In the middle of the First World War centenary period we find ourselves marking the bicentenary of the end of the original Great War – the one fought between 1793 and 1815. With only a brief hiatus in 1802, the legacy of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars has been somewhat overshadowed by more recent conflicts; nonetheless, for 19th century Britons and other Europeans, Waterloo marked a pivotal moment. It was the end of an era and the beginning of a century of relative peace on the continent. As with the worldwide conflicts that defined the 20th century, this war of more than 20 years placed enormous strains on the people of the nations involved and altered the shape of the continent in its aftermath. Rather than pick apart the intricacies of what happened on 18 June 1815, however, this blog will try to put the Battle of Waterloo into context using some of the documents in The National Archives’ collections.

Despite providing a definitive end to the Napoleonic Wars, the Battle of Waterloo did not come at the end of the 1814 campaign, but instead followed another brief pause in hostilities. After his misadventure in Russia and a loss of control in Spain, Napoleon still managed to inflict tactical victories on the encroaching powers of the Sixth Coalition – Austria, Prussia, Russia, the UK, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and various German states – as he retreated towards Paris in 1814. He was, however, unable to prevent the coming defeat and so delayed the inevitable by abdicating, agreeing to the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau.

Instead of a humiliation or long and distant internment, the treaty placed Napoleon in exile on the island of Elba, off the coast of Italy. The treaty offered an unusually lenient list of concessions, including the retention of his titles, sovereignty over the island and a bodyguard of more than 400 men. Recognising that such an agreement would acknowledge the legitimacy of Napoleon’s power and leave the door open for further conflict, Lord Castlereagh refused to sign the document on behalf of the British Crown. Nevertheless, Elba would be the French emperor’s home during his brief incarceration.

Elsewhere, emerging disagreements between those attempting to dictate the peace at the Congress of Vienna – the body established to settle the many issues arising from the Napoleonic Wars – distracted attention from their restless prisoner. Seizing the opportunity, Napoleon slipped away from the island with his Imperial Guard, later landing on the French coast.

Thus began his Hundred Days – a northerly march during which he steadily gathered strength from the disaffected peoples of the country as well as defecting army units. It was this unlikely series of events that delivered Napoleon to the field of Waterloo at the head of a reinvigorated French army in June 1815.

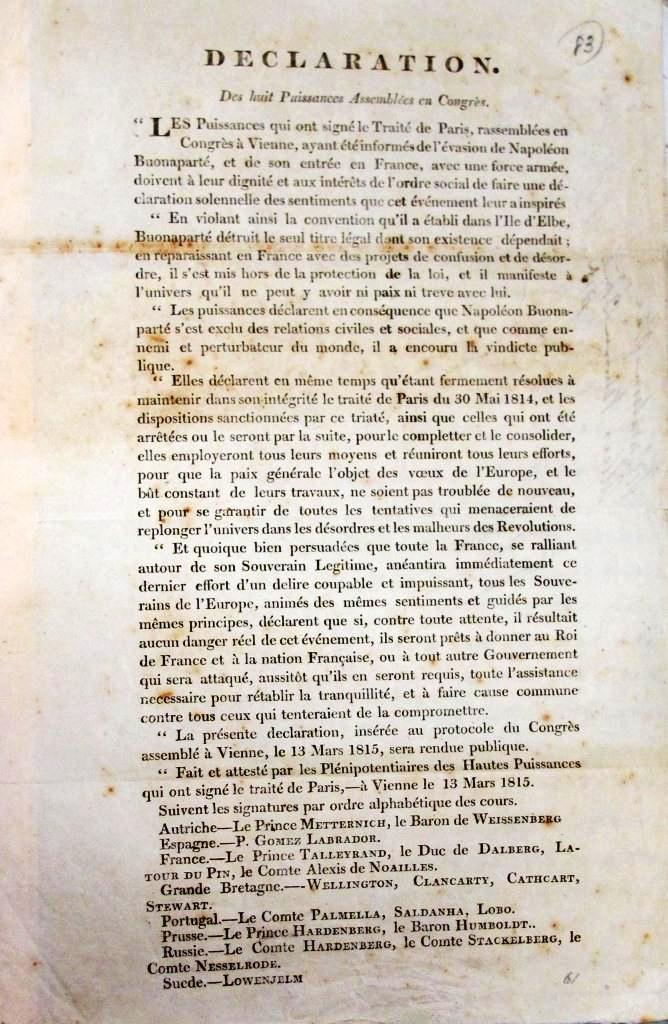

Observing the need to act decisively, the Coalition Allies inserted a declaration into the protocol of the Congress of Vienna on 13 March 1815 (shown below).

Declaration of the Allies at Vienna regarding the return of Napoleon (catalogue reference: WO 37/12/10)

Translated it reads:

‘The Powers who signed the Treaty of Paris, having reconvened at the Congress of Vienna and having been informed of the escape of Napoleon Buonaparte, and of his arrival in France with an armed force, owe it to their dignity and the interests of the social order to make a solemn declaration of their feelings.

In violating in this way the convention established on the island of Elba, Buonaparte is destroying the only legal title upon which his existence depends: in reappearing in France with plans to foment confusion and disorder, he has placed himself outside the protection of the law and makes it plain to the world that there can be neither peace nor truce with him.

The Powers declare in consequence that Buonaparte has excluded himself from all civil and social negotiations, and that as an enemy and destroyer of world peace, he has incurred the public condemnation. At the same time they declare that being firmly resolved to maintain in its entirety the Treaty of Paris of 30 May 1814, and the provisions sanctioned by this treaty … they will employ all the means at their disposal and will combine in their efforts so that the general peace, which is the wish of Europe and the constant goal of their work, should not be troubled again and to ensure against all attempts that threaten to plunge the world back into the disorder and misfortune of Revolution.

Although they are convinced that the entire nation of France, rallying around their Legitimate Sovereign, will immediately destroy this last effort of a reprehensible and impotent madman, all the Sovereigns of Europe, driven by the same feelings and guided by the same principles, declare that if, against all odds, any real danger was to occur from this event, they would be ready to give to the King of France and to the French nation, or to any other government which was attacked, upon request, all necessary assistance to re-establish peace, and to make common cause against those who might try to compromise this peace.’

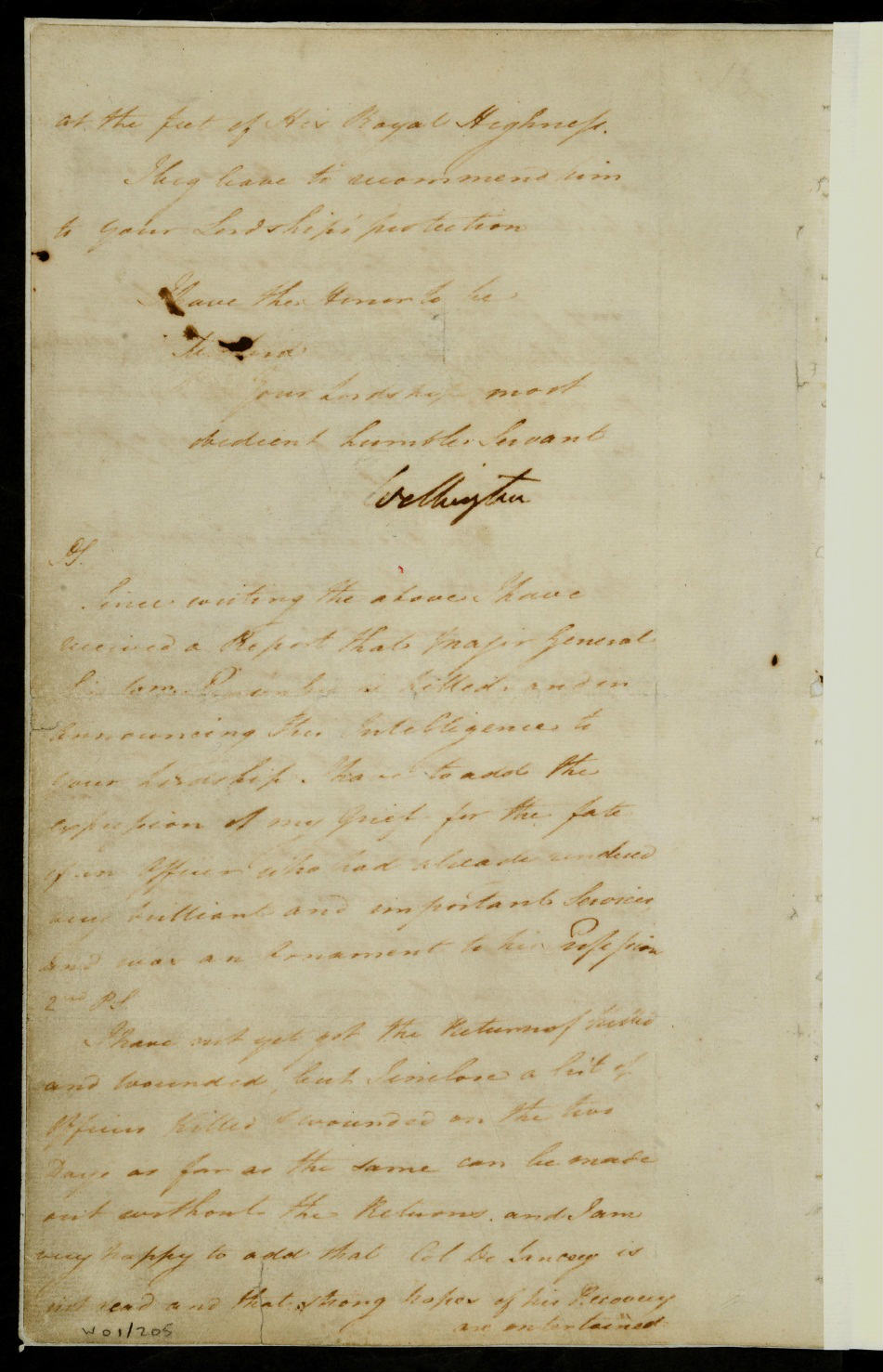

Final page of the Duke of Wellington’s account of the Battle of Waterloo, 19 June 1815, to Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War (catalogue reference: WO 1/205/2)

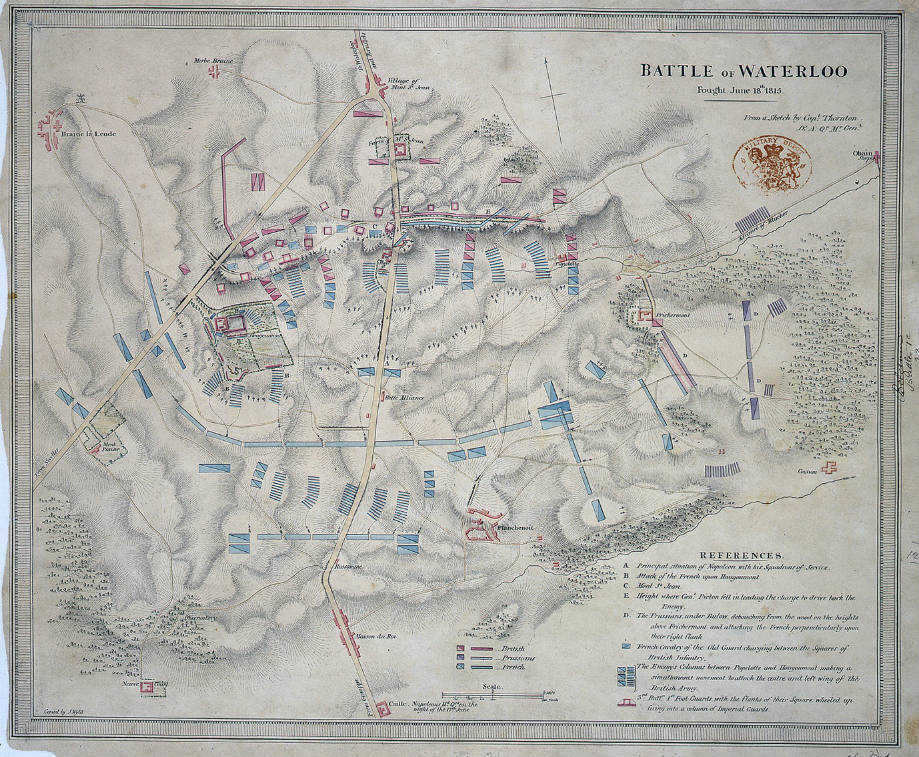

As is well known, the nation of France failed to rally around their legitimate sovereign and instead followed the ‘reprehensible and impotent madman’ into a bloody and decisive battle that finally brought a close to this turbulent period of history. A detailed account of what happened at Waterloo on 18 June 1815 can be seen written in The Duke of Wellington’s own hand in our Keeper’s Gallery, where his original despatch is currently on display alongside a map of the battlefield produced by Captain Thornton of the Royal Engineers (extracts alongside and below).

Map of the battle from a sketch by British officer, Captain Thornton, Royal Engineers, 1815 (catalogue reference: WO 78/1006/25)

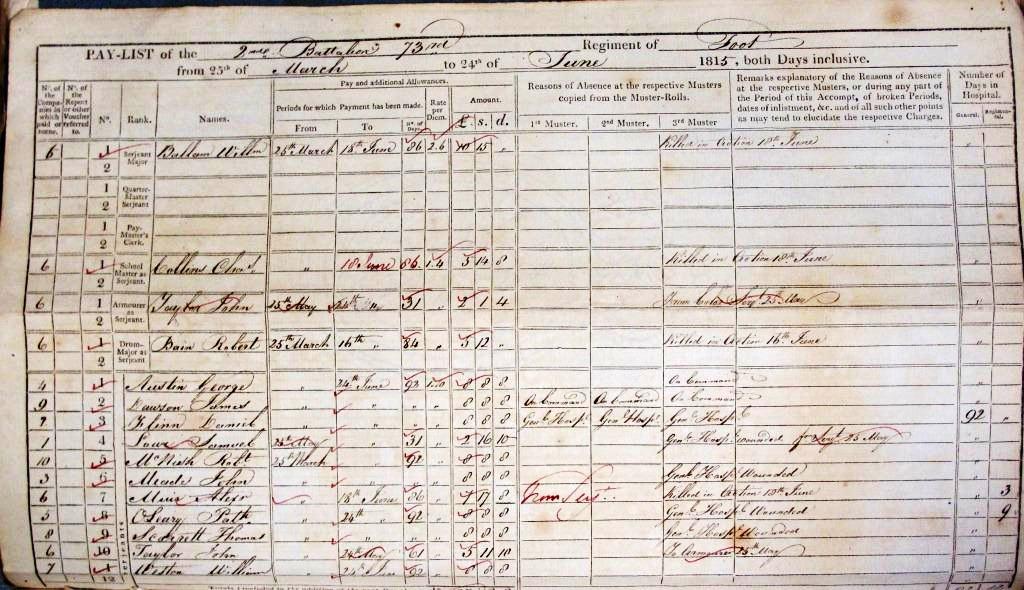

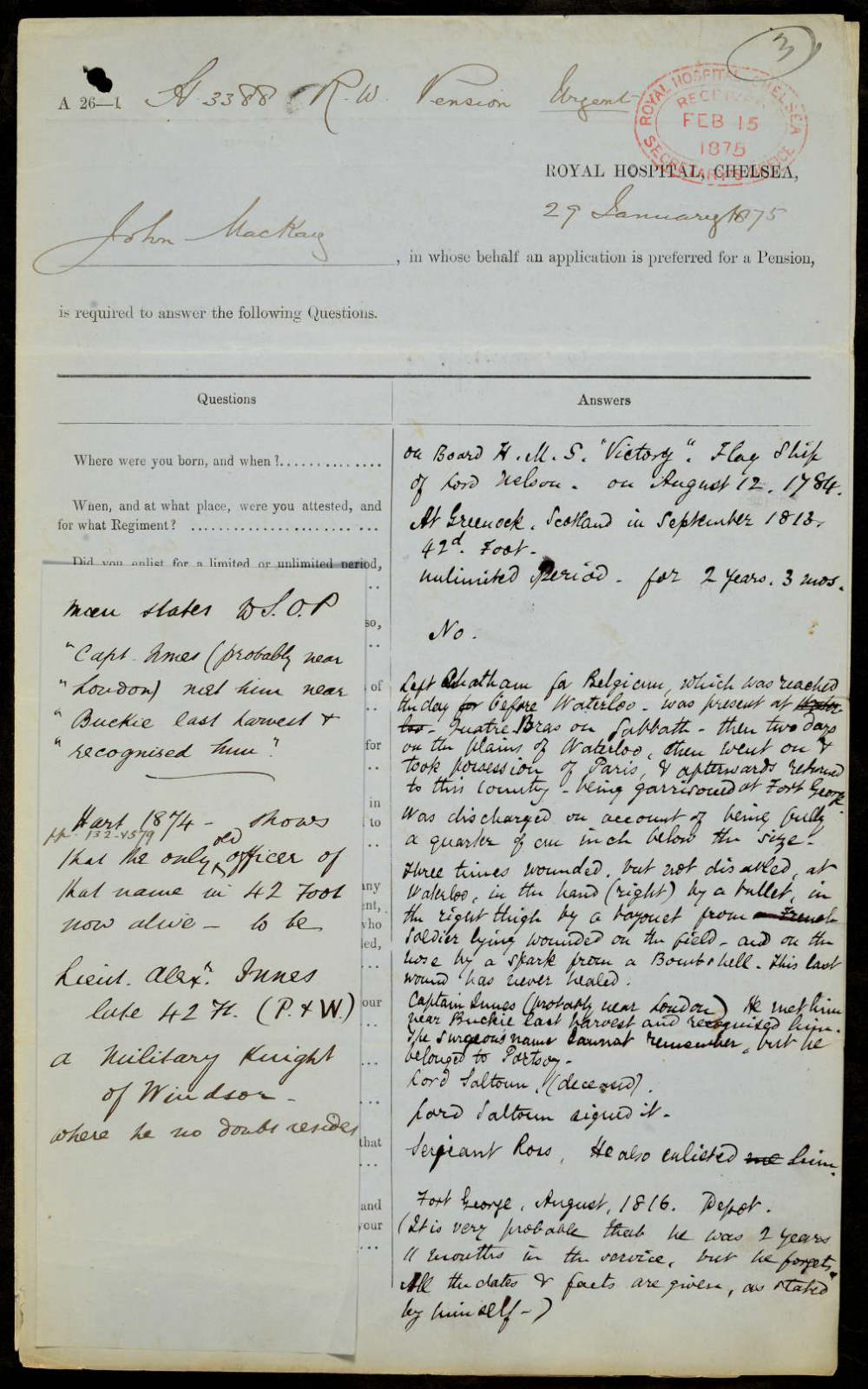

The exact human cost of the battle has proved contentious, although tens of thousands lay injured or dead in the open fields in its aftermath. Although some of the officers killed were repatriated, the final resting place for most soldiers was an unmarked mass grave. Despite this less than glorious end, participation in the battle can be traced through the musters and pay lists, pension records and medal rolls held in our collections – some example of which are below.

A page from the quarterly pay list of the 2/73rd Regiment of Foot showing those wounded and killed in action between 16-18 June 1815 (catalogue reference: WO 12/8062)

Discharge papers of Private John MacKay of the 42nd foot. He was wounded three times and was one of the last Waterloo survivors, dying aged 101 in 1886 (catalogue reference: WO 97/2036)

Waterloo medal, the first issued by the British government to all soldiers who had fought in a battle (catalogue reference: EXT 11/134) Medal rolls are found in WO 100 and can be downloaded for free.

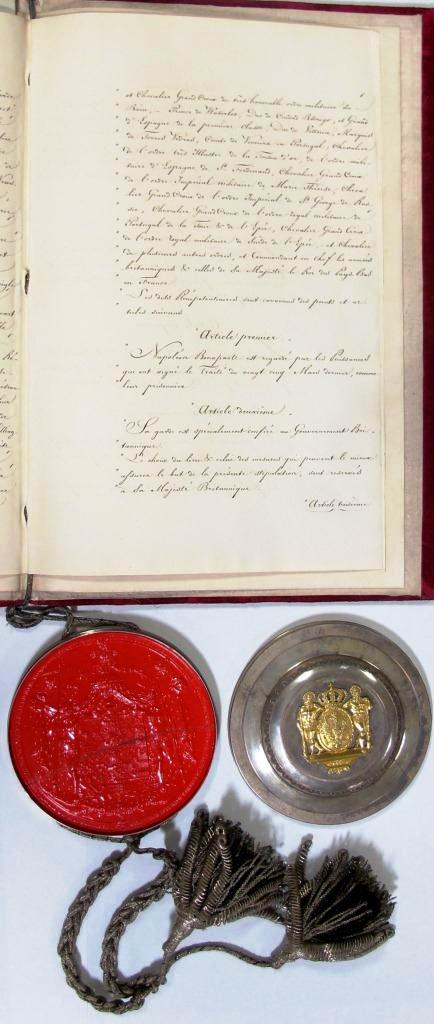

Following his defeat, Napoleon Bonaparte abdicated for a second time on 24 June 1815. On 2 August, Wellington and Viscount Castlereagh signed agreements with Austria, Prussia and Russia regarding the custody of Napoleon. The articles laid out that the guardianship and place of confinement of Napoleon would be conferred exclusively to the British Government.

Ratification by Prussia of the Convention for the imprisonment of Napoleon Bonaparte (catalogue reference: FO 94/193)

Beyond what is demonstrated in the incredibly significant documents shown here and on display in the gallery, the legacy of Waterloo was far reaching. The foreign policy developed by Viscount Castlereagh, who presided over the Congress of Vienna, became one of maintaining the balance of power in Europe by encouraging the spread of constitutionalism, especially in southern and central Europe. It would be 40 years before Britain would face a comparably devastating conflict (The Crimean War) and a whole century before she would face another ‘Great War’ on a global scale.

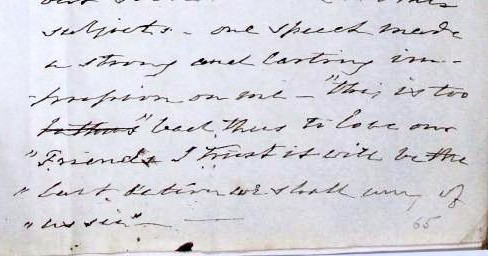

Writing in the aftermath of the battle, General Sir George Scovell, attached to the personal staff of the Duke of Wellington, sent a despatch to the War Office (above). Outlining his experience and describing his discussions with the Duke over dinner following the victory, he noted: ‘One speech [made by the Duke] made a strong impression on me “This is too bad, thus to lose our friends! I trust it will be the last action we shall any of us see!”‘

The Waterloo display is in the gallery until 25 September 2015. The display in the gallery features the Duke of Wellington’s account of the battle, the map of the battle from a sketch by Captain Thornton, the discharge papers of Private John MacKay and the Waterloo medal.