Research Libraries UK and The National Archives offer a Professional Fellowship Scheme, allowing staff the time and resources to focus on a research project with the support of knowledgeable mentors across both organisations.

Fellows explore a professional practice question, develop new skills and knowledge, and share their learning with members of Research Libraries UK and The National Archives. This year we awarded two fellowships, which we’ll explore in a short series of blogs.

The first fellow to share their work is Karen Sayers. Since 2011, Karen has been an archivist at Leeds University Special Collections, with a wide-ranging remit including cataloguing, acquiring new material, and supporting internships. Her research interests are in medieval history and local studies.

Here Karen describes the work her fellowship has enabled, developing a Toolkit for Archivists and Librarians Supporting Research and Teaching in Digital Humanities.

– Lily Colgan, Academic Engagement Officer, The National Archives

The professional practice question I focused on for my Fellowship was the use of historical record series as data. I wanted to identify resources to enable archivists to support researchers and academic staff carrying out digital humanities projects using data from archives.

I decided that the best way to do this was to become a researcher and undertake a mini digital humanities project. I chose to extract data from the Wakefield Court Rolls from 1331–32 and use it to create visualisations to reveal aspects of medieval life to a wider audience. My project, ‘Visualising the Medieval Manor’, was born.

Data Sources

The Wakefield Court Rolls are a rich source of data about people’s lives on the Manor of Wakefield. From a time when the experiences of ordinary men and women were rarely recorded, the court records provide an insight into their daily lives. They contain data about the cases brought before the court, including people’s names, dates, fines, and types of action.

My first step was to identify digital humanities projects that had analysed historical record series. Some have websites such as the Witches project and Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade, with visualisations and searchable databases. Projects like these gave me inspiration for what can be achieved with data.

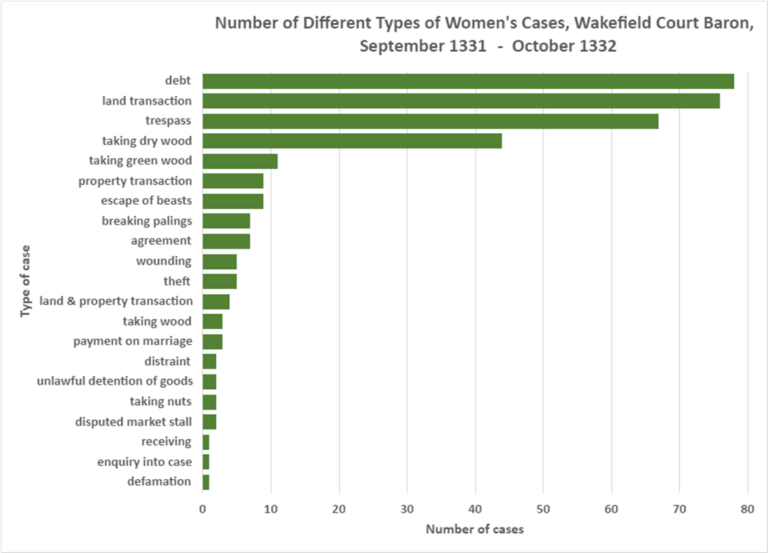

The Wakefield manorial court rolls 1331–32 are a data-rich source. My first decision was what data to extract. I wanted to find out more about women’s lives and the types of offences or legal claims they were involved in, so I gathered data relating to cases which mentioned women.

Extracting Data

The rolls have been transcribed and uploaded to the Internet Archive, but the inconsistent punctuation, spelling of names and the way women are identified meant it was difficult to extract the data into structured columns in a spreadsheet. For example, women are often referred to as ‘wife of’ or ‘handmaid of’ rather than by their own name.

The ‘handmaid of John Harillul’ is one such unnamed woman. I decided to read the data, select relevant information, and input it into the spreadsheet. Processing the data was not going to be as straightforward as I had hoped!

| Date | Person | Type of case | Position | Action | Fine in pence |

| 18/10/1331 | Cecily Hudelyn | debt | plaintiff | compromise | |

| 8/11/1331 | Christine de Aula | debt | plaintiff | compromise | |

| 8/11/1331 | Alice Leulyn | trespass | defendant | amercement against | 6 |

| 8/11/1331 | Agnes Peger | trespass | defendant | amercement against | 2 |

| 8/11/1331 | Emma Bilton | trespass | defendant | amercement against | 24 |

| 8/11/1331 | Alice wife of Robert | detinue (action to recover possessions) | defendant | unresolved | |

| 8/11/1331 | handmaid of William Michel | theft of dry wood | defendant | amercement against | 2 |

| 8/11/1331 | daughter of John Nelot | theft of dry wood | defendant | amercement against | 2 |

| 8/11/1331 | Agnes Hogg junior | theft of dry wood | defendant | amercement against | 2 |

| 8/11/1331 | handmaid of Thomas Preest | theft of dry wood | defendant | amercement against | 2 |

Standardising Data

I standardised the data by removing or correcting wrongly formatted, duplicated or incomplete entries. In the medieval period the spelling of surnames varied. Importing the spreadsheet into OpenRefine to use its facet option was helpful as I could compare similar surnames, such as Agnes Bul and Agnes Bull. I was confident that these were the same person and combined the entries.

I learned from experience and other researchers that cleaning data often takes more time than gathering it. However, software packages can only interpret and visualise clean data. Cleaning also avoids spurious results from incomplete or incorrect information.

On reflection, I realised that I had developed many of the skills required for gathering and recording standardised data from historical record series through my archival cataloguing work. For example, I have recorded and cleaned metadata in spreadsheets and imported it into a collections management system to create catalogue records, which was useful experience.

Visualisation Software

I found mastering the terminology and some functions of data visualisation software packages the greatest challenge. I prefer in-person courses, but accessed online learning resources for PowerBI and Tableau Public because they were easily available. Some previous training on quantitative methods, although rusty, helped. I created basic graphs from data on women’s cases and found that the most effective visualisations are simple.

Conclusion

I found my fellowship rewarding. The greatest challenge was finding time to master the range of skills involved in a digital humanities research project, including extracting and cleaning data, and learning to create visualisations. I concluded that most projects are best undertaken by a collaborative project team combining their skills.

Archivists can be valuable contributors to, and partners in, digital humanities projects, sharing their metadata skills and collections knowledge. My Toolkit for Archivists and Librarians Supporting Research and Teaching in Digital Humanities is now available.