Methodologies is an exciting new event series by the The National Archives. It brings together researchers, practitioners, and creatives who generate new knowledge through the interrogation and disruption of archives.

In our event on 24 September we were joined by historian Corinne Fowler for Walking through countryside’s forgotten colonial histories. In conversation with historian (and Head of Collections Research at The National Archives) Philippa Hellawell, Fowler talked about her longstanding interest in the entanglement between rural landscapes and colonialism. She highlighted how she chose to use walking as a methodology to piece together hidden stories that help us deepen our relationship to the countryside.

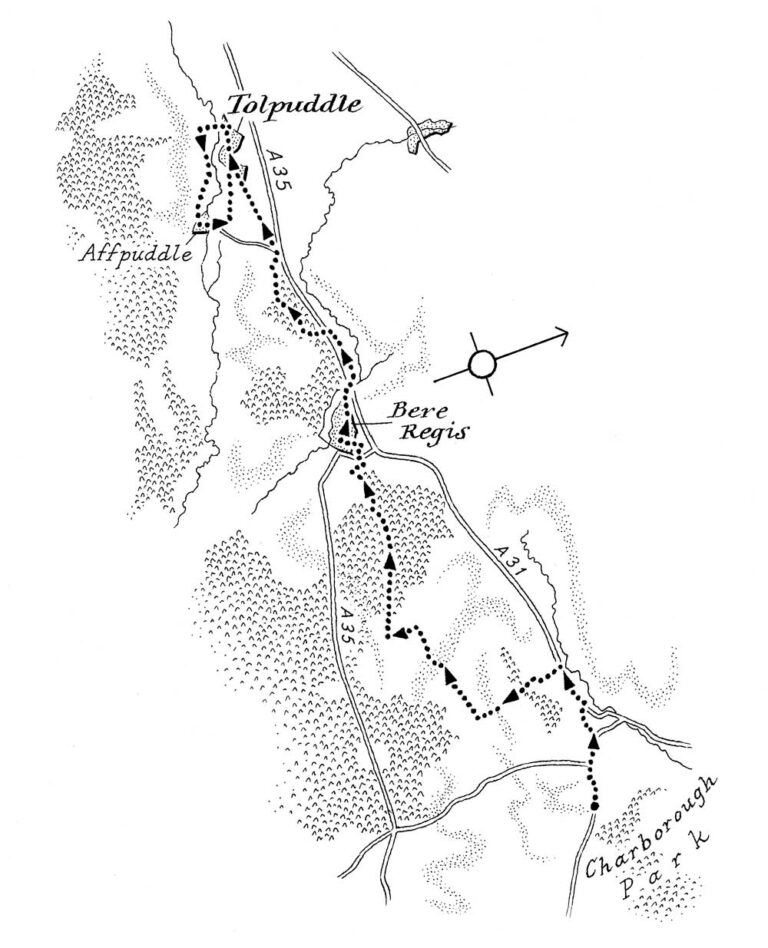

In her most recent book, Our Island Stories: Country Walks Through Colonial Britain, Fowler embarks on ten walks through the idyllic British countryside to reveal its forgotten links to transatlantic slavery and colonialism.

Inspired by this, I invited historians (and collections experts) Philippa Hellawell, Elizabeth Haines and Chris Day to join me to re-enact one of Fowler’s walks… In the archive.

Over three blogs, I will explore the spatial dimensions of The National Archives’ historical records and how they relate to the physical-historical space walked and explored by Corinne Fowler. In the process, I’ll experiment with an alternative, more creative methodology for historical research.

Many kinds of space

Space in an archive can manifest in different ways: physically, space is the space occupied by a record. This can be the space taken by the unfolded document on a table, the box containing a record on a shelf, a repository, a reading room.

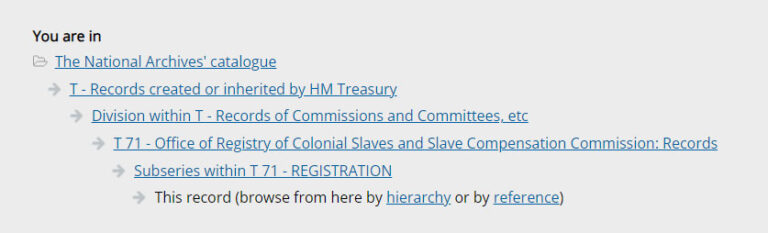

On a more abstract and virtual level, space can be the location of a record in the catalogue. When we find a record in The National Archives’ catalogue, Discovery, we can ‘navigate’ the hierarchy and see where the record sits, or has been seated, within the broader arrangement of the archive. ‘You are here’ refers to where the record page fits into the catalogue hierarchy.

A record traverses space when it is brought from a repository to a requester’s shelf by a member of the Document Services team. That same team has previously translated the record’s virtual catalogue location into a physical one. Similarly, space is what connects the requester’s shelf to a consultation desk.

Space can also be the page of a website. A blog post like this is a space where, like on a map, we can represent space through graphic conventions.

Space is clearly an important element in archives. Walking it can represent, as Professor Fowler demonstrates in her book, a way to thread together stories which at first sight don’t seem connected, but instead are deeply intertwined. Similarly, walking and traversing the space of the archive is a way for us to bring records close together when they would otherwise sit on separate shelves.

Moved by this exploratory intention, I decided to try to follow one of Fowler’s walks with my colleagues at The National Archives to see what this exercise could bring to light. In the process, we could reflect on how space can be a creative research methodology to bring together records from different collections and historical periods.

So here we go! Join me, Philippa Hellawell, Elizabeth Haines and Chris Day on “The Labourers’ Walk: Tolpuddle and British Penal Colonies” at The National Archives. Please note that it refers to violence and dehumanising treatment towards enslaved people in Barbados.

Before we start, to enhance your experience, you might want immerse yourself in this archive walk soundscape. Think footsteps, photocopiers and trolley noise…

First stop: Charborough Park, Barbados, with Philippa Hellawell

Fowler’s walk starts at Charborough Park in Dorset, where a 17th-century manor house can still be admired. She is joined by Louisa Adjoa Parker, a writer of British-Ghanaian heritage.

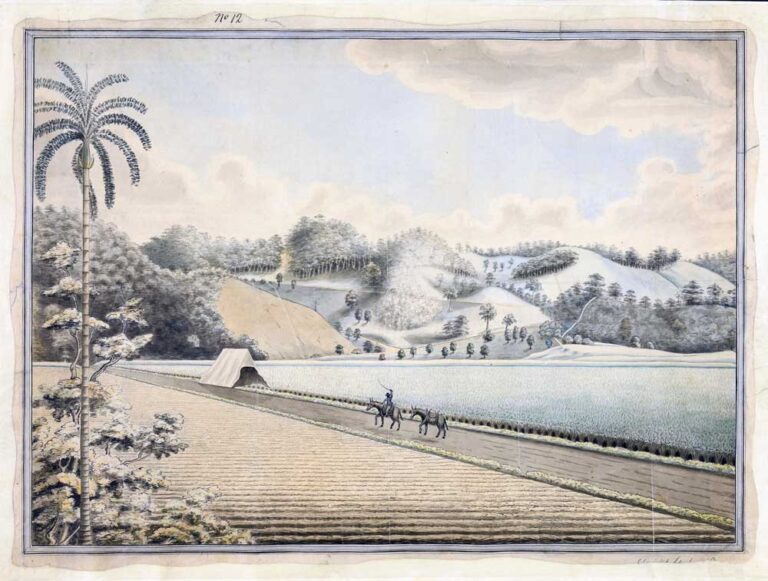

Owned by the Erle-Drax family, the house at Charborough was built within a few decades of the erection of Drax Hall in Barbados, a plantation owned by the family where enslaved people cultivated sugar cane.

Our journey at The National Archives starts among records related to Barbados, and I am joined by Philippa Hellawell, a specialist in colonial and maritime records. She has chosen two records that capture the inhumanity of chattel slavery in Barbados, which has a dark history also embedded in the Dorset countryside.

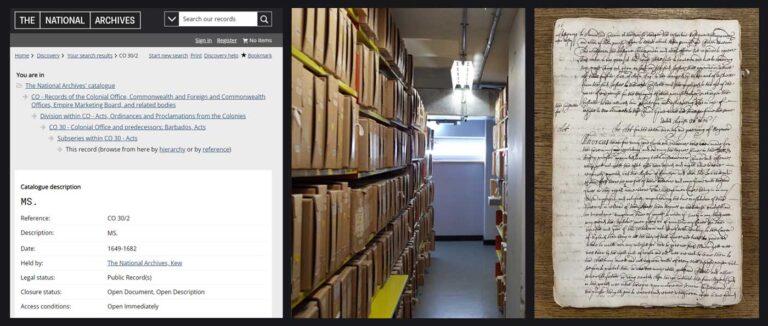

Record CO 30/2 f16 – Barbados, Acts

Philippa: Barbados had become the largest slave economy in the English empire by the late 17th century. Sugar was the main commodity cultivated through the enslavement and exploitation of approximately 40,000 enslaved Africans on the island.

From the perspective of colonial administrators, these large enslaved populations posed a threat to the security of white colonisers. Strict laws were developed to govern, manage, control and coerce enslaved populations, which was enshrined in the Slave Code of 1661. The code included provisions to limit the travel of enslaved people, punish them with whipping for any violence against Christians, search their houses for weapons and runaway enslaved people, and try those who engaged in rebellion or insurrection under martial law.

Officially titled ‘An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes’, the Barbados slave code shown here acted as a model for similar sets of coercive laws across the English, and later British, empire.

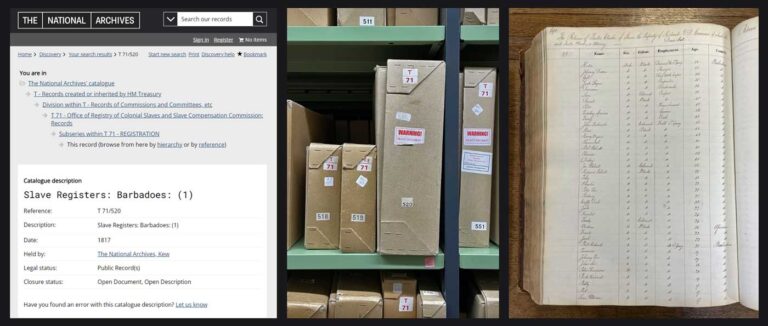

Record T 71/520 f81 – Slave Registers: Barbados, Drax Hall

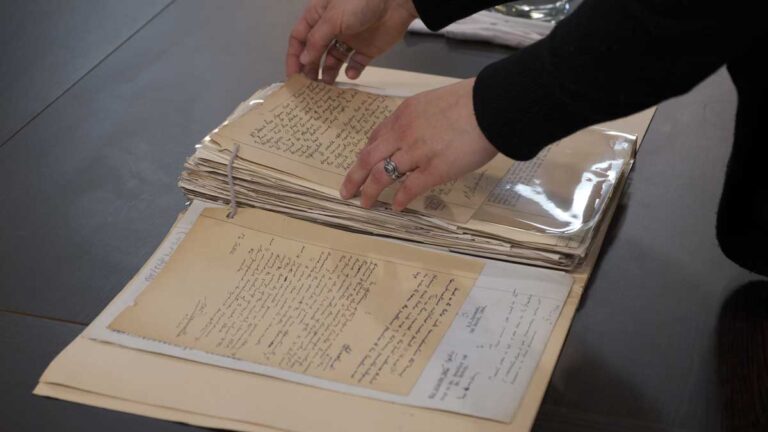

Philippa: Drax Hall was a plantation in the parish of Saint George, Barbados, under the ownership of Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor in the early 19th century. This is a register of enslaved men, women and children at Drax Hall in 1817, which provides information on their name, age, employment and whether they were African or Barbadian born.

There were 154 enslaved people at Drax Hall in 1817. The eldest were 73-year-old Mimbah Orion, listed as a ‘calf keeper’, and 73-year-old Mary Goppy, who was described as ‘infirm’. Both were born in Barbados, having never known their ancestral homeland. Ten of the enslaved children at Drax Hall in 1817 were under one year old.

Registers were often compiled every three years, noting any increases and decreases in enslaved populations on each plantation. Populations were being monitored in the wake of the abolition of the trade in enslaved people and the ban on importing enslaved people (plantation slavery itself was not abolished until 1833). While these registers served as bureaucratic records, they offer some of the few and limited insights we have into the personal details of those whose freedom was stolen from them.

Continue our walk in Part 2

I hope you’ll join me for the second part of my walk as we continue to Tolpuddle, and explore connected topics including the birth of trade unionism and the Royal Prerogative of Mercy…

The Pennants Heritage Group based in Pennants, Clarendon is researching in the Bangor University Archives.

We are exploring the story of the Welsh Pennant family including the Lord Penrhyn’s who used the wealth generated on their plantations in Jamaica to build the flamboyant folly of Penrhyn Castle, now a National Trust property with hardly a mention of the owners enslaved workforce.

Sorry, but this concept of “space” is of no help or interest. If you were to take an archival map or personal recollection and actually visit the site (space) then knowledge could be considerably widened.

Thanks for all your efforts and service.

Rather than just focusing on history from the English mainland, it’s wonderful to see the ties that bind archival research to those of us whose families immigrated to the colonies. Whether it’s slavery in the Carribean, the penal colony in Australia, the settlements in Africa and India, as well as from the workhouses to other foreign lands such as Canada, there’s a wealth of valuable stories to be told. I look forward to seeing our ancestors recognized for the hardships they encountered and overcame, to make better lives for their descendents.