One of the repercussions of world events at present is the shortage of grain exports from Ukraine, which is contributing to the general increase in the cost of living in the UK and across Europe. Looking back 200 years, there was a similar shortage of grain in Britain, partially caused by a war, which eventually forced the Home Office to take action. But was its plan of any use?

After 1750 Britain gradually became a net importer of grain, particularly from 1789. A series of poor harvests combined with an increasing population led to gradual increases in food prices. Britain was also at war with France, which made imports difficult, and by 1792 exporting grain was banned.

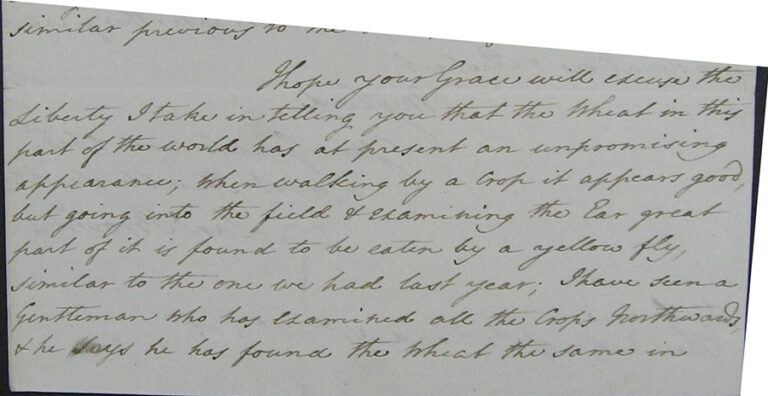

Letters received by the Home Office in 1795 show that there were other factors affecting crop production, including reports of disease in the wheat crop in Yorkshire. Wheat was being eaten by a yellow fly in Huntingdonshire, and farmers in Sussex had apparently held back their wheat to enhance the price, and had then been selling it secretly. In Middlesex the Clerk of the Peace wrote that in the Parish of Great Ealing arable land was disappearing, a third of it had been converted into pleasure grounds and nurseries, and less wheat had been sown due to the higher value of horse feed. In Scotland there were reports of speculative agents buying up grain before it was even brought to market, and in County Mayo, Ireland, the repressive measures of the military included the destruction of crops and the torching of dwellings.

The situation became so bad that, in 1795, there were riots and disturbances across the country. Letters received by the Home Office (HO 42/34) include reports of rioting in Coventry, and the Mayor of Portsmouth reports riotous behaviour abetted by junior ranks of the Gloucester Regiment of Militia. In August 1795, several canal construction workers, demanding affordable food, were arrested in Cambridgeshire, whereupon they threatened to muster 1,000 comrades to set all the prisoners free.

On 20 July 1795, the Home Secretary, The Duke of Portland, issued a circular addressed to the Lord Lieutenant of each county urging a more frugal use of bread in workhouses, hospitals and public charities, using a third less bread and substituting other foods instead.

But these suggestions were not good enough – government needed to know the size of the problem. So on 28 October 1795 a further circular was issued asking the Lord Lieutenant of each county to call a meeting of Magistrates and High Constables to gather information on the state of crop production in their county. He asked them to:

procure an account of the produce of the several articles of grain … comparing the same with the produce of a fair crop of every such article of grain in common years, and with the produce of the crop of 1794 of every such article of grain … and to report such account as early as possible.

Unfortunately the request was so vague that it revealed more about Portland’s own lack of experience in gathering statistics than it would yield in hard facts on grain. There were no measurements mentioned, quantities or units; he did not specify boundaries or areas to be measured; there was no timescale; and it took no account of farming procedures, techniques or costs. Portland underestimated the massive scale of the undertaking, and took no account of the unavoidable tendency for human beings to bend the truth for their own interests. It soon became obvious that the Home Office was ill-equipped to cope with the replies.

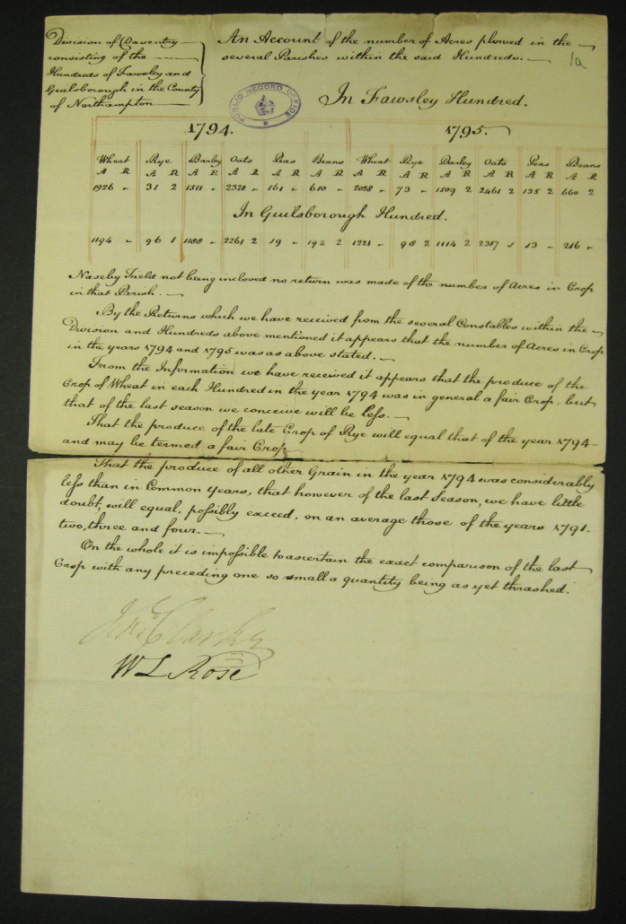

Within days the results started to come in, the first one being from the Magistrates of Daventry, Northamptonshire, who gave a cautious estimate of the number of acres in which wheat, rye, barley, oats, peas and beans were grown in 1794 and 1795. They finished by stating that ‘On the whole it is impossible to ascertain the exact comparison of the last crop with any preceding one, so small a quantity being as yet thrashed’.

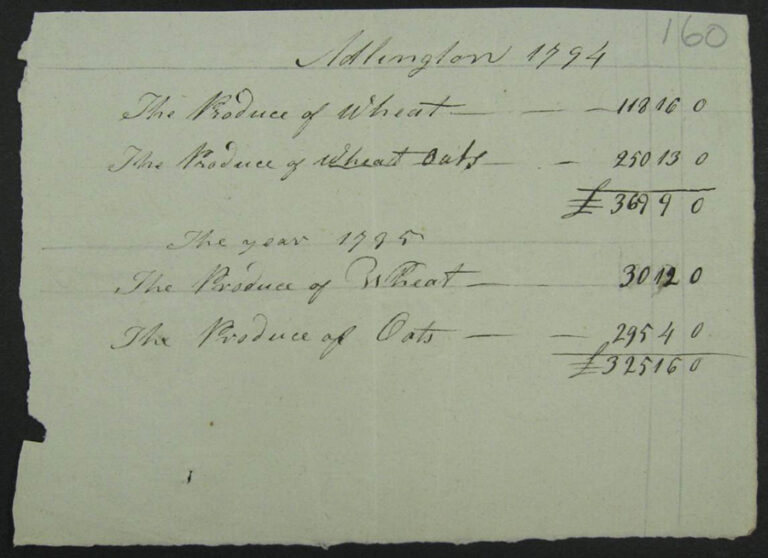

The return for Adlington, Lancashire, was a tiny slip of paper showing only the value of wheat and oats for 1794 and 1795.

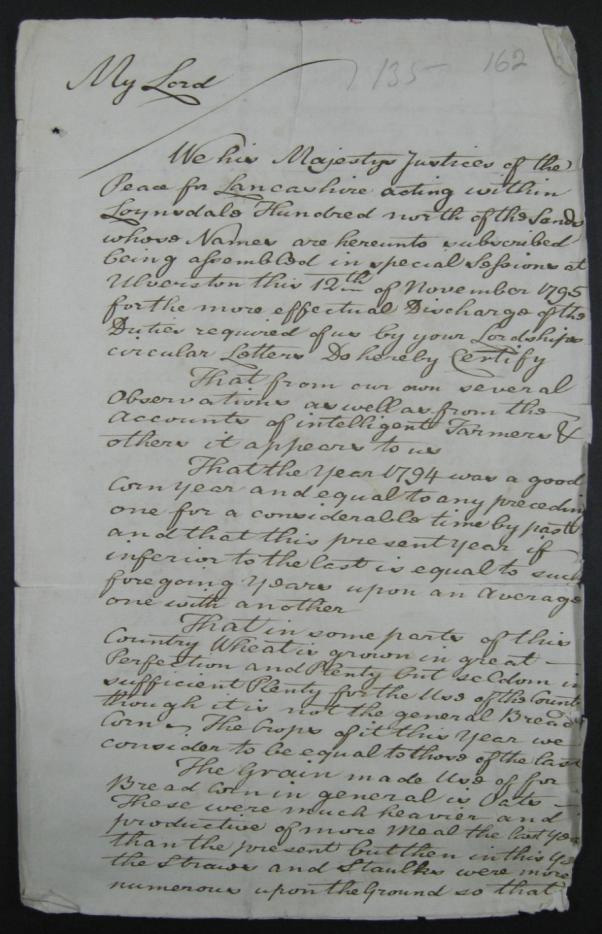

A third one was in the form a chatty letter from Henry Richmond Gale JP who had consulted ‘intelligent’ farmers who had revealed that 1794 was a good year, equal to any other for some time past. The present year, if inferior at all, was on a par with earlier years if taken as an average. Wheat had been acceptable, but they used oats for bread in that area, and last year they had been heavier and more productive, but this year there were more stalks and straws on the ground, so that ‘probably there may be not much difference’. Rye was only used for tanning leather, and beans were grown in the fruitful parts of the county, in very large quantities not only for horse feed, but for exporting to other parts of the country.

The returns show no consistency in terms of acreage, tonnage, value or cost.

Many exhibit a yearning to please Portland, due to the prevailing culture of deference, and despite a lack of actual facts on crops, the Magistrates are keen to make a return, however useless it is.

However, there were some who were not afraid to point out the failings of the scheme. The Earl of Radnor, Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire, wrote that he was at a loss to see how the magistrates of the county would be able to gather the information required to compile the crop return. The work would be ‘little more than guesswork and the assessment of the actual 1795 crop would require authority beyond that possessed by the magistrates’. Radnor requests further guidance from the Home Secretary on how to procure authentic information.

Some areas did not respond at all, and others were creating so much data it was incalculable. The Earl of Warwick wrote on Christmas Eve 1795, apologising for the delay, but stating that the reports were ‘so numerous as to make it impossible to make any reasonable conclusion unless they are calculated, – so I have set my steward to work on the task for ten hours per day’.

The Magistrates of Nottingham replied that reports had been received from most parishes, but they lacked accuracy, while almost every parish in Newark had refused or neglected to make a return, and those from Retford were accurate but undermined by the failure of many parishes to make a return at all.

The net result was that it was impossible to do any true calculations. Some returns were from a single parish, farm, hundred or county, while others were a combination of several. Many were incomplete, or under-estimated on purpose, or even guesses. Portland had nothing to compare the results to since it was the first time figures were required, and he could not use farmers’ profits to compare since prices were increasing through inflation anyway. It was in the interests of farmers not to complain at the high price of grain, and to keep it scarce, or at least to let it appear scarce. One report confirms that ‘Farmers are not threshing wheat as fast as in previous years hoping to get a better price in the spring’.

The Government soon realised that these reports would not give them any useful information, and so emergency measures were put in place:

- The exportation of corn was banned.

- The manufacture of hand and hair power was banned (which had been using 14% of wheat grown).

- Use of malt in distilleries was banned.

- The importation of grain was encouraged.

These measures did seem to help as prices started to fall temporarily during 1796 and 1797.

Although in itself a relatively fruitless exercise, the Crop Returns can be seen as a practise run at the gathering of big data, a practise also utilised in preparation for a new threat to the country in 1797/8 – a possible French invasion. The Government started gathering information on the numbers of cows, sheep, and horses, as well as crops, particularly in the south of England in preparation for moving these resources further in land should the French invade. In fact the French did land 1,400 men at Fishguard in Wales in a limited invasion in February 1797, but it was soon repelled.

The Home Office correspondence in HO 42 includes examples of various plans to cope with an invasion, including a 12-page essay by Charles Grey of Barham Court, Kent, entitled ‘A plan for driving the livestock of such parts of the country as may become exposed to the inroads of the enemy, in case of an invasion’. He outlines the raising of local yeomanry, the removal of cattle from potential landing sites and plans for the herding of 240,000 sheep to specific depots, to keep them out of reach of the French.

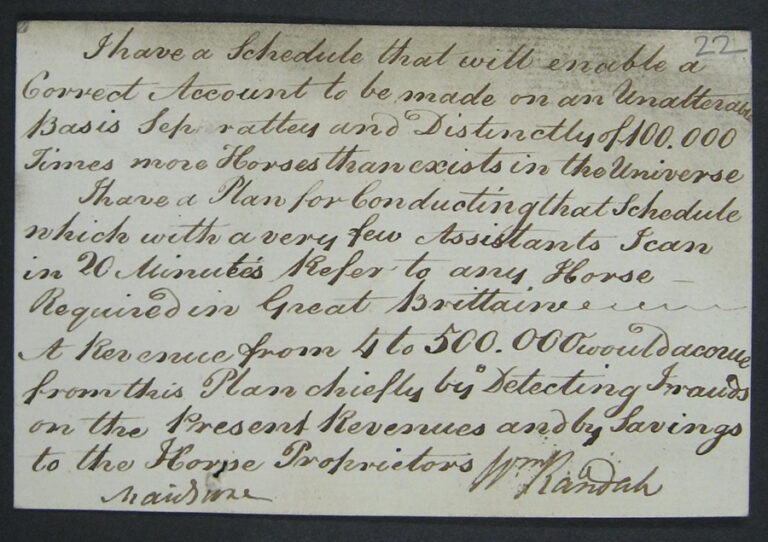

Another scheme proposed by William Randall of Kent concerns the listing and insurance of every horse in Britain, to prevent thefts and frauds, as well as raising funds for the Government (and himself).

The crisis continued with crop prices rising through 1799 to 1801. Attempts were made in both 1800 and 1801 to gain better information. In the summer of 1801, the Home Office sent printed forms to the Bishops who passed them on to the clergy, asking specific questions on acreage sown with wheat, barley beans etc. They received 5,000 returns which we have in record series HO 67, but when the Board of Agriculture examined them they again found that ‘they are so extremely erroneous that they cannot safely be at all relied on in forming any general conclusions respecting the quantities of land sown with any species of grain’.

It is thought that using the clergy to gather crop information made farmers suspicious, since farmers had to pay tithes to the church based on their produce, so they may have deliberately under-estimated their figures.

Having gathered information on food, horses, cattle and sheep, the Government realised that without relating these figures to numbers of consumers in Britain then such statistics were irrelevant. The Government needed to know how many people were in the country. The ‘Census Act 1800’, also known as the ‘Population Act 1800’, enabled the first census of England, Scotland and Wales to be undertaken. The first census was carried out in 1801 and every 10 years thereafter, although it was numerical only with no names or addresses being recorded until 1841.

Incidentally, the 1801 census estimated the population of England and Wales to be 8.9 million, and that of Scotland to be 1.6 million. Today, London alone has 8.9 million residents, and Scotland has 5.4 million people.

It could be said, therefore, that the half-hearted vagueness of the Duke of Portland, and his poor management of the food shortage crisis 225 years ago, gave rise to the creation of the Census, one of the main tools for genealogical research still in use today.

I remember well reading and transcribing some of the Home Office correspondence some years ago and the problems that the shortage of wheat caused and the lengths some people went to making the flour go further. Also the unrest it caused. One can only hope that people are not tempted to go that way again.

The manufacture of hand and hair power was banned ??? Hair powder?

The article about grain shortages is excellent and the facts are I believe wideky unknown,