ZSPC 11 is the record designation at The National Archives for a varied collection of material about railways representing, in effect, the life’s work of Wilfrid Edwin Hayward, an engineer and railway enthusiast. The collection consists mainly of magazine cuttings, photographs and postcards, published booklets by, or about, the railways, tickets, and railway forms and leaflets including timetables.

What’s in the collection?

In The National Archives’ cataloguing rules, the ‘Z’ in ZSPC implies that the contents consist of published, or ‘library’, material but in the case of the Hayward collection, that isn’t completely true. For one thing, much of it is not on paper; there are objects too, some of them rather extraordinary – more on that later. Furthermore, some of the paper documents are original records; letters from railway companies, filled out railway forms and returns, and letters between Hayward and the railways and other collectors which tell us about Hayward himself and the world in which he lived.

The volunteer cataloguing team

ZSPC 11 consists of Hayward’s railway library of over 270 volumes, and more than 420 binders and albums of his collected material. A team of five is cataloguing the contents of the binders and albums item by item. The current team includes a former head of the British Transport Historical Records office (BTHR), two members of The Friends of the National Railway Museum, one from the Great Western Railway Study Group and me, at one time the Public Record Office’s records inspector for British Rail.

We are currently 85% of the way through cataloguing the binders. The initial impetus for the project was the need to catalogue the thousands of photographs stored loosely in the binders, but, while we are at it, we catalogue everything and give each item a unique reference.

Arrangement of material

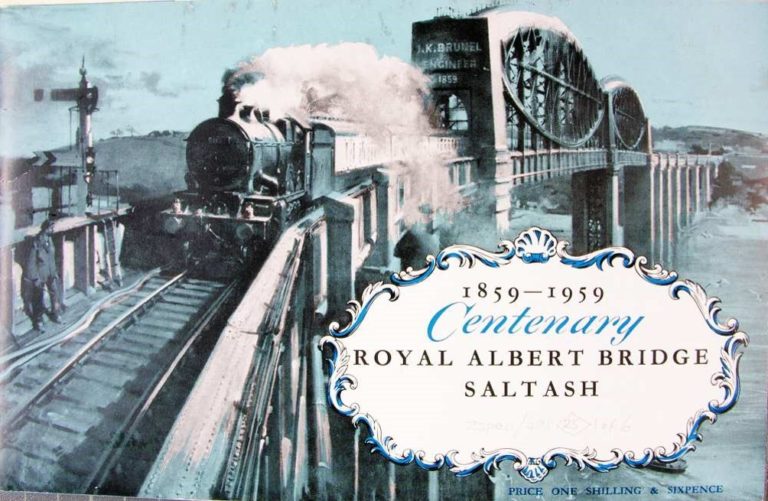

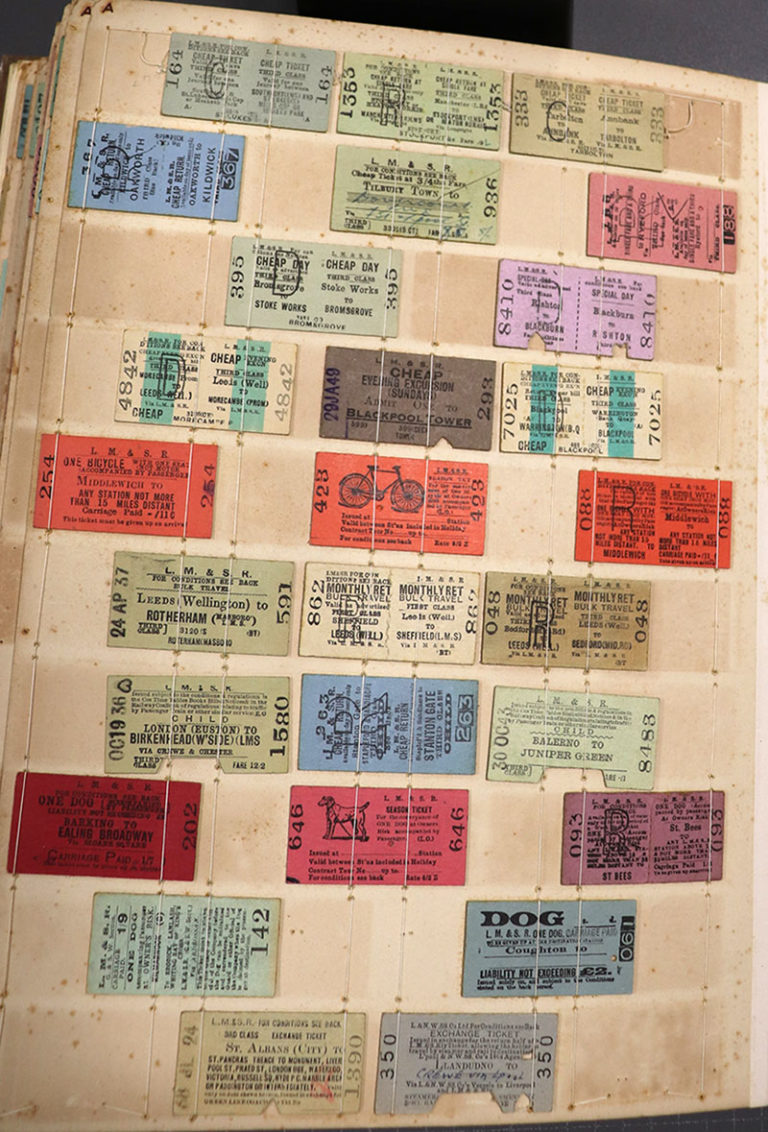

Hayward’s work in collating, mounting and securing material in the binders is astonishing. From periodicals and newspapers he cut articles and illustrations relevant to all and any railway he came across, and reassembled them in separate sections for each railway, adding photographs, tickets etc according to a standard order. For each railway there is usually a section of general history articles, followed by sections describing the route(s), locomotives and rolling stock, each with photographs and tickets where appropriate.

This feat of organisation was guided by an overall arrangement scheme: miniature and minor railways, England; general details about locomotives and general railway techniques, construction and administration; industrial railways (collieries, iron works etc), overseas railways and locomotive building companies; major railways, England; Scottish railways; Irish railways; Welsh railways; and finally a section dealing with underground, and unusual railways, three of the ‘Big Four’ grouped railways 1923–1948, and two binders on nationalised British Railways.

Hayward, an engineer after all, had a good understanding of materials and those he chose to use in preparing the collection have survived extremely well. He must also have devoted a huge amount of time to stitching, marking out, gluing and typing.

Who was W E Hayward?

What we know about Hayward comes mainly from the contents of the binders, but some useful information has also come from the Family History Association in Weston-super-Mare, where he lived most of his life. He was born in London in 1890 and died in 1968 in Weston. His father was a sub-inspector of schools whose work had taken him, by 1900, to the West Country, where the 10-year-old Wilfrid was photographed by his father standing in front of a railway carriage newly-landed at Bideford quay for the opening of the Bideford, Westward Ho and Appledore Railway.

His father died in 1902. In 1906, Hayward’s mother tried to secure him an engineering apprenticeship in one of the locomotive departments of railway companies. She was not successful: we have found rejection letters from the Chief Mechanical Engineers of the Great Western, London and South Western, Great Eastern and Great Northern Railways in the collection.

Eventually Hayward took up a four-year apprenticeship with the Avonside Engine Company, Bristol, and in the collection are many mementos of that, including a blueprint copy of his first technical drawing. The collection also contains a good deal of his research material on the locomotives produced by Avonside.

His subsequent career is still something of a mystery, though Hayward says he was ‘…then engaged in engineering, mainly in the shops, until poor health obliged me to give up earlier than usual’. In 1931 he lost his left eye in a metal piercing accident which, presumably, was the cause of his retirement. After that, he appears to have devoted himself to collecting. Although a short article in the ‘Weston-super-Mare Mercury’ says he did not begin to organise the collection in its present form until 1941, there is also a note that he first intended to systematise it in 1925.

Donating the collection

Hayward was proud of his unique collection and, after several approaches to institutions, it was agreed, in 1957, that it would be deposited in the British Transport Historical Record Office (BTHR).

There are three binders devoted to the correspondence about the deposit; they include copies of the codicil to his will by which Hayward made the bequest. Letters show him to be somewhat tetchy, inclined to stand on his dignity, but usually compelled to back down in the end. This is hardly surprising, perhaps, since his health was failing and the sight in his remaining eye was deteriorating.

In earlier correspondence, he shows that he was a generous collector, offering payment for material supplied him. He formed friendships with railwaymen, who would pass to him items no longer in use by the railway, and he donated to railway benevolent institutions.

He also had contacts among other railway collectors, most notably with T R Perkins, chemist of Henley-in-Arden, who was said to have ridden over every line in the British Isles and who passed over many things from his own collection, including some of his and his father’s photographs.

Cliff,

According to the General Register Office indexes his birth was registered in the October-December quarter of 1889 and the Census says he was born in Stoke Newington in London. The 1911 Census says although he was an engineer, but at the time he was unemployed. There were three children of his parents but one had died.

David

Enjoyed reading this – got the link off Tim Dunn’s twitter feed!

Well done team, a valid labour and worthy of any such collector.

from and on behalf of the Ballast Trust volunteers labouring in Scotland.