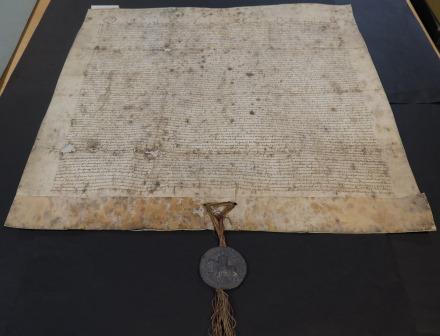

Seal (front side) of Edward of Woodstock, 1365 (catalogue reference: E 39/26)

In 1367 an Anglo-Gascon army led by Prince Edward of Woodstock, also known as the Black Prince, shattered a Franco-Castilian force near the town of Najera in Spain. This victory highlights a forgotten Iberian dimension to the Hundred Years’ War, and provides another example of Prince Edward’s reputation as an astute military commander.

Anglo-French rivalry had irresistibly spread to the Iberian Peninsula during the 1360s. The two kingdoms were tenuously at peace but political rivalry continued unabated, especially in the Iberian kingdom of Castile, which was divided by civil war. Castile became a new battleground for English and French ambitions, with both sides backing rival contenders to secure the friendship and resources of the largest of the Christian kingdoms in Iberia.

Discovering how or indeed whether our documents shed any light on this posed a genuine challenge. This is especially true because our medieval record collections tend to be administrative in nature, and not the colourful narratives of literary sources.

Nevertheless one finds that relevant material is not only to be found but in fact enriches our understanding of the campaign, the preparations made, the soldiers who served and England ‘s commitment to the alliance it had with the incumbent ruler of Castile Peter I.

The Treaty of Libourne, September 1366

In 1366 England’s Castilian ally was overthrown by his half-brother Henry, count of Trastamara. Peter fled to the court of Prince Edward in Gascony to seek refuge and succour.

Persuaded by the obligations to Peter under the 1362 Anglo-Castilian treaty, Prince Edward agreed to raise an army to restore him to his throne. The treaty of Libourne confirmed Peter’s commitments to reimbursing his English allies financially and through territorial concessions. Charles II, ruler of the tiny kingdom of Navarre, sandwiched between Gascony and Castile, also secured promises of compensation for allowing the invading army to pass through his territory.

Treaty of Libourne between Peter I of Castile and Leon, Charles II of Navarre and Edward Duke of Aquitaine and Prince of Wales, 23 September 1366 (Catalogue reference: E 30/230)

The seriousness with which the English Plantagenet dynasty took its obligations to the reaffirmed alliance is demonstrated in an order dated 6 December 1366 in the Close Rolls. The King ordered the mayor of Bristol to de-arrest a Spanish ship, recently arrested in the port, as recompense for an English merchant ship of Bristol recently seized by subjects of the Castilian usurper Henry and deliver it to its master. The reason for this royal order is explicitly stated as being because:

‘…an alliance has been made between the king and Peter the true king of Castell [Castile] for them and their subjects, and the king would not that this alliance be weakened by reason of faults committed by the said Henry the pretended king thereof and by his adherents.’ (Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, Volume 12, p. 255)

Military preparations

Evidence of the military preparations can also be found, albeit sparser than for other military campaigns to the continent during this period. This was primarily because the majority of soldiers and equipment for the expedition were raised and supplied in Gascony rather than from England.

However, the Gascon rolls (C 61/79) provide evidence of military preparations and of increasing numbers of soldiers travelling to Gascony in the summer and autumn of 1366. These rolls document certain administrative business concerning the English-held duchy of Aquitaine (Gascony) including soldiers requesting letters of protection of their property or appointing attorneys to represent them while on service there.

Several combatants served in a retinue led by the Black Prince’s younger brother John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, including Walter Urswick. Urswick would become one of the duke’s most loyal and favoured retainers after being knighted on the battlefield of Najera. On 22 November 1367, a grant of £40 yearly was given for his maintenance as a knight and for good service rendered in Spain and elsewhere (Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1367-1370, vol.14, p.78). Walter’s letters of protection were enrolled on 2 November 1366 and four days later he appointed John and Thomas Southron as his attorneys (C 61/79 m.4).

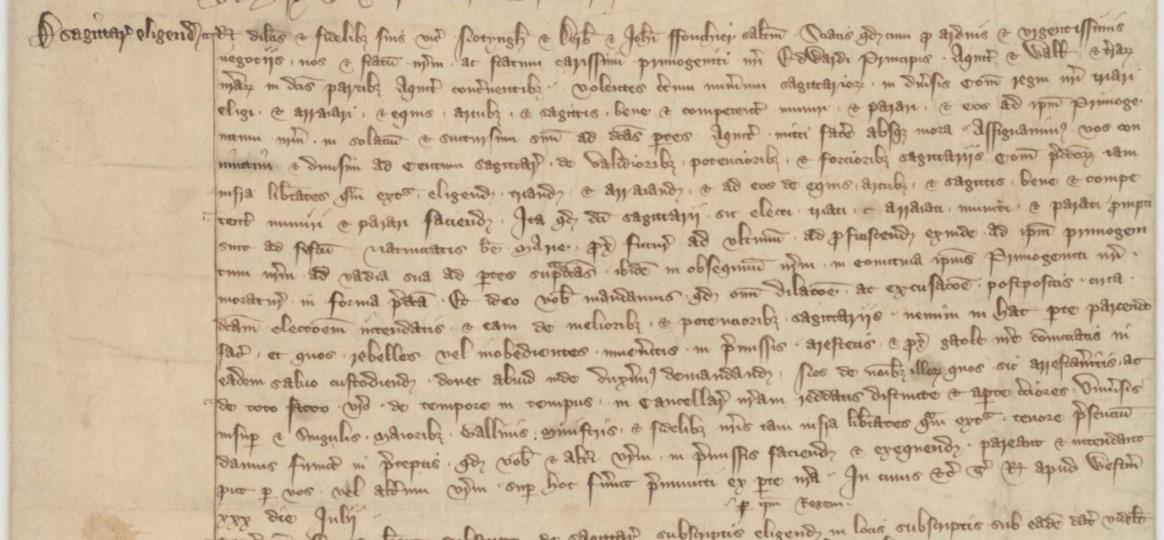

The rolls also confirm that preparations were made for raising forces in England to supplement those being raised in Gascony. On 30 July, sheriffs of counties across England were ordered to raise and equip between 20 and 100 of ‘the healthiest, strongest and bravest’ archers in their respective counties by no later than 8 September for dispatching to Aquitaine. If quotas were met, a total 940 archers were raised for service with Prince Edward (C 61/79 m.10).

Entry assigning the sheriffs of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire and an official John Fouchier to raise and equip 100 archers between them from their counties (Catalogue reference: C 61/79 m.10)

Added to this were a further 350 archers raised in the duke of Lancaster’s own lands to serve with the duke, including orders to Walter Urswick who was constable of the Castle of Richmond, Yorkshire (C 61/79 m.9).

The campaign and battle

The Anglo-Gascon army, numbering approximately 8,000-10,000 men, mustered at Dax. Over the course of January and February 1367, they crossed the high passes and defiles of the Pyrenees mountains and the small kingdom of Navarre.

From early March, the prince’s army was encamped around Vitoria for nearly a month while Henry of Trastamara’s forces had taken up defensive positions to the west, around Zaldiaran castle. With his route south blocked, supplies dwindling and heavy rains hampering morale, the prince retreated. After several days his army reentered Castilian territory further south, marching towards the town of Navarette. With the enemy army, sited on 2 April, situated on the left bank of the Najerilla River and blocking their route westward, Edward, through a successful night march, manoeuvred his forces to the left flank of the enemy’s location.

On 3 April, the vanguard of the Franco-Castilian army attacked the Anglo-Gascon van commanded by the Duke of Lancaster and Sir John Chandos. As the battle intensified, Henry attempted to reinforce his vanguard’s exposed position; successive efforts were hampered by fire from the English bowmen stationed on the flanks of Edward’s army. Henry’s van was routed and his right and left flanking divisions were in disarray. Despite making a final attempt to rally his forces, his troops broke ranks when the Anglo-Gascon army pressed home their attack. Edward had won a glorious victory – now largely forgotten.

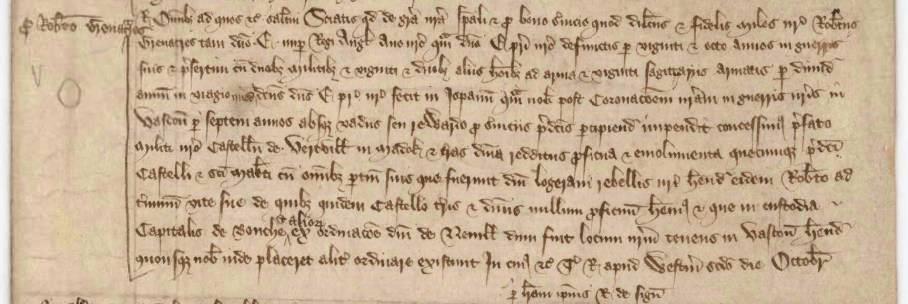

Evidence in the records illustrates that certain combatants were rewarded for their service in Spain, sometimes years later. In 1386, Sir Robert Greenacre was granted the castle of Verteuil in Medoc for 28 years of service in war to the crown, ‘especially’ it says his service ‘with two knights, 22 men-at-arms, and 20 armed archers for half a year in the expedition that E[dward], the king’s father, made into Spain.’

Entry dated 2 October 1386 (catalogue reference: C 61/99 m.7)

Legacy

This military gambit would eventually prove to be a costly failure. Although restored to his throne Peter reneged upon his promises to reimburse Edward and his army, which caused a financial crisis in the duchy and earned the enmity of many of his unpaid Gascon subjects. Moreover the prince’s victory did not secure his ally on the Castilian throne. France eventually succeeded in securing Castilian allegiance two years later when Henry retook the throne and murdered his half brother.

It was not however to be the last time that an English army intervened on Spanish soil to try effect dynastic change. Almost 20 years later, the Duke of Lancaster would return at the head of an English army; this time he was bent on seizing the throne of Castile for himself.

More on this story will be covered in a webinar on John of Gaunt’s bid to be king of Castile.