On the 80th anniversary of Battle of Britain Day, it is important to ask why 15 September 1940 was chosen as the national day of commemoration of British victory in this iconic air campaign.

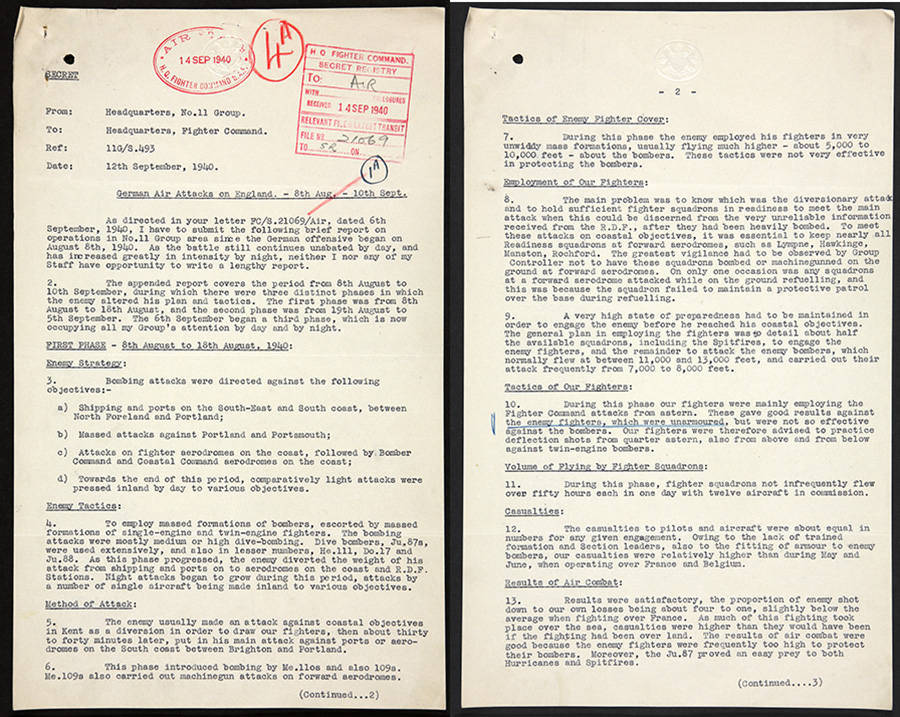

Throughout the course of the air battle which raged in the skies over southern England, Royal Air Force commanders took note of the overall strategy of Germany’s Luftwaffe as their battle groups pressed home their attacks upon various targets on British soil. In a report to RAF Fighter Command headquarters at Bentley Priory, in which he summarised German air activity over Britain in the period of 8 August to 10 September 1940, Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, the commander of the RAF’s No. 11 Group defending the south-east of England during the battle, identified ‘three distinct phases in which the enemy altered his plan and tactics’ (AIR 2/7355).

It would be the alterations in strategy and tactics at the culmination of each phase of the Luftwaffe’s air campaign that would mark the key turning points in the Battle of Britain. Park’s assessment, in the brief seven-page report, outlined the progress of German air attacks, together with the methods employed by Luftwaffe commanders to grind down RAF Fighter Command, erode Britain’s air defences and, ultimately, break the British people’s will to resist.

Air-Vice Marshal Park’s report is held at the National Archives within AIR 2/7355, and can also be found under AIR 16/635. In addition, Park’s instructions to his fighter squadrons following a change in enemy tactics is detailed in a memorandum found in AIR 16/216. Park’s report was drawn up hurriedly after it was requested by Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the commander of RAF Fighter Command, on 6 September. In his introduction, Park takes care to note that, as the air battle ‘continues unabated by day, and has increased greatly in intensity by night, neither I nor any of my staff have opportunity to write a lengthy report’ (AIR 2/7355).

Phase One: 8th August to 18th August 1940

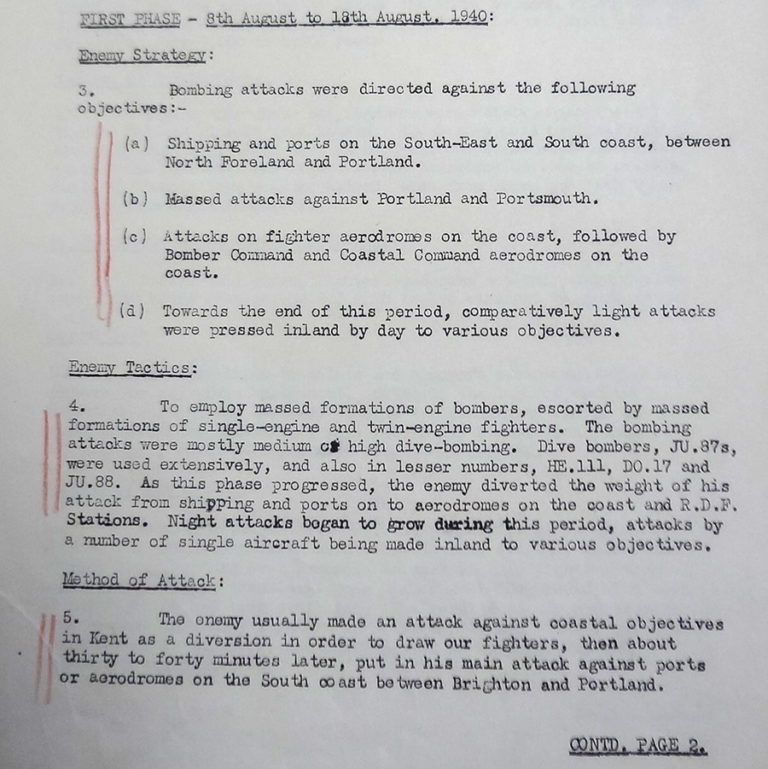

In outlining the first phase, Park observed that enemy strategy involved bombing shipping and port areas along the south and south-east coasts from the very outset, including massed attacks on the Portland and Portsmouth areas. In addition, attacks were mounted on Fighter Command, Bomber Command and Coastal Command aerodromes along the coastline, with lighter attacks occurring further inland toward the close of this phase (AIR 2/7355).

In terms of tactics, the Luftwaffe employed massed formations of bombers, escorted by a screen of both single and twin-engined fighters, namely Messerschmitt ME 109 and ME 110 aircraft. Since bombing attacks often involved medium and high-dive bombing, JU 87 ‘Stuka’ dive-bombers were used extensively. As the phase progressed, the Germans moved away from attacks on shipping and port areas to aerodromes and RDF (Range and Direction Finding) radar stations along the coast. In tandem with this development, night attacks increased throughout this phase, with attacks being made on inland objectives by lone aircraft (AIR 2/7355).

As for the enemy method of attack, Park noted that the Luftwaffe often mounted attacks on coastal objectives in Kent as a diversion in order to draw his fighters away from the primary attack against ports and airfields on the south coast between Portland and Brighton, and both ME 109 and 110 fighters began to engage in bombing and strafing of RAF forward aerodromes.

Park studied Luftwaffe fighter cover, and notably that ‘the enemy employed his fighters in very unwieldy mass formations, usually flying much higher – about 5,000 to 10,000 feet – about the bombers’. He surmised that such tactics were ‘not very effective in protecting the bombers’.

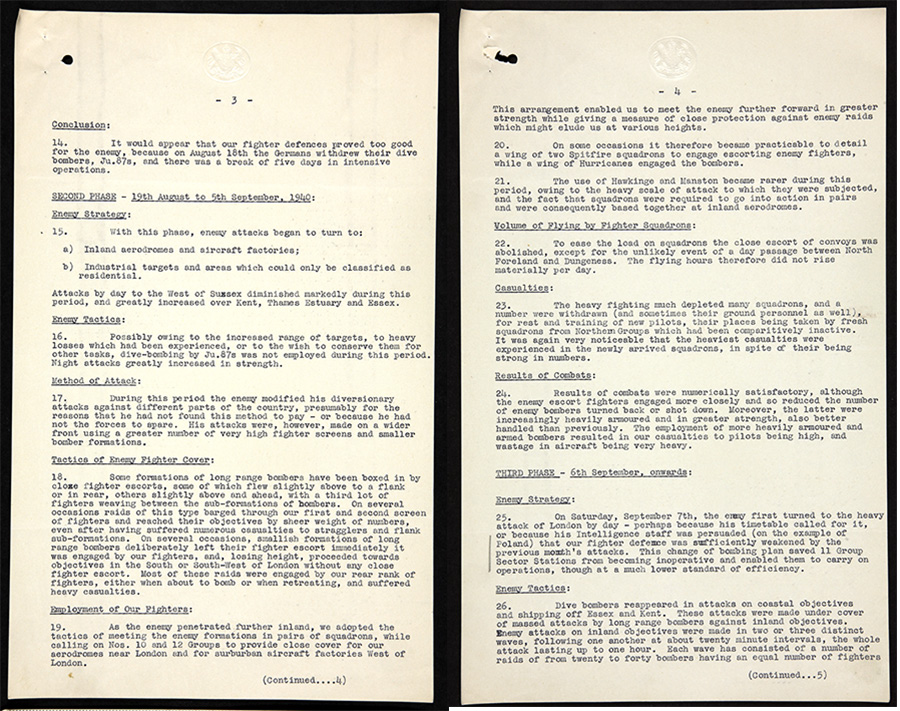

In his summation of this phase, Park deduced that British fighter defences proved ‘too good’ for the enemy, and that the Luftwaffe’s withdrawal of the JU 87 dive-bomber on 18 August, known as the ‘Hardest Day’ because of the intense fighting and high losses suffered on both sides, led to a five-day break in intensive operations (AIR 2/7355).

Phase Two: 19th August to 5th September 1940

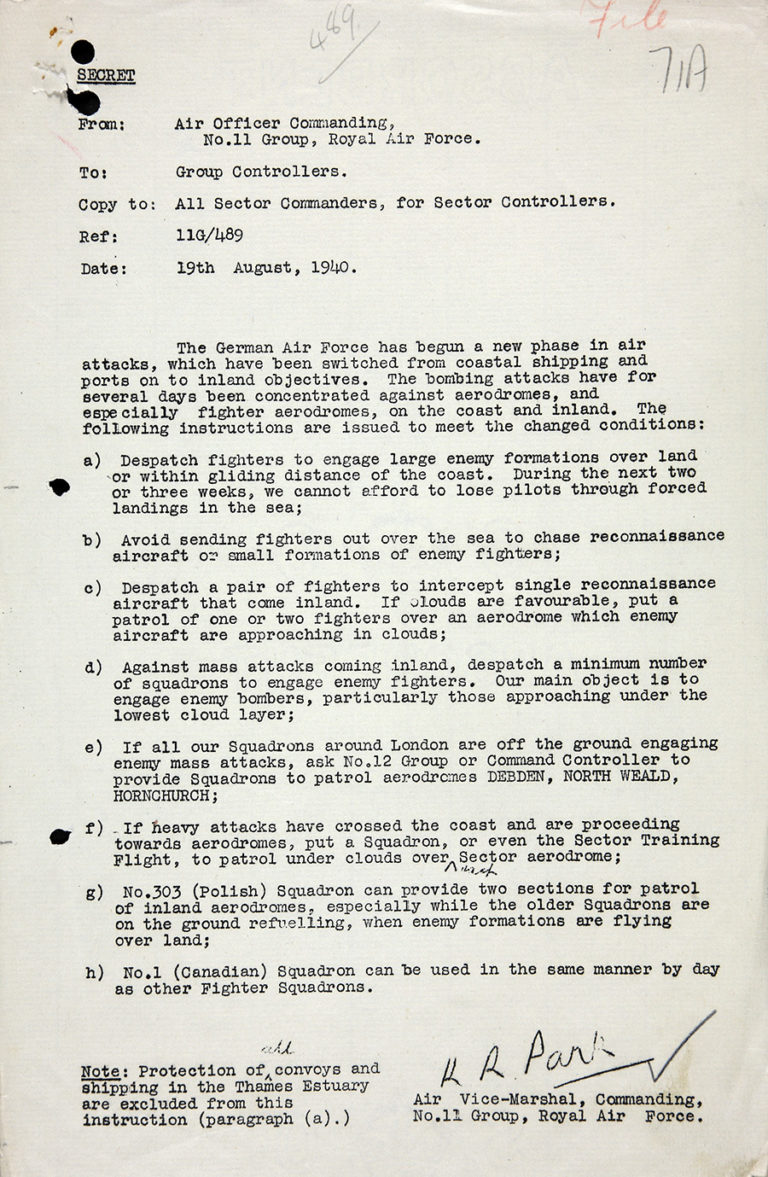

On 19 August, Park issued a directive to all his Group Controllers in the No. 11 Group sector. It informed them that the Luftwaffe were beginning a new phase in air attacks, which switched from coastal shipping and ports to inland objectives, especially fighter aerodromes. Therefore, he delivered instructions to his squadrons to ‘meet the changed conditions’ (AIR 16/216/71A).

In the first instance, he ordered his fighter squadrons to engage ‘large enemy formations over land or within gliding distances of the coast’; Park determined that over the course of the coming weeks, everything needed to be done to prevent his pilots being lost because of forced landings or bailouts in the sea. In particular, he wanted his fighters to avoid going out to sea to chase small groups of homebound fighters or single reconnaissance aircraft. To deal with lone reconnaissance aircraft which came inland, Park ordered that ‘a pair of fighters’ be despatched to intercept these flights (AIR 16/216/71A).

Addressing the more serious question of ‘mass attacks coming inland’, Park instructed that a minimum number of squadrons be scrambled to intercept the fighter escorts; the priority objective for the remainder of his squadrons would be the bombers. If all of No. 11’s squadrons around London were airborne to engage enemy mass attacks, Park advised that No. 12 Group should be requested to cover the RAF stations at Debden, North Weald and Hornchurch. In the event of massed attacks proceeding inland towards aerodromes, Park ordered that a squadron be despatched to patrol over the Sector aerodromes; these bases needed to be protected in order to provide directions to all their satellite aerodromes and airfields (AIR 16/216/71A).

The new foreign Allied squadrons were becoming operational at this time. Among them was the No. 303 (Polish) Squadron, which would soon earn legendary status among all Fighter Command units. For the moment, the Poles were treated as inexperienced and unreliable rookie pilots, and Park considered them useful only for patrolling while the ‘older squadrons’ were on the ground refuelling. He suggested that they should provide a couple of sections to patrol over his inland aerodromes. Meanwhile, a newly operational No. 1 (Canadian) Squadron would be utilised in the same manner as the other squadrons (AIR 16/216/71A).

Throughout phase two, Park identified that the Luftwaffe strategy had been to focus on aerodromes, aircraft factories and other industrial targets, along with the targeting of areas that ‘could only be described as residential’. Attacks by day west of Sussex significantly diminished but increased greatly over Kent, the Thames Estuary and Essex; these were made on a far wider front and using a greater number of ‘very high fighter screens and smaller bomber formations’ (AIR 2/7355).

Some formations of long-range bombers, particularly Heinkel HE 111 and Dornier DO 17 bombers, were boxed in by close fighter escorts. According to Park, on several occasions these Luftwaffe formations effectively rammed their way through the first and second screens of RAF fighters on their way to strike inland targets, only to be picked off at the flanks, or on the return homeward when deprived of their fighter escorts.

As the Luftwaffe penetrated further inland, enemy formation was met by pairs of squadrons further forward while No. 10 and No. 12 Groups provided cover for No. 11 Group aerodromes. Park would also adopt the novel tactic of despatching two squadrons of Spitfires to intercept the enemy fighter screen, while an entire Wing of Hurricane fighters would be allocated towards taking on the bombers (AIR 2/7355).

Phase Three: 6th September onwards (to 15th September 1940)

The third phase brought about a significant departure from the previous two phases. However, this came not a moment too soon, for No. 11 Group. Park’s squadrons had sustained very high losses in terms of pilots, along with a very heavy wastage of aircraft, and many of his frontline squadrons became so depleted that these had to be withdrawn, only to be replaced by relatively inexperienced units from the north which immediately sustained heavy casualties upon being thrown into battle. Park would, therefore, record the opening of this new phase with a palpable sense of relief (AIR 2/7355):

‘On Saturday, September 7th, the enemy first turned to the heavy attack of London by day – perhaps because his timetable called for it, or because his Intelligence Staff were persuaded (on the example of Poland) that our fighter defence was sufficiently weakened by the previous month’s attacks. This change of bombing plan saved No. 11 Group Sector Stations from becoming inoperative and enabled them to carry on operations, though at a much lower standard of efficiency’ (AIR 2/7355).

According to Park, the German attack of 7 September ‘was pressed home by the weight and numbers of successive waves of bombers at short intervals, mainly with fighter escort, all directed at the London area, and in particular at the Docks’. During the 9th and 11th September, the Luftwaffe again struck following the same method of attack when the sky was sufficiently clear of clouds. Southampton was simultaneously attacked on the 11th, with up to 60 enemy bombers. However, Park observed that greater damage was inflicted by night raids, ‘in which all pretence of attacking military targets has been abandoned and consists mainly of “browning” the huge London target’ (AIR 2/7355).

On 15 September 1940, two colossal formations of German bombers and escort fighters flew inland to attack London. It was the final attempt by Luftwaffe commanders to try to break British defenses and public morale; Hitler was now threatening to abandon the campaign, and Göring’s lieutenants were desperate not to fail. When the attacks massed over Cape Gris Nez, Park responded by deploying every available fighter in No. 11 Group. Ultimately, the attacks failed to achieve any significant result, and 60 German aircraft were lost for the cost of just 26 RAF fighters. This action proved to be the climax of the Battle of Britain[ref]Williamson Murray, Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe, 1933–1945 (Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, 2002), p. 52.[/ref].

Two days later, Hitler would postpone preparations for Operation Sealion, the invasion of Britain. Due to the mounting losses of airmen, aircraft and the lack of adequate replacements, the Luftwaffe abandoned daylight raids and continued with nighttime bombing. It is due to this final and decisive turning point in the Battle of Britain that 15 September 1940 is celebrated in the United Kingdom, and throughout the world, as Battle of Britain Day.

The Battle of Britain in the period after Dunkirk in August 1940 and new word in the English language

“THE BLITZ ” and the true grit of all who had to defend our homeland both military and our parents and grandparents had to live through the destruction of our homeland .

The summary of how the Royal Air Force managed to adjust the balance of air power to change the course of the WW2 and to force the German High Command ” to withdraw from their plans called “Operation Sealion ” to defeat the British People . These 7 pages are typical of why we are British keep it simple and to the point . In his conclusion AVM Park statement is the truth reflection of the spirit of how to-day these words have real meaning “NEVER IN THE FIELD OF HUMAN CONFIICT WAS SO MUCH OWED BY SO MANY TO SO FEW. “

I was born on the 8th August 1940 under German occupation on Jersey, so was surprised to see that my birthday was day one of the Battle of Britain. It is a wonderful tale of the British standing up against evil. That we were victorious is indisputable. Hitler gave up and turned East to fail again in Russia. Park’s report is typical of the way the best British people do things.

Would that we could show the same guts and determination now to rid ourselves of the present ills of the European Union.

Keith Park, wasn’t exactly British, but a member of the British Empire. As with a lot of heroes of the War, he was in Fact a Kiwi .There is a very good section of the Tech Museum in Auckland named for him featuring a collection of Aircraft.