So far in our series of blog posts for the First World War Military Service Tribunals we have focussed on individual applications for exemption from our collection of case papers for the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal.

As well as these fascinating case papers the collection also contains a number of pamphlets, booklets and instructions issued to the various levels of Tribunals from Government departments, such as the Local Government Board and Home Office.[ref]1. The National Archives, MH 47/142, Blank forms, Circulars, Pamphlets issued by Local Government Board and other Government Departments, with printed Acts, Proclamations, Booklets, etc.[/ref]

When analysing these administrative documents, we begin to see the complicated position that Tribunals across the country found themselves in when hearing applications or appeals for exemption.[ref]2. For a detailed assessment of Tribunal work see, James McDermott, British Military Service Tribunals: ‘A very much abused body of men’ (Manchester University Press, 2011).[/ref]

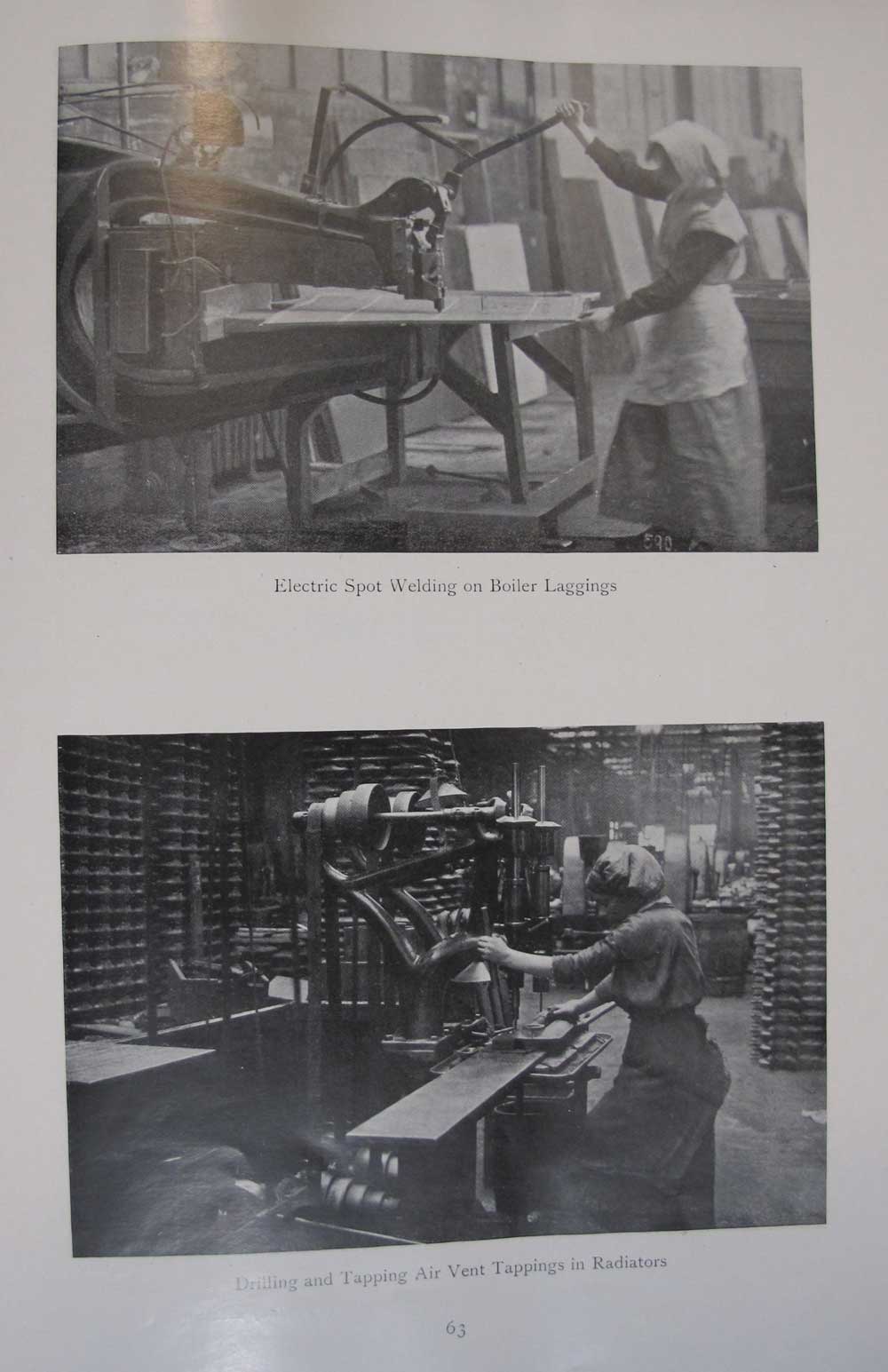

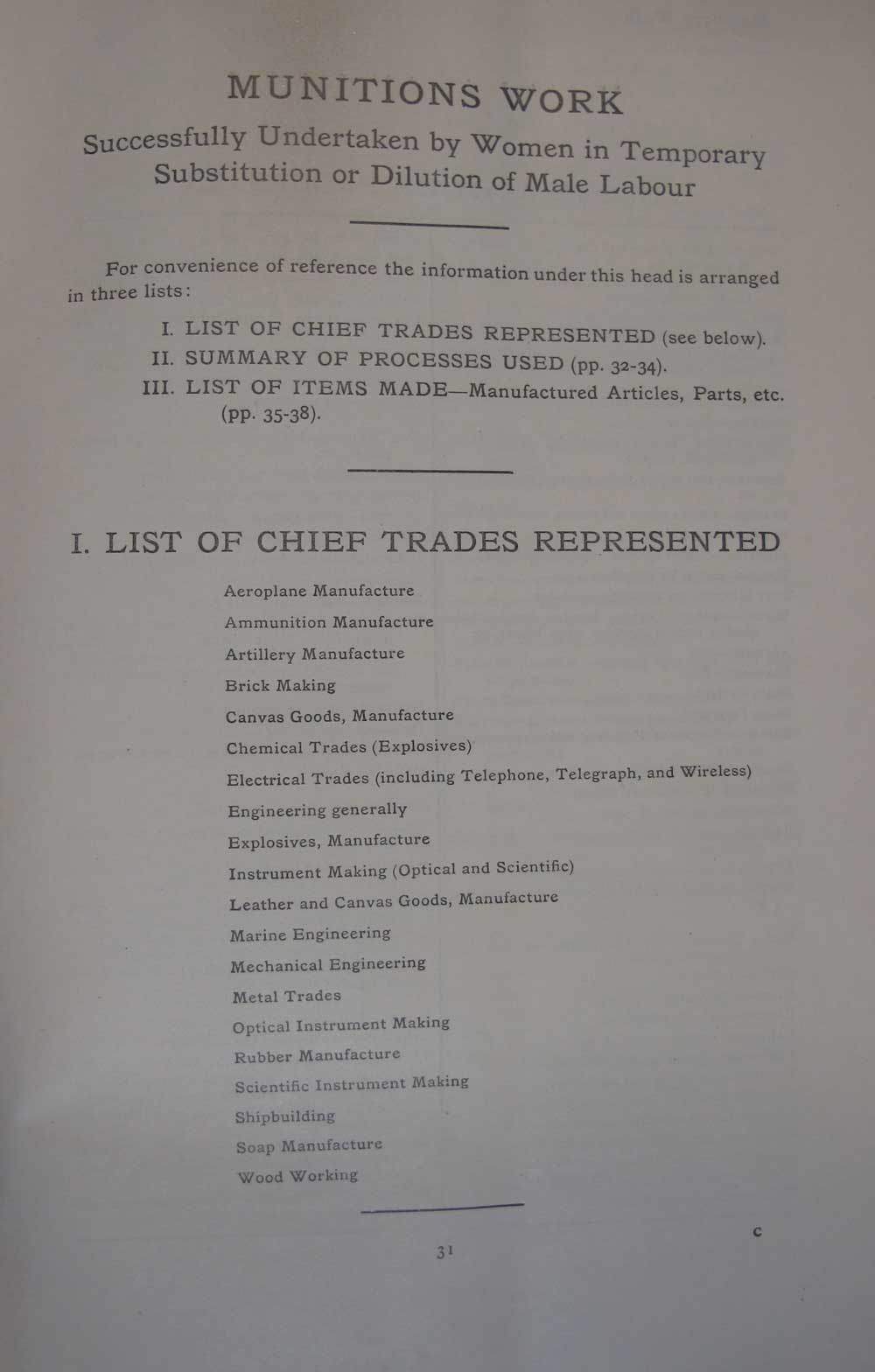

Included within piece MH 47/142 is a booklet titled, Women’s War Work, from September 1916 (pictured above and below). In it are listed about 2,000 positions which the Government were encouraging Tribunals, Military Representatives and local employers to substitute female workers in place of male employees of military age.[ref]3. TNA, MH 47/142, Women’s War Work (His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1916).[/ref] Substitution, it was hoped, would significantly help the country meet the two goals of winning the war and maintaining Britain’s position as the world’s leading trading power.[ref]4. Ibid, pp. 5-7.[/ref]

Photographs showing successful substitution of women for men from Women's War Work booklet (MH 47/142)

As James McDermott has found in his study of Military Service Tribunals of the First World War, however, the use of a substitution system did not always work as well in practice as it did in theory. In Northampton McDermott found that the use of substitutes in the well-established local boot and shoe required experienced employees to remain in place to provide training. Only when the new employees – both men and women – had reached a suitable level of competence would the experienced employee be released to join the army. A protracted process, which McDermott rightly states as being neither suited to the processes of the Military Service Tribunals, the needs of the Military Representatives or the output of the trade in question.[ref]5. McDermott, pp. 87-88.[/ref]

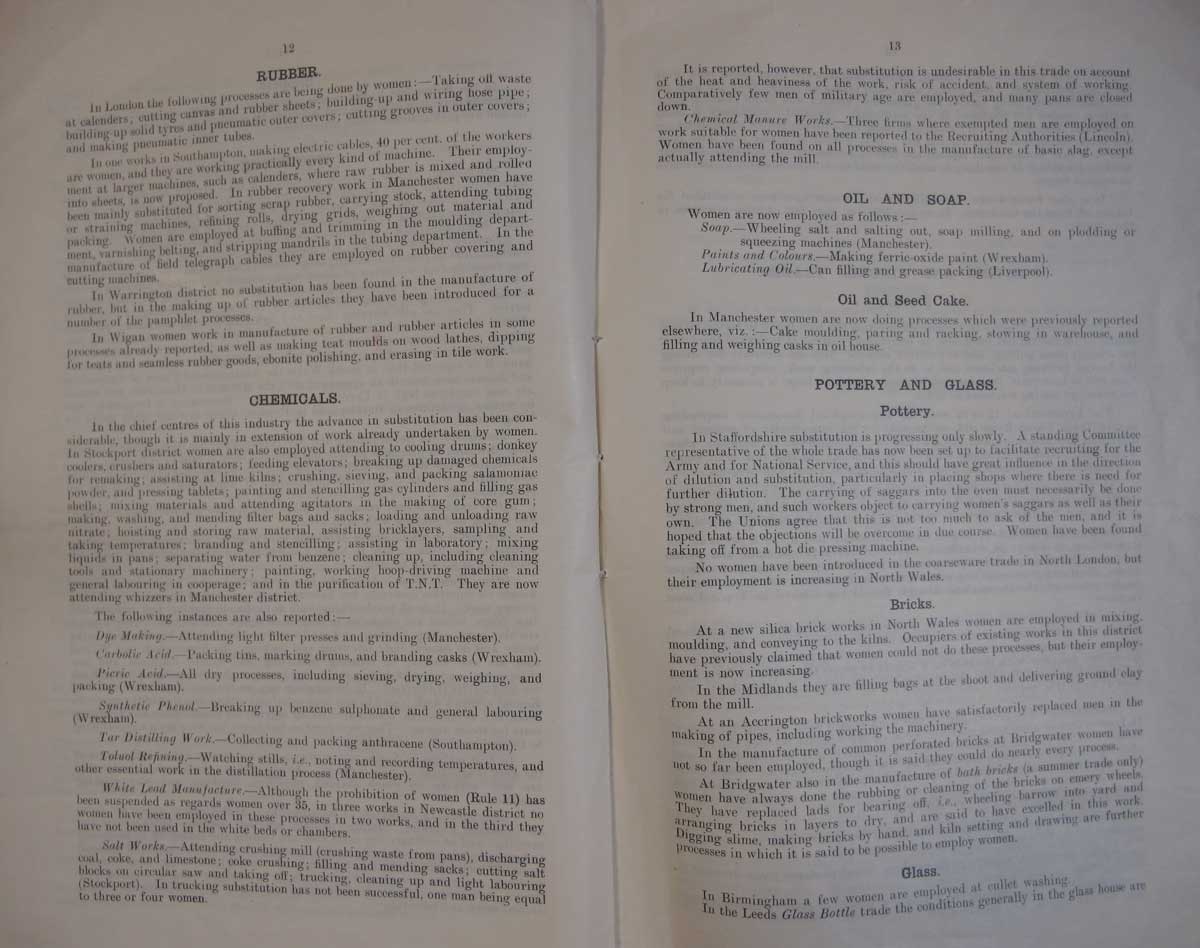

Back in the collection of papers in MH 47, a 1917 report summarising the findings of His Majesty’s Inspectors of Factories regarding the substitution of women for men found inconsistencies across the country as to the way female labour was being utilised. For example, Trade Union resistance to substitution was evident in the Weaving industry in Burnley, with Tribunals deciding against withdrawing exemption certificates for a group of male employees because ‘it is thought this would only aggravate matters’ with the Unions. Likewise in the Iron Founding industry, objections to female substitution had been found amongst male employees in Sheffield, Leicester and London.[ref]6. TNA, MH 47/142, Substitution of Women for Men: Summary of reports received from H.M. Inspectors of Factories, December 1916 to May 1917 (Home Office, 1917), pp. 4-7.[/ref]

Summary of reports, broken down by trade or industry, of successes and difficulties of implementing substitution (MH 47/142)

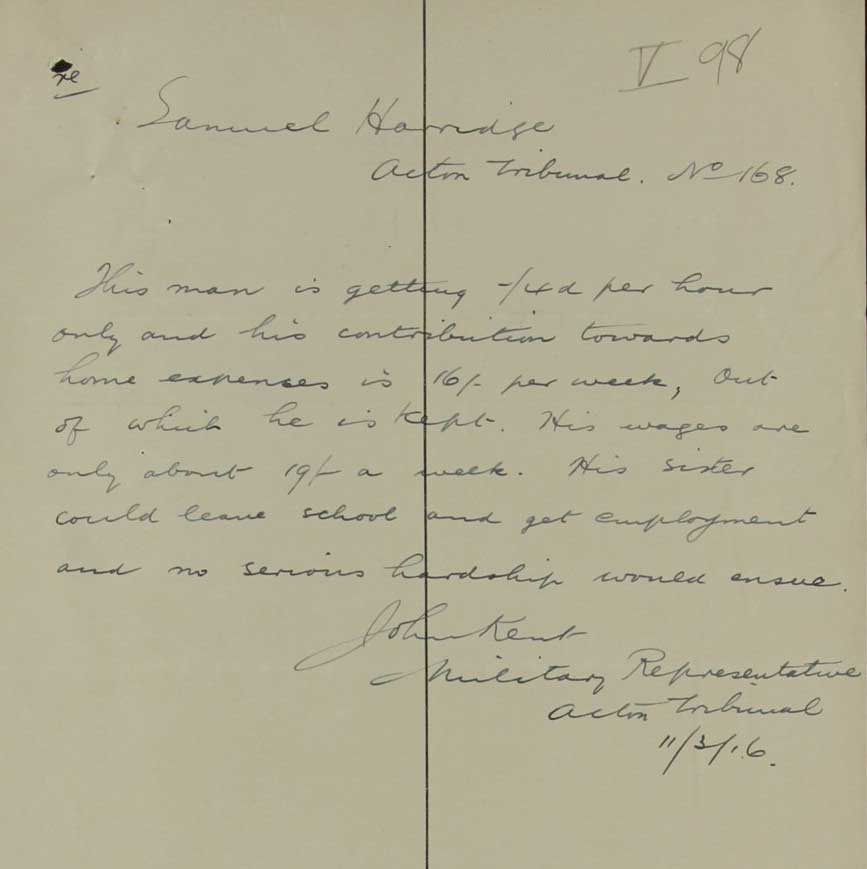

While it is evident that manpower policies such as substitution had its difficulties when implemented, the contribution made by substitute workers should not be under-estimated. As the case of Samuel Harridge at the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal shows, John Kent, the Military Representative, had advised the Acton Tribunal that Mr Harridge’s sister ‘could leave school and get employment and no serious hardship would ensure’ to the family.[ref]7. TNA, MH 47/72, Middlesex Appeal Tribunal, Case Papers: V. 98, Samuel Harridge.[/ref]Therefore, Tribunals were faced with making decisions that would affect a whole household, with significant personal sacrifices potentially being imposed on other family members. To use language of the sporting terraces, these people really were ‘Super-Subs’ for the considerable contributions and sacrifices they made for the British war effort.

Application for exemption of Samuel Harridge - Case paper: V.89. Letter from Military Representative to Acton Tribunal stating that applicant's sister should leave school and take employment (MH 47/72)

So, such instructions from Government departments to Tribunals across the country, as found in MH 47/142, reveal the complexities of Tribunal work. Decisions that would affect a whole family or household; balancing military needs with national industrial output; judging the impact on local communities if groups of employees were called up or if smaller businesses were forced to close; and needing to consider wider Government manpower initiatives, such as substitution, which they had no real control over.

Tribunal work was therefore a lot more complex than just dismissing an application for or granting an exemption from military service. Tribunals ultimately played a crucial role in helping our country meet the demands of Total War between 1916 and 1918 by being involved in a much larger, if a little haphazard, manpower policy.

Our project to digitise our collection of Tribunal papers in MH 47 continues to progress nicely. The last stages of image quality assurance work are now being tackled and we remain on course to complete the project early in 2014.

Please see our project webpage for further information, and please do keep your eyes peeled for further blogs from the project team in the coming weeks and months.

Thanks. One small point in that under footnote HM Stationery Office is mis-spelt, i.e. it is ‘ery’ rather than ‘ary’ (as in not moving).

Thanks for pointing this out – now amended.

Thanks for that David. Apologies for the error, which is mine alone.