Chris Heather writes: Over the past two years, The National Archives has been cataloguing a selection of railway accident registers from 15 different railway companies from the era before nationalisation, making these records searchable via Discovery, our catalogue. The results of the data gathering exercise will also be added to the Railway Work, Life and Death database run by Portsmouth University, and hosted on a dedicated website which will include a whole host of additional background information on railway accidents.

So far we have added nearly 20,000 of these incidents to our National Archives catalogue, but we have many thousands more to add. Helping us with this work is a group of dedicated volunteers, one of whom – Andrew Munro – stumbled across an important discovery, which he describes in the following blog entry.

For the last two years I have been working on the Railway Accident Registers Project at The National Archives in Kew, cataloguing the accidents that occurred on the Barry Railway in Glamorgan, Wales, during the period of 1917 to 1921, and on the Midland Railway from 1902 to 1905. As you would expect, the vast majority of these accidents involved employees such as labourers, gangers, locomotive drivers, cleaners and guards.

The registers record a wide range of different injuries, from bruised fingers and sprained ankles to the most severe paralysis, and the deaths of workers run over by trains. As well as employees I have regularly encountered incidences of trespassers being run over and killed by trains, which appear to be cases of suicide. However, I had never encountered the accidental death of a passenger until recently, and I was somewhat taken aback when I came across my first example.

The accident

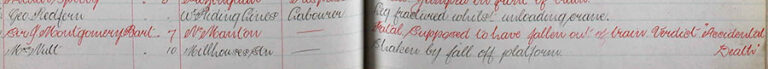

During my cataloguing of the Midland Railway Accident Register covering year 1902 (RAIL 491/1061), on page 68 I came across a most fascinating discovery: the fatality of the Scottish Baronet, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir James Henry Gordon Graham-Montgomery. On Friday 7 November 1902, the Baronet was on board the train that was travelling down from Edinburgh to St Pancras, London. At around 07:00, there was a tragic accident near Manton station in Lincolnshire. The entry in the Register simply states that the Baronet was: ‘supposed to have fallen out of the train. Verdict – Accidental Death’.

Exactly a week later, The Stamford Mercury newspaper, dated Friday 14 November 1902, gives a very detailed report stating that a ganger (a man in charge of a group of labourers) named Ezra Pratt found the Baronet lying in the six-foot way on the Midland main line about 100 yards from Seaton Tunnel. His head was badly injured and one of his feet was severed. Life was not then extinct, but he died 10 minutes later. The inquest, which was conducted on Monday 10 October at the local George Inn, produced the following deductions: While the train was in motion, the door had swung open suddenly, causing him to fall out onto the adjoining railway line. He was immediately hit by the approaching 06:25 train.

Who was Lieutenant Colonel Sir James Graham-Montgomery?

Born in 1850, and 52 at the time of his death, he was the son of Sir Graham Graham-Montgomery and Alice Hope Johnstone. He inherited the title of the Baronet Montgomery of Stanhope in June 1901, following the passing of his father, becoming the fourth holder of this title, and acquired Stobo Castle, located within the Scottish borders, in the historic county of Peeblesshire.

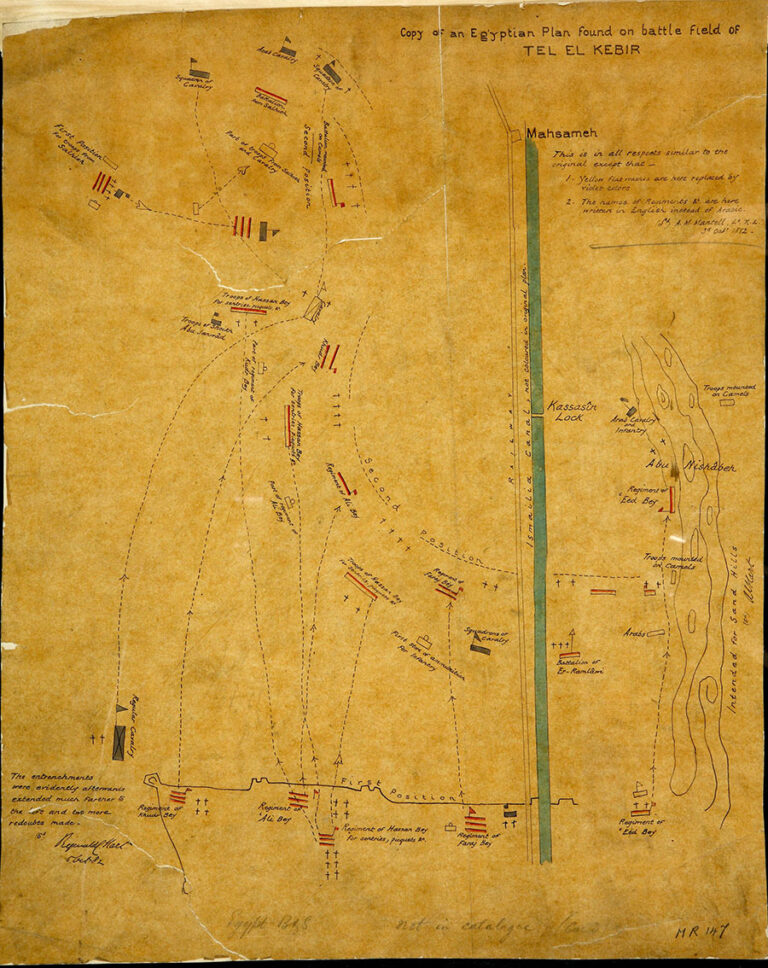

In what was to become a life of great distinction, he was educated at Eton College, and was commissioned into Britain’s oldest continuously serving Army regiment, the Coldstream Guards, in 1869 as a Lieutenant. He served his country in the Anglo-Egyptian War in the year 1882, in which he saw active service in the highly significant and pivotal Battle of Tel El Kebir on 13 September of that year.

In recognition of his gallantry, the then Lieutenant Sir James Graham-Montgomery was awarded the Egypt campaign medal, with the accompanying clasp, as well as the Khedive’s Star medal. In 1889, he retired from the British Army retaining the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He never married, and in later life he served as the Deputy-Lieutenant for Kinross and Peeblesshire.

Suicide?

The inquest into the circumstances of the accident, as reported in contemporary newspapers, arrived at a verdict of ‘Accidental Death’. Crucially, the notion that suicide may have been a motive on the part of the Baronet was dismissed at an early stage owing to the testimony of his brother, and successor to his title. The Stamford Mercury reported that, according to the new and fifth Baronet, he had:

‘never heard him (Sir James Graham-Montgomery) threaten to commit suicide, and there was no reason to believe that this was anything but an accident. He was in a very cheerful frame of mind and was arranging to grant a lease of one of his places in Scotland.’

An open door?

In addition, the possibility that the carriage door of the Baronet’s compartment was inadvertently open was effectively ruled out. Again, the Stamford Mercury reports:

‘The Coroner: “If the carriage-door had been open between Harringworth and Bedford would it have been noticed?” – Witness (Mr Bennett, Midland Railway Inspector): “Yes, (it) would have been noticed at Gretton. The signal-box is on that side and the train would have been stopped. There are seven signal-boxes (on) the six-foot side between Harringworth and Kettering – a distance 13 or 14 miles, and nothing whatever was noticed. If the door had been open (this) would point towards the rear part of the train, and the wind would keep it open. The drivers of two passenger trains which would pass this one did not see anything.” ….. Witness added that it was nearly dark at the time of the incident.’

Soporific confusion?

A third option was mentioned in the obituary published in The Times newspaper on Monday 10 November 1902, in which it states that the Baronet ‘had given his ticket to the guard as he wished to sleep and it is supposed that on awakening suddenly he must have unconsciously opened the door of the compartment he occupied by himself, and have fallen on the line, the 6 o’clock train from Kettering passing shortly afterwards, and severing his foot’.

Company negligence?

A fourth option occurs to me, which is the possibility that the carriage door was defective, a possibility which does not seem to have been considered at all, let alone assessed and evaluated. Considering reports that Sir James Graham-Montgomery was perfectly content with his life and was certainly far from being in a suicidal mindset, one cannot help but wonder whether the carriage door was indeed defective owing to negligence on the part of the Midland Railway Company.

If this was the case, it appears to have escaped the notice of the inquest and the Railway Company. Indeed, I have seen many incidents involving railway workers recorded in the Accident Registers which could be interpreted as due to the negligent practices of the company. Unfortunately, we will never know the absolute truth and all the facts in this case.

Burial

Following the inquest, the body of the Baronet was conveyed up to Oban and was buried in the graveyard of Stobo Kirk, a medieval church with origins that can be traced as far back as the sixth century. The church and graveyard are situated just six miles south-west of the town of Peebles in the historic county of Peeblesshire in the Scottish Borders, where visitors can still see the family gravestone.

For me it has been a very thought-provoking process to discover, while undertaking my cataloguing work, the untimely passing of a man who had accomplished many notable achievements during his all too short life. It is perhaps ironic that Sir James Graham-Montgomery survived the horrendous conditions and hardships of the Egyptian battlefield at Tel El Kebir in 1882, only to be killed on a peaceful railway line in rural England. It also brings to mind the death of William Huskisson (President of the Board of Trade), who was the first person to be killed on the passenger railways in 1830, and who died from injuries received in a very similar accident.

Unexpected discoveries such as this one are prime examples of why I have found it so rewarding to work on the Railway Accident Registers Project at The National Archives.

Why was the body taken to Oban if he was buried in Pebblesshire?

This is a fine exemplar of the outstanding work undertaken by the Staff & Volunteers of the TNA that bring the past to life. Thank you!

The reporter states the train was heading DOWN to St Pancras. In fact he was heading UP to St Pancras.

All trains, no matter where the location in England, Scotland or Wales head UP to London.

It may seem strange that a train heading south is traveling down to London but believe me, it was heading UP.

Even trains travelling from Edinburg to Inverness are travelling down, even though heading north. I kid you not.

Former railwayman of thirty years.

R W Hind.

“Following the inquest, the body of the Baronet was conveyed up to Oban and was buried in the graveyard of Stobo Kirk, a medieval church with origins that can be traced as far back as the sixth century. The church and graveyard are situated just six miles south-west of the town of Peebles in the historic county of Peeblesshire in the Scottish Borders, where visitors can still see the family gravestone.”

Oban? Oban is not at all near to Peebles. More explanation required 🙂

This is fascinating reading…..I have something similar in that a great uncle fell out of a train and was run over by the wheels(!). This was at Lochmaben, Scotland in 1881. He was only 21 and his father was Inspector of the Line !! I can’t find any record of it anywhere and I think it was hushed up!!

My maternal grandfather was killed on the Midland Railway at Stockingford Station near Nuneaton where he was a guard on the local “paddy” train which took miners to work at a pit nearby. He slipped on an icy rail to step away from an express coming through and his own train reversed over him. I have all his inquest papers with statements from his work colleagues all of whom were happy that it wasn’t suicide. This was January 1924. I also have inquest papers for the father of an uncle by marriage who was also killed on the Midland Railway near Coventry in the early 1920s. His papers are not as detailed.

Fascinating, thank you so much, I will check out the Railway Accident Project in future, my 3x great-grandfather was killed under the wheels of a train on 18 February 1860 at Fenny Bridges in Devon. He was walking and working on the line and climbed the ballast, when the drain went by he slipped and went head first under the wheels – the driver said it was a bad day as they had killed donkey that day which had wandered onto the line! I have the newspaper report of the accident and will now see what is available at the National Archives – when I can! Thank you.

Very interesting account, and leaves me with many unanswered questions not likely to be ever answered !

If he never married, why is Margaret Scott mentioned on the gravestone?

Why was the body conveyed to Oban (100 miles NW of Glasgow) if he was to be buried at Stobo?

Interesting story. Why was the body conveyed to Oban and then buried in Stobo Kirk, two locations separated by over a hundred miles?

There was no doubt as to the cause of Huskisson’s death, and it was in no way from “a very similar accident”. Huskisson was attempting to get into – or be helped into – a carriage when he was hit by another train. You appear not to have considered that Sir James Graham-Montgomery could have been murdered, by someone opening the carriage door and pushing him out.

I have been researching a ghost town (Glenbow) in Alberta, Canada and found newspaper accounts of a woman who had been travelling with her sister on the Canadian Pacific Railway express train from Vancouver, British Columbia to Winnipeg, Manitoba. The train passed through Glenbow at 10:15 PM. The woman’s sister reported her missing sometime after that, but she was not found until the next morning. Newspapers reported, “Lady Somnambulist Meets With Serious Accident on Train — Is Much Injured.” For the full story see my blog — A Quill in the Digital Age, October entry: .

Is it possible Sir James Graham-Montgomery sleepwalked off the train?

Am I able to quote parts of the document in a local history club newsletter? With full acknowledgement of course.

The incident will be of local interest in Northampton as it is close to the Gretton and Kettering main line.

An interesting and well researched account.

I am reminded of an incident on a train in the early 1960’s when I was in the Boy Scouts. Returning from a summer camp in the Lake District, it was a long and tedious journey heading back south. The carriages at that time has compartments and a single corridor; outside doors being at each end. One of our scouts went to the rear door to pass the time looking at the view. He lowered the window (controlled by a leather strap) and then leaned out to catch the breeze and the view. He had crossed his arms on the window sill and was resting on them. Suddenly, without warning the door swung open to about 90 deg and he was left dangling. Fortunately his weight was fairly balanced, 1/2 in & 1/2 out of the window and he manged to hang on. By shear chance the ticket collector came into the carriage, saw what was happening and managed to pull my friend in and close the door. BR staff were not known for their jovality and there followed several choice words directed at the victim.

The door was definately shut before he leaned out (otherwise he would have noticed a rattle, and it was firmly shut afterwards. With his arms crossed there is no way he could have opened it himself, unless somehow a moved leg had precipitated the event, but unlikely since the handles had to be twisted to open. Clearly it is unadvisable to lean out of windows on trains!

A very intteresting account of the tragic accident. My son works for Network Rail and carries out maintenance on the line near Watford and I have forwarded this email to him which I an sure he will also find intewresting. Thank you for bringing this Archive to my attention.

The GWR had some coach door locks which required someone to positively turn the handle outside – they were not slam-locking. Either a passenger lowered the window to do that (and to turn it to exit), or a member of station platform staff did. In the 1950’s a train could have carriages with both these and slam-locking doors. Although the handle of the first sort would be un-turned, a door slammed could remain shut unless pushed from the inside. I as a child age about 5 did just that and fell onto an adjacent track, fortunately without injury. The door lock was not defective. This was at lunch time, so in good daylight. Did the Midland have similar door handles?

Interesting..

..and alternate history if Vane-Tempest had not died at Abermule and left money to Winston Churchill..

Why was the body conveyed to Oban, which must be quite some distance from Peebles?

I am wondering why his body was conveyed to Oban which is about 147 miles from Stobo near Pebbles. Is there a reason or is it an error?

I think you have got the train travelling in the wrong direction. The ‘down’ Edinburgh/St. Pancras train started from St. Pancras.

All of the signal boxes mentioned are to the south of Seaton tunnel which again suggests that the train was north-bound.

Key evidence would have been whether the window had been found open or not but no doubt in those days the train would stayed in service for some time after the event and might well have never been examined.

He fell from the train, the door would have been held open by wind pressure, it was closed, therefore someone closed it. You don’t exactly need to be Herculese Clouseau to work out that as he was pushed out by someone who then closed the door it was therefore murder or assisted suicide at the very least do you?

A few things to consider. Was it dark at 7am on that November morning? Had the train stopped at signals, or slowed down significantly, giving the impression of an approaching station (though preumably this was an express with few scheduled stops)? Could the door be opened from the inside, or did it require the window to be lowered to reach out for the handle? Was the offending carriage identified later so that its doors could be checked? Presumably he was travelling with luggage, so it should have been easily identified. Also to be considered is the fact that there would have been considerable reluctance for an inquest to return a verdict of suicide which was a criminal offence at that time, and could lead to refusal for burial in consecrated ground.

Another unexplained accident took place in rather similar circumstances took place on 11 July 1946 at Cuckfield Sussex. The lady involved was later identified as Mrs Mary Bardwell nee Campbell. If any more details can be provided from the archives I would be most grateful

I think the incident was at Manton, Rutland, on the Midland Railway line between Saxby and Kettering. Manton, Lincolnshire would be a long way off-route, not to mention off-railway.

Pointless investigation probably only prompted because this person had the useless, archaic title “Sir”.

Who pays for investigations into useless pieces of information like this!?

The thought that first crossed my mind is how would the door have closed again – unless some-one closed it after pushing him out so as not to raise suspicion. Was there any mention of personal belongings being missing?

By coincidence I came across a case yesterday of someone who fell out of a train in the World War II blackout. The train had stopped at a signal, but the passenger thought it was the station. It would be dark at 7p.m. when the above accident happened, and maybe the Baronet was confused as he woke up.

What an odd and interesting incident! It does seem surprising that the coroner didn’t even consider whether the carriage door was faulty…?

One note: I found the dates confusing. According to the article, the death occurred ‘On Friday 7 November 1902’, with a detailed report of the finding of the body published a week later, on 14 November. However, ‘The inquest…. was conducted on Monday 10 October[no year specified] at the local George Inn.’ Did the inquest really not take place until 11 months later? Or is there a typo in the date of the inquest? Monday 10 November would seem much more usual.

Very interesting. As a similar accident had also occurred. There is a good possibility that there was a problem with the doors.

Thank you for bringing this to the site. I look forward to reading more of your findings.

Thanks for the story and the insights. It is always amazing to me the stories that can be found in old indices, registers and papers that people think are worthless. I’m trying to track down the death of my GG Grandfather and hope one day his accident will be catalogued.

Interesting history…

It states above that he never married, yet the gravestone claims he had a wife, Margaret, also buried there… ???

Interesting article. One thing that puzzles me is why his body was conveyed to Oban (west coast of Argyll) before burial at Stobo in the Scottish Borders.

Why would his body be sent to Oban on the west coast of Scotland? Surely it would have been sensible to send the body to Edinburgh for conveyance on to Peebles.

You would suppose that at some time the open door would have been seen and closed. Who did this etc?

The gravestone says… ‘and his wife Margaret Scott of Killearn’. At the end of a paragraph in the report above it says ‘He never married…’ . What?!

What a fascinating and extremely interesting article. I also loved reading the comments left by others. I agree that it may well have been a faulty door. It brought to mind the old British Rail trains where the carriages had those hard to pull back locks to open … in the end you just pushed the window down and turned the handle to get the wretched door open. You had to slam them hard to shut them, otherwise they would appear shut, but their rattling told you otherwise.

Anyway, what a great article. Thank you. I am of to investigate further.

I would like to find out what happened to my Great Grandfather in 1874 when he fell off a train and died, but am not sure if the records go back that far. In the book “How Green was My Valley” it is said to have been Christmas Evans, but it wasn’t.

As a railway fan, I know about trains going ‘up’ to London, and ‘down’ from London, but I never understood how it worked on a cross-country line, say, Birmingham to Bristol.

Shame Sherlock Holmes wasn’t on the train – he seems to have been on so many!

It is possible the door would not have able to be closed if the door opened into the wind if you see what I mean,it would have been extremely difficult to close the door if travelling at speed,it would have been pinned back against the carriage body.As a retired railwayman of many years standing the rule book is effectively a response of many accidents over the years and the lessons learned to make railway travel safer.Unfortunately incidents of persons falling from trains were probably more common than you would think.Not a lot would have able to be done with this sort of accident.I remember that when the HSTs were introduced in 1976 some commented on the fact that they had slam doors,and as you can imagine there were some fatalities as a consequence.Until eventually locks were fitted.Although I cannot recall any from memory I do remember the Southern Region experimenting on converting one electric unit to have individual locks on each doors in the 1990s because it was becoming such a problem.

I doubt whether the signalman or any other casual observer would have spotted an open train door at 07.00 in November.

To Chris Parker. No one pays. Andrew Munro is a volunteer.

Re the gravestone it lists several members of the family. The Margaret mentioned died in 1806 and was the widow of Sir James who died in 1803.

Indeed why Oban, surely the body would have been taken to Glasgow or Edinburgh?

Accidents of this type have happened in my country, New Zealand, at the time about which you write.Several of them happened because the door of the on-board toilet was very close to the external door of the carriage. Tired or intoxicated passengers were very much at risk. More recently, in the 1960s, a student failed to turn up on the train home from university. His family was panic stricken for several days, as he appeared to have just disappeared from the train. It was a great relief when he was found on the tracks in a dazed condition. He had fallen off the train and wandered along the line for many days.

I am an amateur genealogist & instances such as this are frustratingly common. All the possibilities others have raised are feasible, to which I would add that the brother’s testimony could be suspect; suicide carried legal as well as social consequences, both of which the family would have wanted to avoid.

As regards falling out of trains, in my research into the life of the antiquarian, Rev. Elias Owen, I came across the following article in the Rhyl Advertiser of 27 July 1878:

“FALL FROM A TRAIN.

On Wednesday night, Mrs. Owen, the wife of the Rev. Elias Owen, St. Asaph, diocesan inspector of schools, was returning from Rhyl with her children. Whilst the train was going at full speed, between Trefnant and Denbigh, the door flew open, carrying one of the children with it. The occupants were greatly alarmed, believing the child killed. On arrival at Denbigh the engine was sent back, a gentleman accompanying the driver to point out the place where the child dropped. To their astonishment they met the child running along the side of the line, making her way to Denbigh. Luckily she had dropped on a part of the line where the grass was very thick, and escaped with a few bruises.”

In answer to the questions of Sir James never marrying and the gravestone mentioning “and his wife Margaret”, it’s the family gravestone and you can see the names mentioned of James and his wife Margaret are just the first on the stone and ancestors of the tragic sir James in question is second from the bottom named on the stone and died in November whereas the first Sir James on the stone died in the month of April

Fascinating story and comments

Some interesting inconsistencies in this saga from the destination of the corpse, the reports that the signalmen should have seen the door and the date of the inquest. I would have thought though that even if signalmen missed the door it would surely have been noticed at a major station (Kettering and Wellingborough) even at dawn, also would an open door not have sustained damage from striking line-side structures etc. between Seaton and Bedford that would have been subsequently noticed and reported on.

According to the ganger, Ezra Pratt, he discovered the injured victim 100 yards from Seaton Tunnel [which end of it is not clarified], still alive at the time, dying ten minutes later. Seaton tunnel and the track either side is in Seaton parish that in 1902 would have been in Rutland , some distance from Manton, Rutland.

Turning to the location and date of the inquest in The George Public House. The only pub in Seaton was the George and Dragon but there is a very old pub named The George in Stamford that is of course in Lincolnshire. The law at that time was that inquests must take place in the Coroners District where death was certified, also inquests could take place in public houses. Inquests took place with what we would describe with undue haste to enable the corpse to be buried [no refrigerated mortuaries then!].

If the body was taken to Stamford, the nearest town of any size, and death was certified by the first available doctor there then the inquest would have taken place in Lincolnshire. As recently as the early 1970’s in one Northamptonshire market town the list of jurors for coroners inquests consisted of no more then eleven or twelve names, the same people being called all the time – I will say no more except to say from my perspective inquests could be perfunctory even then, goodness knows what they were like in 1902! I seem to recollect reading that in those days it was practice to have the corpse present for the inquest to view, I do wonder how that went with food safety being in the bar of a pub!

Looking at newspaper reports etc. the inquest did take place on the 10th November 1902.

Regarding Margaret Scott, she died in 1806, the wife of the late Sir James Montgomery who dies in 1803 – their names are at the top of the headstone, our man is very close to the bottom. Possibly this stone marks a family mausoleum.

It appears to me that with the speed of communications as there would have been in 1902 together with the probable involvement of two county police forces – Rutland County Constabulary and Lincolnshire Constabulary and the doubtful involvement of The Midland Railway’s own police. The Midland did not organise its own police force into anything recognisable by today’s standards until 1910, before then railway police forces would not have been exactly efficient.

http://www.btp.police.uk/about_us/our_history/detailed_history/detailed_history_2.aspx

All of these factors would have resulted in a lack of ownership of the case and a poor investigation by the police by today’s standards to ensure that no crime had been committed.

All in all this probably was not a suspicious death, just one with many unanswered questions.

The situation would be much clearer though if there were details of the railway’s enquiry into the incident. When was the door found open, were his personal belongings intact etc.?

Why was this train routed via Seaton and not Market Harborough?

An interesting saga!

This is clearly a family grave marker with earlier Montgomery forebears mentioned. Margaret might well be his great great grandmother!

In reply to some of the above comments, Chris Heather (Transport Records Specialist, TNA) writes:

It is gratifying that so many people have commented on this excellent blog entry by Volunteer Andrew Munro. I hope the following will help to answer some of the questions raised.

Wife: both obituaries in The Times (10 November 1902) and The Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury (14 November 1902) state that he was unmarried. The wife named Margaret Scott, mentioned on the gravestone, is that of a different relative – also named Sir James Montgomery, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer who died in 1803. The ‘gravestone’ is actually a memorial for several members of the same family many of whom has similar names and titles.

Location of death: the obituary in The Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury (14 November 1902) states that the Baronet was found about 100 yards from Seaton Tunnel (Rutland), the train which was likely to have hit him having just passed Harringworth (Northamptonshire).

Direction of the train: the obituary in The Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury (14 November 1902) states that the train left Edinburgh at 10pm and was due to arrive at St. Pancras at 8.17 the following morning, as attested to by the Guard of the train James Liddle who actually spoke to the Baronet at Carlisle and saw him apparently asleep at Sheffield.

Theft: in reply to suggestions that the Baronet may have been the victim of theft by an assailant, when searching the body a sum of money (£9 0s 8d), a pipe, tobacco, letters, a cigar case, 16 keys and a silver match box were found in his pockets. I would therefore think it unlikely that was attacked with this motive.

Oban: It is unclear why the body was taken to Oban, although the obituary in the Stamford Mercury clearly states: ‘Later in the day the remains of the deceased Baronet were conveyed to Oban by Special Train, under the supervision of Messrs. Oates and Musson, of Stamford.’ This may have been an editorial error by the newspaper, or perhaps Oban was the final destination for the train, with the body leaving the train closer to Stobo, Peebleshire.

There has always been confusion about the Midland Railway’s use of the words ‘up’ and ‘down’ in describing direction of travel. When the Midland Railway was created, Derby was the centre of their world, and trains going there were going ‘up’. Opening their line to London came later, but that was away from Derby and going there remained ‘down’ in their internal communications. I don’t know when they ‘fell into line’ to have London as ‘up’, but presumably that would have been enacted at the Grouping, 1922/23, if not earlier.

An excellent piece by the volunteer researcher, thank you. It shows just how much detail there is to be unearthed.

I have been researching a similar incident from May 1902.

Marianne Stopford Claremont (previously Mcneill- Hamilton and Nee Ewing) , also a member of the Scottish aristocracy, was found deceased by railway line in London. The report in the Evening Telegraph (5th May) suggested she was in good health had never considered suicide and had an adequate independent outcome. The inquest suggested accidental death having fallen from a train after waking up thinking she was at the station.

Looking at her life however she had suffered loss and trauma in her childhood, she was born in Alabama, daughter of a Scottish slave trader, an only child, moving at the start of the civil war in 1861 aged 13 to Glasgow, away from her parents, who both died shortly after. She married aged 22, lost her first husband in early married life, the 2 youngest of her 3 sons were criminals from a young age despite their privileged background, one going on to spend most of his adult life in prison. Her oldest son Captain Henry Mcneill Hamilton who lived in the McNeill Hamilton family house in Scotland also had a questionable reputation at the time of her death. She remarried Col George Stopford Claremont(from Worcester) in 1887 but he died 4 years later in 1891, leaving considerable debt. In 1892 she had an admission to Gartnaval Royal Asylum. By 1896 she is reported as in debt (“A Malvern Lady’s Failure”) and was berated in the press for spending but having had no occupation. She went on to sell all her assets and in 1901, and at the time of her death, she was living in a hotel in London – Her £600 pa income came from her 1st Husband. She was hardly on the breadline but her multiple losses and her reputation were probably issues for her mental health and suicide was at least a significant possibility . I wonder if inquests err on the side of accidental death to protect the family feelings and reputation.

Have you any information on earlier Midland railway accidents please?

According to a note in The Oxford Companion to Railway History edited by professor Jack Simmons There is a report of a midland railway Accident in Hereford in 1889 involving a coach movement. it is stated in the accident report that the coach had originated in London giving evidence the the MR ran a through coach at least as far Hereford but more likely Brecon and even to Swansea (St Thomas station) The online national archive has no other detail on this

The GWR ran from London to Swansea

The LNWR also ran from London to Swansea via Stafford

Very interesting and intriguing. If we accept that the Baronet had taken a drink, the reference to him not wishing to be disturbed and seeking to rest. I wondered if the train was of corridor stock and fitted with toilets? If not did he awake, needed to well you know, open the door to relieve himself and overbalanced, fell from the train or in the struggle to close the door after he was done, against the rush of the wind overreached and fell?

A question posed re direction of trains. On the midland railway the up line was always towards derby as derby was the hq of the midland railway. This is still the case on todays railway .

If, as seems to be the case, the grave marker is actually a memorial stone for the family, it may be a good genealogical source, but not necessarily prove that our man was buried there. Has the burial been found in the registers, or is it just assumed from the stone?

I’m not a rail enthusiast and don’t understand how the railways were structured during this period beyond the plethora of regional companies that existed. Can anyone tell me, please, if this accident occurred on the Flying Scotsman? Many thanks.

The body was taken to Stobo Castle, his residence, then to Stobo churchyard.