Agincourt, Trafalgar, Waterloo, Fashoda, Mers-el-Kebir… With the England-France rugby game drawing closer, these are very much on my mind. French supporters travelling on the Eurostar, however, will have a fair bit of time (two hours and twenty-six minutes) to reflect on that tunnel linking our two nations and cutting through, as Shakespeare put it in Richard II, ‘the silver sea, which serves England in the office of a wall, or as a moat defensive to a house, against the envy of less happier lands’.

Eurostar celebrated its 20th anniversary last May, but the idea of a tunnel dates back to the early 19th century. As the Peace of Amiens, ending hostilities between Britain and France, had just been signed, French engineer Albert Mathieu-Favier put forward the idea of a tunnel used by horse-drawn vehicles and lit by candles. The Peace of Amiens, sadly, lasted but one year, and the project was shelved. It gathered dust until another French engineer, Aimé Thomé de Gamond, teamed up with British engineers Low and Brunlees and defended a project involving a tube surrounding a double railway. This project was received with great enthusiasm by Emperor Napoleon III and Queen Victoria, who reportedly tended to get sea-sick; the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, who may not have ever suffered from sea-sickness, opposed the scheme.

After the Universal Exhibition of 1867, public opinions on both sides of the channel looked favourably upon any project aiming at bringing nations together. Projects were submitted to the French Emperor in 1868 and an Anglo-French Committee promoted the idea of a fixed link until the Franco-Prussian war put everything on hold in 1870.

The idea soon resurfaced and a Channel Tunnel Company was finally created in 1872, and a full report submitted in 1874. In 1875, France granted the promoters of a tunnel a contingent concession: should the public utility of the project be recognised in the next five years, they would obtain a definite concession for 99 years and a monopoly for 30 years; the capital was to be found half by the Chemin de Fer du Nord (the French Northern Railway Company), one quarter by the French House of Rothschild, and one quarter by the promoters themselves. The English Company didn’t obtain any concession, only the right to conduct experiments at St Margaret’s Bay, for which they proposed to raise a capital of £80,000.

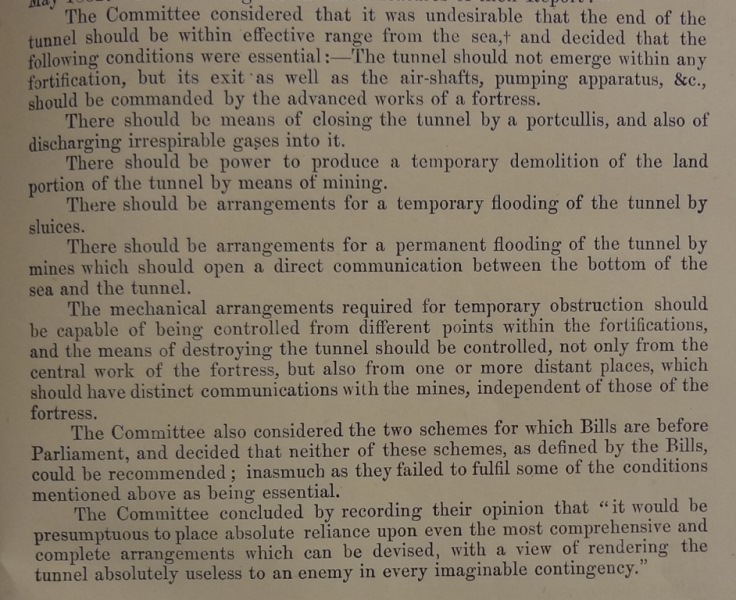

In Britain as in France, no particular effort was made to reach the treaty stage. On 2 August 1880, as five years had elapsed and nothing much happened (although the boring had begun), the French promoters were compelled to apply for an extension of their concession. In the meantime, a rival scheme was put forward in England by the South Eastern Railway Company. This prompted the creation of yet another committee composed of representatives from the War Office, the Admiralty and the Board of Trade. It was superseded by a wider committee instructed ‘to make a full and exhaustive investigation from a scientific point of view (and without reference to the ulterior question of national expediency) into the practicality of closing effectually a submarine railway tunnel’ in case of war. The Committee completed their report in May 1882. Work had stopped in April, and never resumed, mainly for reasons of national security.

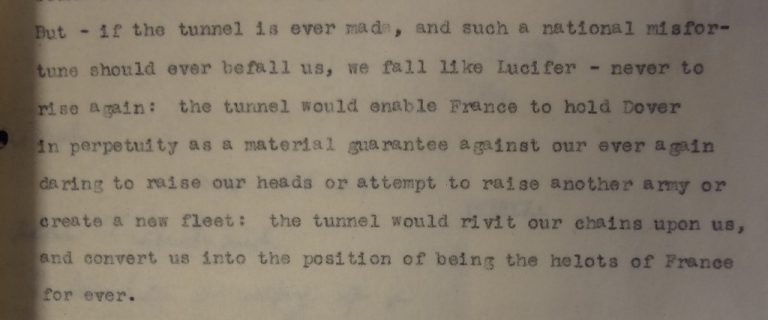

In Britain, from 1802 to 1987 and beyond, the opposition to the Channel Tunnel was based on financial arguments, of course, but also on much more subjective ones linked to the British attachment to insularity and mistrust of the French. Even the military arguments, which could have been perceived as logical, took a somewhat melodramatic turn. In 1882, Sir Garnet Wolseley, who successfully invaded Egypt later in the year, almost begged the government to renounce to a scheme which would destroy the value of the Channel. ‘As long as England remains unconnected by a tunnel with France, we could always recover from the effects of a successful invasion,’ he wrote, ‘but if the tunnel is ever made, and such a national misfortune should ever befall us, we fall like Lucifer – never to rise again.’

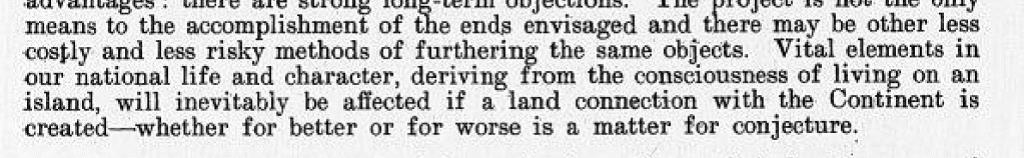

These security concerns and reassertions of the quintessentially insular character of Britain were a major stumbling block in the Tunnel’s history. The Foreign Office had warned, in 1875, that ‘the construction of a tunnel must necessarily, to a certain extent, impair the insular position of Great Britain’, and a Cabinet memorandum of 1949 implied that ‘vital elements in our national life and character’ were at stake.

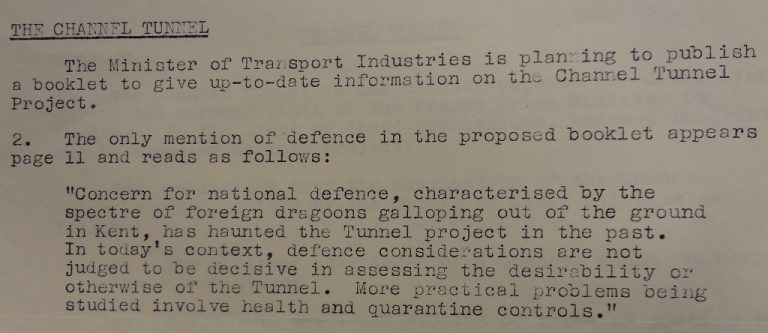

The spectre of a French (or, let’s be fair, German) invasion was raised every time the Channel Tunnel issue was mentioned in Parliament (35 times between 1882 and 1950), and all the bills (10) were rejected. Paranoia reached as far as fiction: How John Bull Lost London; Or, the Capture of the Channel Tunnel, published in 1882, describes the invasion of England just after the opening ceremonies by French soldiers posing as tourists. Objections linked to national security might have been valid in the 19th century, but they did seem a bit pointless in the age of the nuclear bomb… In 1971, the Ministry of Transport and Industries’ booklet on the Channel Tunnel Project even mocked the deeply-rooted military reluctance towards a fixed link: ‘Concern for national defence, characterised by the spectre of foreign dragoons galloping out of the ground in Kent, has haunted the Tunnel project in the past. In today’s context, defence considerations are not judged to be decisive in assessing the desirability or otherwise of the Tunnel.’

‘The spectre of foreign dragoons galloping out of the grounds in Kent’. Catalogue reference: DEFE 11/921

Military objections gradually weakened but some politicians remained staunchly opposed to the idea of a tunnel. While the Defence Chief of Staff declared in 1959 that there were ‘no valid military objections to the project’, Sir Stafford Cripps, the Chancellor, noted: ‘This seems a vast waste of time.’

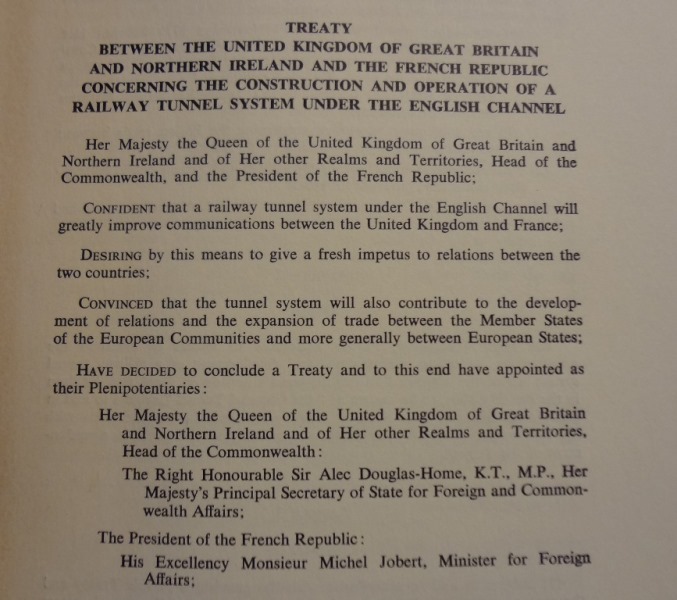

On 30 January 1964, however, the Cabinet agreed in principle to proceed with the construction of the Channel Tunnel, ‘provided agreements could be reached with the French regarding technical and financial arrangements and the timing of the construction.’ In June, the governments signed a protocol setting up a joint commission of surveillance for the geological survey to review things yet again. A treaty was finally signed on 17 November 1973, and about a mile of tunnel from the English coast was bored.

Treaty concerning the construction and operation of a railway tunnel system under the English Channel, 17 November 1973. Catalogue reference: FO 93/33/514

In 1975, although there was definitely no military objection, since article 15 allowed both countries to severe the fixed link in case of danger, Britain bailed out again – for financial reasons.

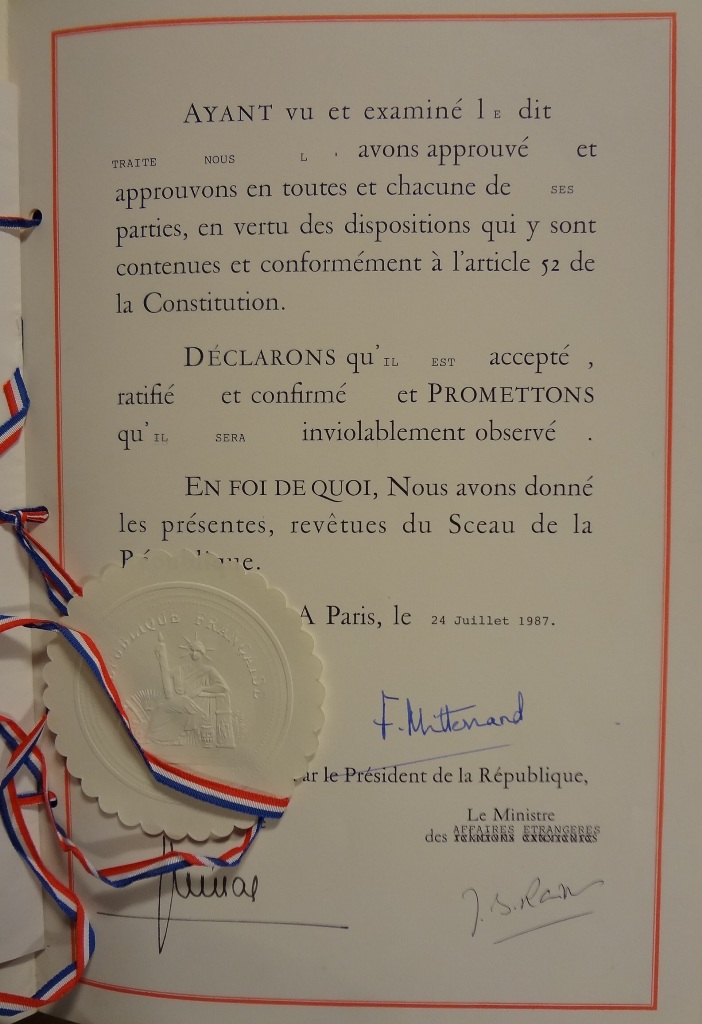

This ‘sleepy project’, as a Treasury official put it in 1965, was revived during the 1981 presidential visit. When Prime Ministers Thatcher and Mauroy met in May 1982, they discovered that they shared ‘a dream of a fixed link’. Only, Margaret Thatcher wanted to drive to Paris while Mauroy wanted to take the train to London (a compromise seems to have been reached since you can today put your car on a train to cross the Channel). Yet another joint study group was formed to go over all the now familiar issues of traffic, types of link (Mrs Thatcher thought a bridge should not be discounted), economic evaluation (would it kill the cross-Channel shipping trade?), environmental costs (would rabid animals infiltrate Britain from the continent?)… Its final report was agreed in April 1982. It was clear that neither France nor Britain could bear the cost of such an enterprise, so they decided to hold a contest. Four years later, during a joint ceremony in Lille, Mitterrand and Thatcher announced their support for a project put forward by Channel Tunnel Group and France Manche; the fixed link would take the form of three submarine tunnels (two running tunnels and a service one) and would have a total length of 49.2 kilometres. A treaty was signed and ratified in 1987. It would take about 13,000 workers over 7 years to dig the tunnel. The pilot tunnel met in the middle of the channel on 30 October 1990. Well, not exactly in the middle – the British dug a bit more but, I hasten to add, the French faced more difficult terrain.

The Channel Tunnel officially opened in 1994, with President François Mitterrand and Queen Elizabeth part of the maiden voyage to Waterloo Station (Waterloo!!). There were very few projects against which existed a more enduring prejudice than the Channel Tunnel but, from that date, Britain almost ceased to be an island. The Tunnel, which had come close to reality in several occasions, was finally real; it was, as a Treasury memo sardonically put it in 1930, ‘a triumph of hope over evidence’.

[…] tra la Francia e la Gran Bretagna. Nei giorni scorsi, la storica francese Juliette Desplat ha raccontato la storia dei progetti del tunnel sotto la Manica sul sito degli archivi nazionali […]