I have always had a love of sport, especially football, and I first became interested in Walter Tull when I was trying to find possible football players listed in the 1901 Census (RG 13/296), which had just been released at the time. Following further research I found that he was from an underprivileged background, and was orphaned at an early age. He was one of the first black professional footballers, who suffered from racial bigotry at a time when racism was tolerated. He was supposedly the first black officer in the British Army at a time when the manual of Military Law forbade non-Europeans from becoming combat officers.

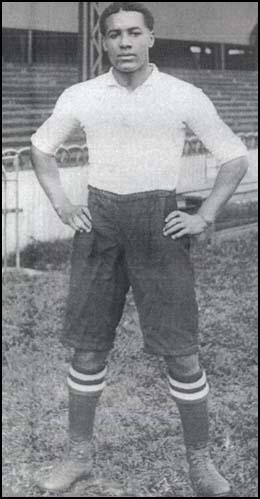

Walter Tull in his early footballing days with Tottenham Hotspur Football Club (with permission from Bruce Castle Museum -Haringey Culture, Libraries and Learning)

Walter Daniel John Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent, on 28 April 1888. His father Daniel came to Britain from Barbados in 1876, joined the Methodist Church, and in 1880 married a local girl, Alice Elizabeth Palmer, who bore him six children.

In 1895, Walter’s mother died. The following year, Daniel married Clara Palmer, but he then died in 1897. Clara was unable to cope with looking after all six children and consequently in February 1898 Walter and his brother Edward were sent to a Wesleyan Methodist orphanage in Bonner Road, Bethnal Green, where Walter spent seven years.

After finishing his schooling he served as an apprentice printer; but in October 1908, whilst playing for the children’s home football team, he was invited to join Clapton FC, a top amateur team. He helped them to victory as an inside forward in the FA Amateur Cup, the London Senior Cup and the London County Amateur Cup that same season. His promising talent attracted the attention of Tottenham Hotspur who signed him on for a fee of £7 in July 1908. While still an amateur, Walter was invited to tour Argentina and Uruguay with Spurs, signing him on as a professional on his return.

Walter was only the second black professional footballer in Britain, the first being Arthur Wharton, the Preston North End goalkeeper. He was the League’s first black outfield player, and attracted considerable media interest, being described as very good indeed with ‘a class superior to that shown by most of his colleagues’. Walter retained his place in the side at the start of the new season, appearing at centre forward in Spurs’ First Division debut, away to Sunderland, which ended in a 3-1 defeat. Walter’s future looked bright, scoring his first goal against Bradford, but then after only seven first team games he was dropped. This was probably as a consequence of the racial abuse he received from fans when playing at a game against Bristol City in 1909, which the Football Star called ‘language lower than Billingsgate’.

This unforgivable attack was laid at the door of the dockers and locals; and was influenced by Bristol’s 18th and 19th century reputation as a slave port. Whatever the reason it was an awful assault on a mild, intelligent and dedicated young man. Although there was no evidence that Walter’s confidence and form were affected, the incident was deeply traumatic for Tull, and rather than stand by their player, the Club’s directors were embarrassed by the whole debacle.

The following season he played only three first team games, scoring against Manchester City, and he was consigned to the reserves, where he played 27 times, scoring 10 goals. The season after, in October 1911 he was sold for a ‘heavy transfer fee’ to Northampton Town, an ambitious Southern League side managed by Herbert Chapman, an ex-Spurs player, who had no doubt about Tull’s background or ability. At Northampton Walter did not make an inspiring debut against Watford, and his early form was disappointing. However soon his career flourished at the club and he was probably their biggest star, having converted to a midfield role, to counteract his supposed lack of pace as a forward. He barely missed a game, completing 98 out of 114 games up to the outbreak of the First World War. There was much speculation that but for the war Walter would have signed for Glasgow Rangers.

Tull made a swift transition from sport to war. In December 1914, he abandoned his football career, and volunteered to join the British Army, enlisting in the 17th (1st Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, alongside many other professional footballers (WO 95/1361).

On 18 November 1915 Walter was posted to the Western Front, as part of the 33rd Division, 100th Brigade. Football helped counteract the boredom and monotony of life behind the lines, as many makeshift games were played. Soccer became an important feature of the men’s free time and was often seen as a galvanising force at others.

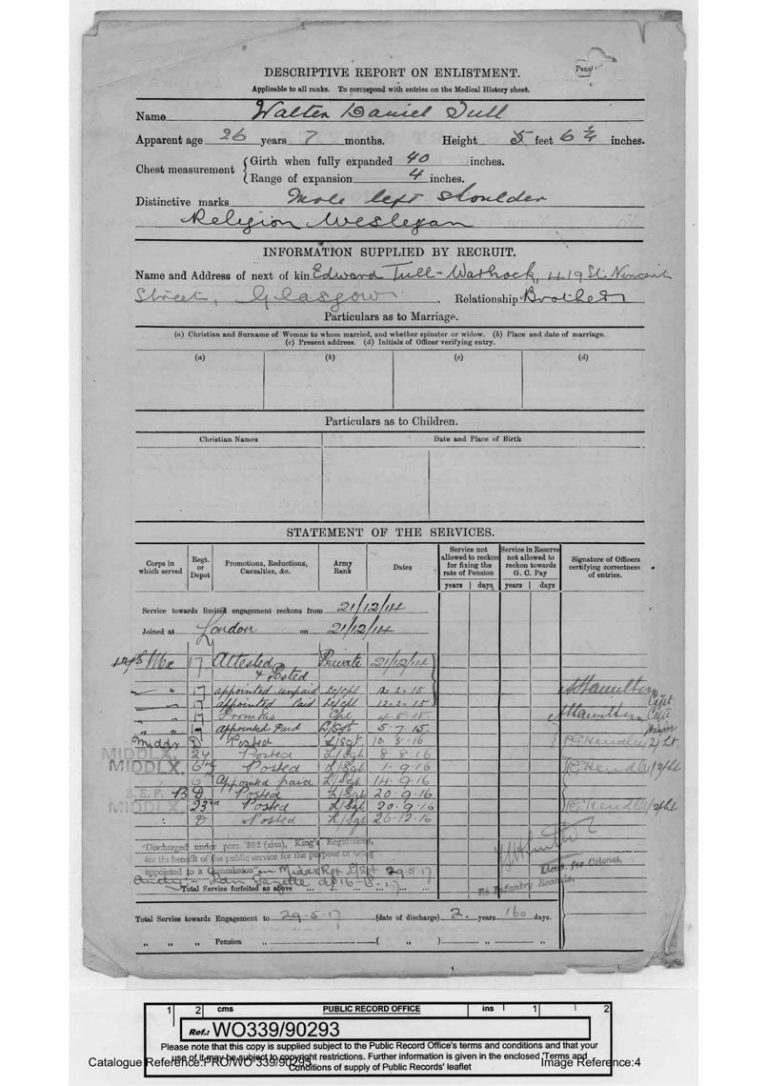

Walter Tull’s service record (catalogue reference WO 339/90293).

The dignity and strength with which Walter confronted blatant and vicious racism on the pitch were to serve him well on the battlefield. He was evacuated home with shell shock on 9 May 1916, returning to France on 20 September to fight in the 1st Battle of the Somme, where he survived the slaughter and was praised for his bravery. Walter showed he was a fine leader of men, receiving rapid promotion to Lance Corporal on 12 February 1915, to Corporal on 4 May 1915, then to Lance Sergeant just three days later.

With the mounting casualties the promising NCO’s were targeted as replacement officers and now something extraordinary happened. Towards the end of 1916 Walter was invalided home with trench fever. Upon leaving hospital on 26 January 1917 he was admitted to the officer cadet training school at Gailes in Scotland, to begin his training for a commission. This was unprecedented, indeed it was technically impossible. In general black officers did not command white troops and in the language of the time the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluded ‘Negroes’ from exercising actual command as officers. Yet Tull’s superior officers must have recommended him and, as a result of his service on the Somme, at Messines Ridge and Passchendale, he was commissioned in May 1917. He became the first black infantry officer in the British Army, although he was not the first black officer, as at least two were serving in the Medical Corps. Nevertheless this was quite some achievement.

According to his service record (WO 339/90293) and as a newly promoted 2nd Lieutenant he was posted to the Italian front with the 23rd (2nd Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, where he was mentioned in dispatches for his ‘gallantry’, ‘coolness’ and his ‘bravery under fire’ with which he led his men in the first Battle of Piave.

In 1918 he and his men were posted back to the Western Front, where they fought in the second Battle of the Somme. The end of the First World War was in sight but tragically Walter was not to see it. On 25 March 1918, the 29 year old was killed in no-man’s land, near Favreuil, whilst leading a counter attack against the German positions (WO 95/2639). His men held him in such high regard that they risked their own lives to try to retrieve his body, which was never found. Unfortunately the recovery had to be abandoned under increasingly heavy machine gun fire. For many years his only memorial was his name on a wall at the Arras Memorial set up by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Tull’s commanding officer reported to Edward Tull, in startlingly emotional terms, on ‘how popular’ he was throughout the battalion. He was brave and conscientious…..’The battalion and company have lost a faithful officer, and personally I have lost a friend’.

Society at large probably did not consider the untimely death of a black working class orphan a loss worthy of permanent commemoration, and he passed from the public mind. It was not until over 80 years after his death that a permanent memorial was unveiled, near the south car park, at Sixfields Stadium, the centrepiece for the Garden of Rest at Northampton Town Football Club.

The specific qualities that made him remarkable include many of the virtues traditionally viewed as appropriate for a British Army officer: modesty, dignity, honesty, quiet determination, courage – in short, a stiff upper lip. But he was loved for more than that – he was a figure of inextinguishable spirit, who was loved by Britons, black and white, and gave his life for his country. He must have been a remarkable man.

Walter’s true legacy is the influence and example he is for everyone today. Not just young footballers, not just young black people. Everyone! It took a very special person to surmount the barriers of class and colour and to establish themselves at the highest level in early twentieth century Britain.

May 1917 preceded Battles of Messines (June 1917) and what came to be known as Passchendaele (31 July 1917 through to November 1917) so it could not have been as a result of service in these campaigns that brought about his commission, which is what is implied. But otherwise an interesting article, thank you.

I would refer you to the work of Phil Vasili who is a recognised authority on this subject. He has published numerous books & articles on Walter Tull & Arthur Wharton. He made a documentary for the BBC on Walter Tull and has also written a play based on the life of Walter Tull which was shown on the BBC.

What a terrific article – thank you Richard.

[…] who played for Tottenham and Northampton Town, was Britain’s first black army officer to command white troops. He died aged 29 when he was shot on the Battlefields of the Western Front during World War […]

What a great but sad story well done

A great article on a whole – quite detailed and very engaging.

I was however slightly taken aback by the suggestion that Walter was remarkable because he possessed qualities “traditionally claimed as Anglo-Saxon [like] modesty, dignity, honesty, quiet determination, courage, in short a stiff upper lip.” These lines implied, maybe unintentionally, that these qualities were exclusively Anglo-Saxon and therefore Walter was not expected to possess them – although he did.

Walter’s father was an immigrant, so it is not difficult to infere that Walter would have picked up these qualities from his father, who can also be assumed to have come from a culture that traditionally shared these values.

To that end, i thought that part could have been better expressed replacing the word ‘claimed’ with ‘shared’ so that it doesn’t seem Walter, a blackman, exhibiting such qualities was extra-ordinary.

Hi David,

Thanks for your comment.

You’re right – this could have been phrased more clearly: I have edited the text accordingly.

Best regards,

Liz.

I have taken Walter Tull’s officer file out twice at TNA in the apst week and can find no trace at all of an MID in any document in it- let alone anything at all with the words supposedly quoted from it.

Could you please tell me where the reference is within the file so that I may come in again and check it