Ruth Selman, from our Advice and Records Knowledge Department, and Lucy Angus, formerly of our Collection Care Department, describe their respective roles in preparing documents for display at an event.

An unexpected discovery

Ruth: When I opened the grey box in our Invigilation Room, I was expecting something decorative but I wasn’t expecting to be bowled over by the vibrancy of the illuminated manuscripts housed inside.

In preparation for a study day on Rawdon Brown and the Anglo-Venetian Relationship to be held by Venice in Peril and the British-Italian Society at The National Archives, it was my pleasant duty to identify a selection of documents which demonstrated the breadth of our holdings of Venetian archives. Rawdon Brown had the enviable job of working for the Public Record Office while living in Venice in the 19th century. He scoured the archives of Venice for material casting light on English history, producing material for the ‘Calendar of State Papers Venetian’ in the process. He was an avid collector of manuscripts as well and we were fortunate enough to receive his collection as a bequest in his will.

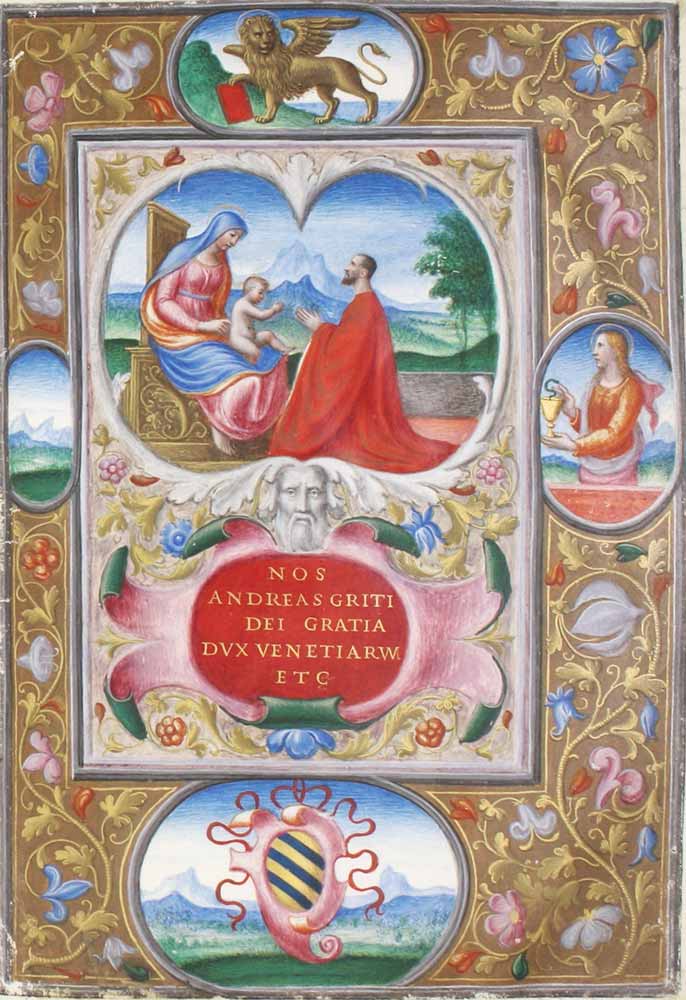

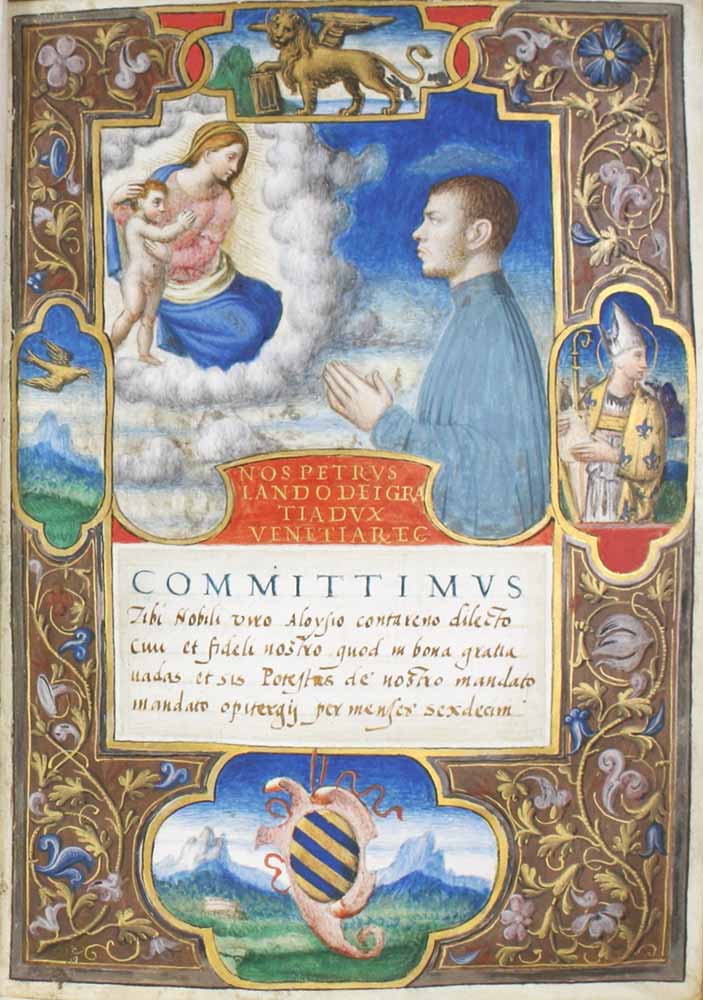

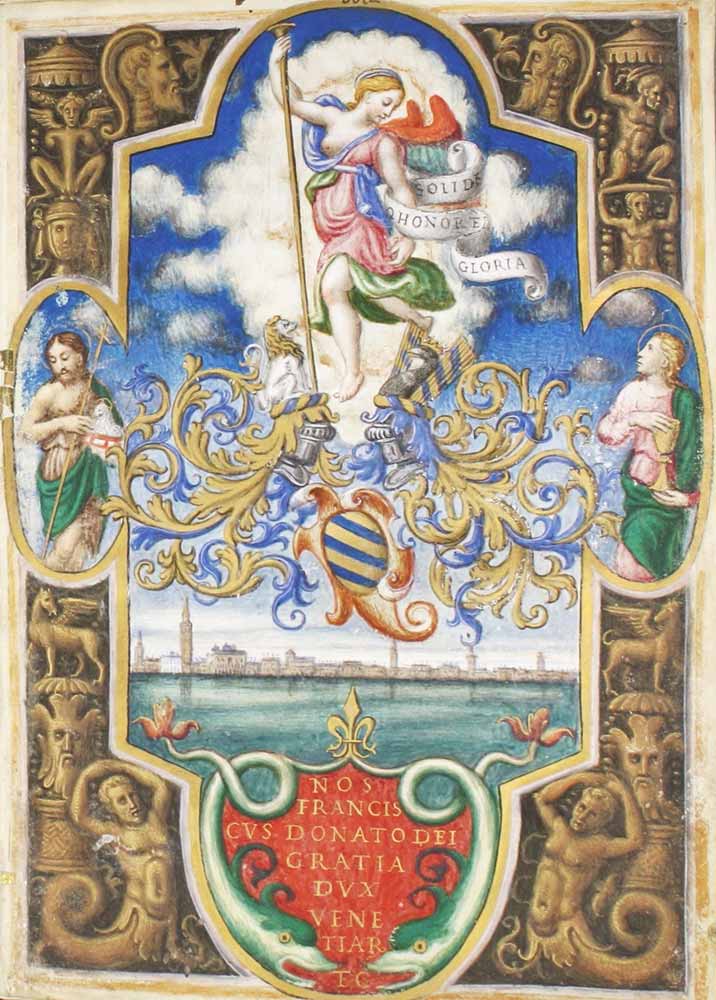

The collection (in record series PRO 30/25) is extensive and represents a major resource for studying the history of Venice. My eye was caught by the full descriptions of the documents in PRO 30/25/104; a collection of Ducal Commissions or ‘Commissioni Ducali’, these documents are a little-known treasure. They are each a unique representative of an ornate type of formal document which became highly collectible by the 19th century and thereby have made their way into many collections worldwide. The four displayed below were all given to members of the Contarini family by the Doge of Venice on their appointments to public office and the illuminations form the frontispiece for extensive descriptions of their roles and responsibilities in Latin.

Three of the illustrations depict the appointee; it is possible to see faint signs of aging in the later of the two showing Alvise Contarini – his hairline is receding and his eyes are a little more tired. Their namesake saints are also included, as are representations of Venice, including the lion of St Mark and one- and two-tailed mermen.

- Alvise Contarini, Governor of Oderzo, 14 Aug 1543 (catalogue reference: PRO 30/25/104/5)

- Alvise Contarini, Governor and Captain of Bassano, 7 Jan 1550 (catalogue reference: PRO 30/25/104/8)

The commission appointing Bertuccio Contarini as governor of Cittadella in 1548 takes a different approach by depicting a cityscape of Venice instead. It is composed looking from San Giorgio Maggiore towards the Riva degli Schiavoni and appears to be a relatively careful depiction of reality. St Mark’s campanile can be seen on the left. To its right is the Doge’s Palace with the domes of St Mark’s peeking above its roof. The typical tall Venetian chimneys bristle above the roof tops.

Bertuccio Contarini, Governor of Cittadella, 1548 (catalogue reference: PRO 30/25/104/7)

Having swiftly decided that we had to display these documents during the study day, I asked colleagues in Collection Care for their advice. Lucy Angus takes up the story.

The conservation – behind the scenes

Lucy: My first step was to check the condition of each document and decide if they would need conservation treatment.

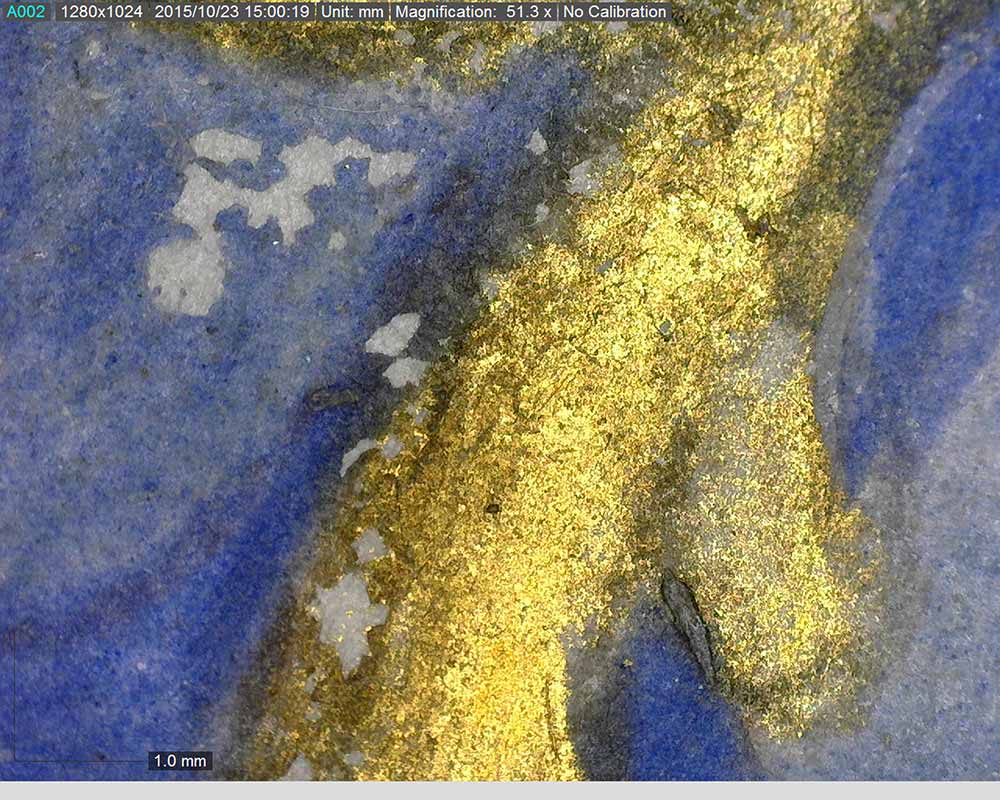

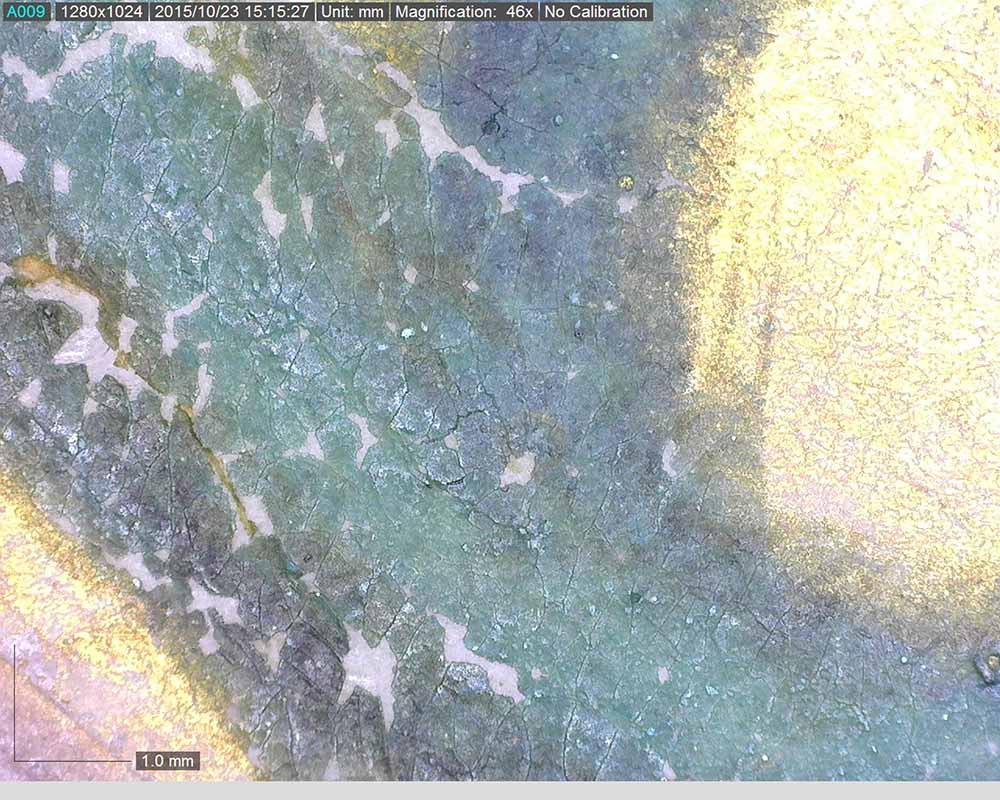

Due to the behavioural characteristics of parchment the paint layers are vulnerable. When parchment is in conditions where the relative humidity and temperature fluctuate, it will expand and contract. The parchment moving causes strain on the paint layer, resulting in it cracking. The paint layer does not penetrate through the parchment but sits on its surface. Once it has cracked, it is in danger of becoming loose and eventually becoming detached from the parchment. To stop this, loose paint needs to be glued back to the parchment.

I carefully looked at each piece. Areas which showed that the paint was cracking were examined under a microscope. I guided a toothpick over the cracked areas. If the cracked paint moved then it would need to be re-adhered back to the surface.

Section of PRO 30/25/104/7 magnified 51.3x

The right adhesive

Due to potential problems certain pigments displayed, choosing the right adhesive was important. The majority of the consolidation used adhesive called isinglass. Klucel G in ethanol was used in areas where certain pigments were sensitive.

Isinglass is made from the swim bladders of fish which are processed and dried. As well being commonly used in parchment conservation, isinglass is used in the British brewing industry to accelerate the fining, or clarification, of beer; it was also used in confectionery and jelly before the rise of gelatine, and as a preservative for eggs during the Second World War.

To prepare the isinglass for consolidation, I soaked dried pieces of isinglass overnight in distilled water. I then heated this in a double boiler until it was a clear liquid and filtered the liquid to remove any sediment. Once these stages were complete, I was able to use the isinglass. Isinglass is a very sticky adhesive (even at low percentages) which dries with a clear film. I used a 1% solution as this does not cause changes in the paint layer or gold leaf’s appearance.

Lead and copper pigments

Colours such as red, white and green during this period were most likely to contain lead and copper. This could cause problems when choosing a suitable adhesive, as moisture could cause these pigments to corrode. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was used to analyse to see if any of the pigments contained either copper or lead. XRF is a non-destructive analytical technique used to determine the elemental composition of materials and was tested on the pieces being treated. The greens contained copper, while the whites and reds contained lead.

Green pigment in PRO 30/25/104/8 magnified 48x

Isinglass is not a suitable adhesive in these circumstances so I used Klucel G in ethanol at 1% for those areas of the Commissioni. Klucel G is a cellulose ether and is extremely flexible, drying with a clear film.

Consolidating the pieces

To re-adhere the paint layer, I used a very fine paint brush – a 00000 brush! While looking down a microscope I applied a small bead of adhesive to the edges and back of the loose pigment. Once dry the pigment is held in place. I did this on all the pieces where pigment was flaking.

Conclusion

Ruth and Lucy: The documents, protected from light over their centuries by their bindings and conserved with great care, remain as bright and beautiful as they were in the sixteenth century. They were greatly appreciated by attendees at the study day and we hope to display them temporarily in the Keeper’s Gallery at Kew later this year.