The Admiralty China Station, a British Royal Navy command, operated in China and the Far East from the mid-19th to mid-20th century, safeguarding British interests in the Far East. It played significant roles in the Opium Wars, Boxer Rebellion, and both World Wars. The correspondence series from the Station headquarters (ADM 125) is a valuable but underutilized resource for exploring regional history.

To improve access to ADM 125, Yannick Signer, a PhD candidate at the University of York, completed a three-month placement at The National Archives. During this period, Yannick used a Digital Humanities approach to uncover lesser-known histories of the region. Yannick’s blog highlights the use of social network analysis to visualize the changing communication networks of the China Station, providing a springboard for targeted examination of specific communications.

– Padej Kumlertsakul, Adviser for Overseas and Defence, The National Archives

Cataloguing correspondence

In order to visualise and investigate the China Station correspondence networks, nine volumes from the ADM 125 correspondence series were selected for cataloguing. This focused primarily on recording individual letters, many of which enclosed further correspondence and were grouped by specific topics.

For each letter, the corresponding people, the dates written and received, and a summary of the content were collected to enhance their entries in the Discovery catalogue. Identifying who wrote a particular letter was sometimes challenging as signatures proved difficult to decipher, but with some additional research (such as cross-referencing with other entries in Discovery), many of the correspondents could be identified.

Some of the letters also contained unusual enclosures, which included plans of dockyard extensions, copies of diary entries, sketches of surveyed islands, illustrations of naval docking facilities in foreign ports and photographs.

Overall, close to 3,500 pages of correspondence were examined and catalogued, which resulted in over 800 items of correspondence that could be used for the analysis and visualisation part of the project.

Visualising and examining correspondence networks

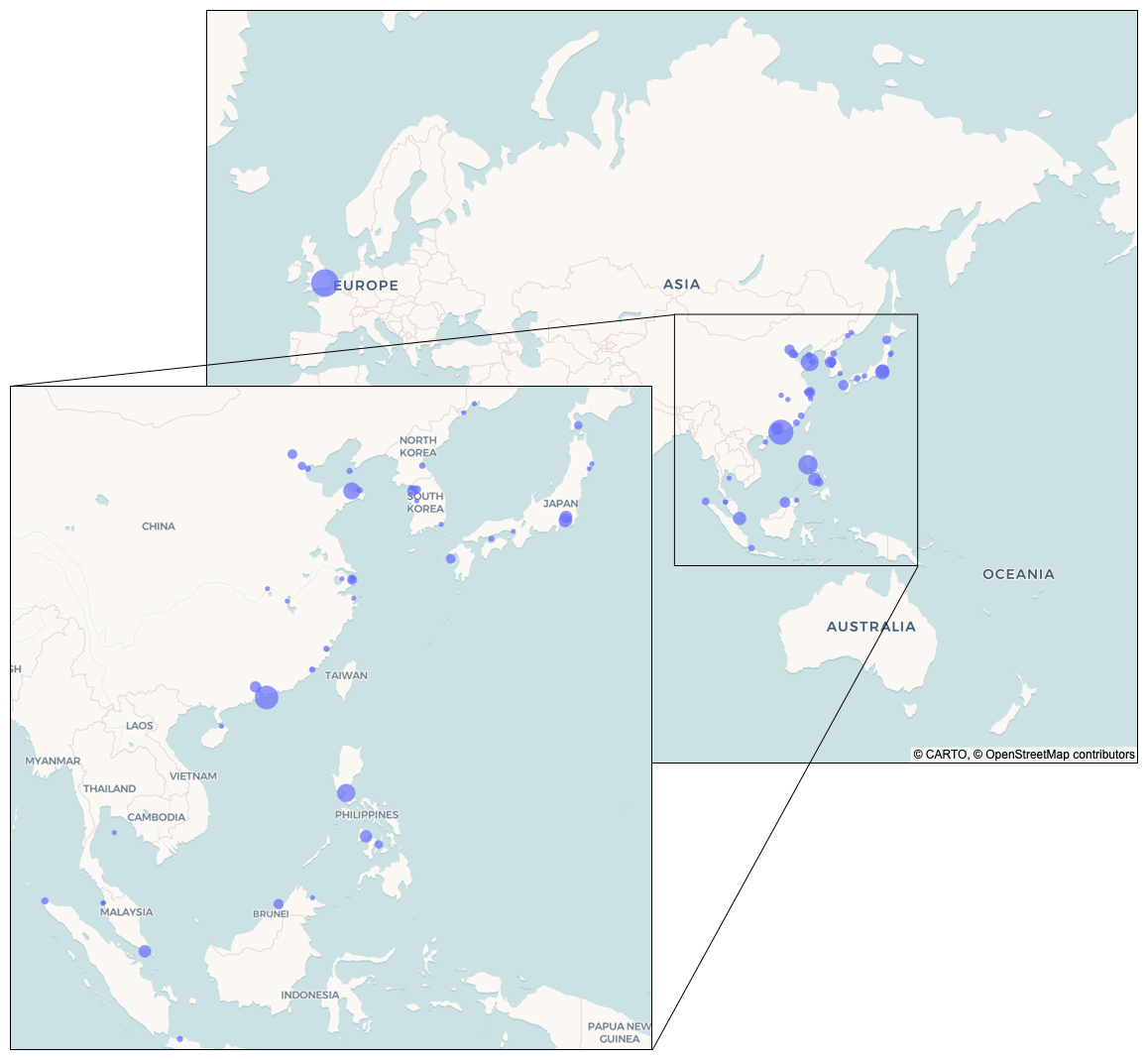

One of the key aspects of this project was to examine the spatial dimension of the China Station communication networks. To explore this, it was crucial to identify as many places from which letters were sent as possible. This proved to be tricky at times as most places were given as non-standardised spellings of Romanised variants of Chinese place names.

Luckily, some great research resources are available online to help with this, such as the 1903 China postal working map, which shows the location of many of these Romanised place names. With such resources, the origin of all examined correspondence received at the China Station could be identified and mapped (Figure 1). Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of the correspondence received was from within China Station’s area of responsibility and from the Admiralty headquarters in London.

The distribution of correspondence can also be examined across time, and as such, an animation has been created that shows the number of correspondences received from different places that year (Figure 2). This highlights the shifting of correspondence in alignment with broader geopolitical events. For example, during the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, more correspondence was received from near the Korean peninsula.

However, as not all available correspondence for these time frames was catalogued, these spatial trends are incomplete, but highlight that additional cataloguing and examination will likely allow more nuanced trends to be identified and potentially correlated to shifts in British interests in the region.

Social networks of China Station correspondence

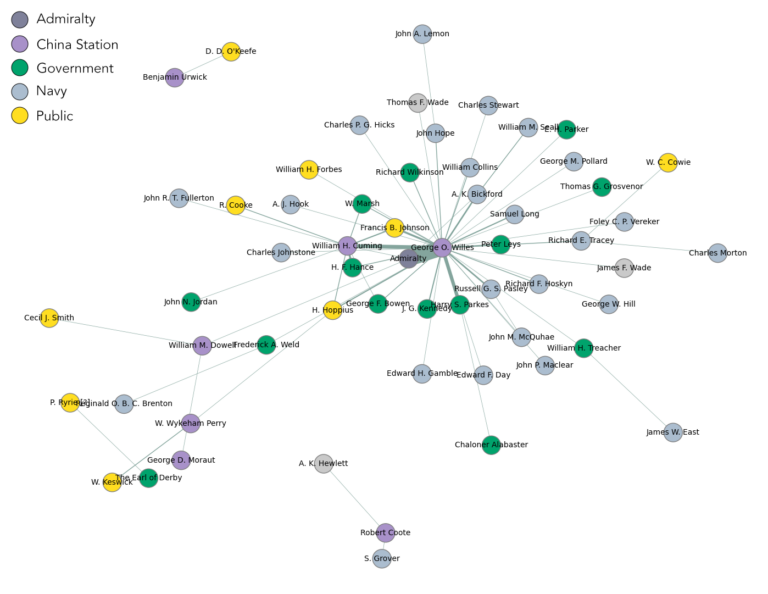

Beyond the spatial networks, the data also allows us to examine the social networks apparent in the correspondence. Such a network can be established by connecting individuals who correspond with each other with a line. By repeating this for all of the letters in the catalogued correspondence volumes, we can see who communicated with who the most, with thicker lines representing a higher frequency of correspondence. Over 150 correspondents have been identified, resulting in complex and visually busy networks. In order to simplify these, the following networks have been limited to specific year ranges.

The first network created is based on the correspondence of the China Station from 1881–1884 when Vice Admiral George O. Willes was Commander-in-Chief (Figure 3). Out of the nine volumes dating to this period, six were catalogued, providing a detailed (albeit incomplete) insight into the communication network of the China Station during these years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the resulting network shows both the Vice Admiral and the Admiralty at the centre, highlighting their centrality to the correspondence and the strong link between them.

Correspondence from different groups (the Navy, governmental representatives and public individuals) all communicated directly to the Vice Admiral (who usually forwarded such correspondence to the Admiralty for consideration). Interestingly, while the Commodore (the second in command of China Station) William H. Cuming is also fairly central to this network, he was seemingly less involved with correspondence to and from the Navy and the Admiralty, possibly highlighting the rigid command hierarchy of the Royal Navy at the time.

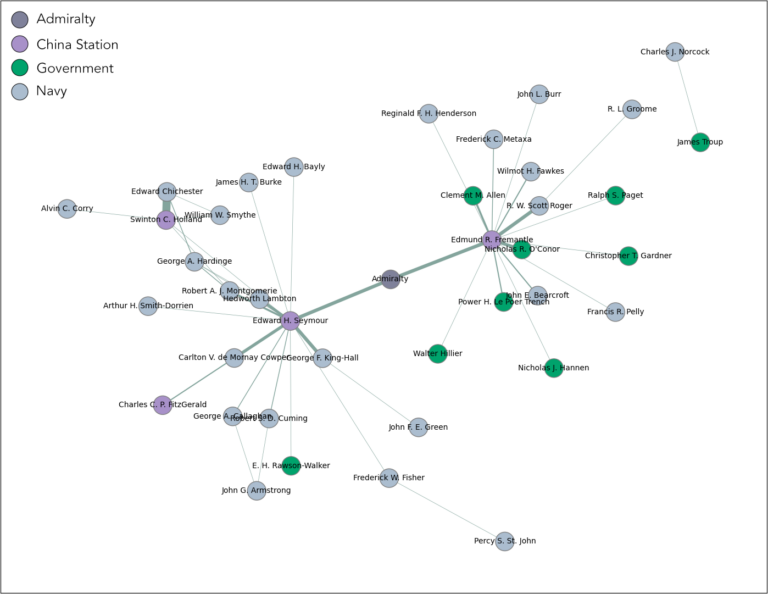

The second network (Figure 4) is based on some of the correspondence to China Station under the command of Vice Admirals Edmund R. Fremantle (during the First Sino-Japanese War) and Edward H. Seymour (during the Spanish-American war and the subsequent Philippine Rebellion). The correspondence during these two conflicts is quite different, with Fremantle being in much more contact with governmental representatives (mainly consular and colonial agents) than Seymour. This most likely relates to the fact that the Sino-Japanese War led to much more consular activities in the Chinese ports (where many consulates were located) than during the conflict in the Philippines, where Britain’s interest was only marginal.

Additionally, Seymour’s Commodore (Swinton C. Holland) communicated much more with some Naval staff than the Vice Admiral, potentially highlighting a delegation of responsibilities during this conflict.

These correspondence networks are a great way to visualise the changing communication networks of the China Station and can also be used as a springboard to target specific parts of the communication for further examination.

Future potential

This small pilot project has highlighted the great potential of the information contained in the Admiralty China Station correspondence and has shown that their study could provide new perspectives on large-scale geopolitical events taking place in the area.

The analysis conducted on the partial dataset has also revealed the potential of these records to provide insight into the spatial and social side of correspondence networks. The cataloguing of additional volumes and collecting of more data points would give more insight into how these networks changed with the shift in priorities of the station.

It would also be interesting to enhance these networks with further correspondence from outside the China Station, for example incorporating related Foreign Office correspondence or letters from other naval stations, or focus on the content of individual letters, such as analyse of their content through sentiment analysis.

Thank you for your fascinating visual networks of correspondence. It’s extremely helpful and illuminating to have a visual representation of this correspondence. I would love to see similar graphing of later correspondence e.g. during the first and second world wars.

I have a photo of the China Squadron, from around 1934. It would appear most of the ships assembled would be anchored off Wei-Hai-Wei

It would be interesting to know how much of the correspondence is replicated in the relevant boxes of ADM 1.