/164/14, the DR reference is not a TNA reference. The Foreign Office did not exist by that name in 1973 it had changed to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 1968.

Thank you for noticing those slips in the captions David, they have now been corrected.