Emil Otto Hoppé (1878–1972) is my kind of photographer. He was incredibly prolific, producing a huge body of work which spans many people, places and subjects (not likely to be pigeon-holed then).

He was not only a portrait photographer, as he was also known as a topographic and travel photographer. I am particularly interested in his travel photography, mainly because the images he took throughout his life document different kinds of places (from Indonesia to Australia) and show them in a different light.

What drove Emil Otto Hoppé to take photographs abroad?

Unfortunately, the records held at The National Archives aren’t necessarily going to provide in-depth or exact answers to that question. Even if you may not find all the answers to the questions asked in the course of your research, it shouldn’t stop you from asking (and looking) anyway. That’s the mystery of archives. Records don’t always tell you all the answers. They can be mysterious and enigmatic, and can often raise more questions.

It doesn’t mean you aren’t going to find any records though. The records I found relating to Emil Otto Hoppé by searching The National Archives’ catalogue capture his movements to various places.

Moving to London

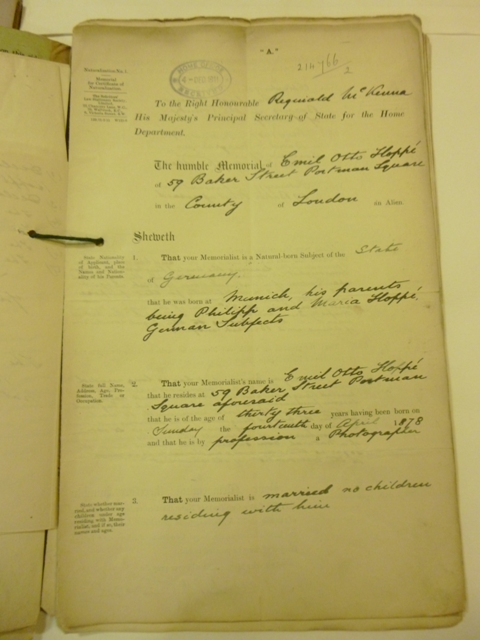

Hoppé first came to Britain to train as a financier in 1902, but later turned his hobby of photography into a career with great success. German by birth, the naturalisation case paper file in HO 144/1169/214766 reveals that he was born in Munich. It also provides personal details like his parents’ names and the signature of the applicant.

Some naturalisation case paper files may contain police reports which summarise the general character of the applicant and other details such as where they lived. Hoppé’s case paper file provides a brief summary of his places of residence, and therefore help us track some of his movements within London.

By the time he was naturalised in 1911, he already established himself as a commercial photographer based in Baker Street, London. The summary to the report held in the case paper file is ‘favourable. Applicant is a well-known photographer’.

Original correspondence in Colonial Office records

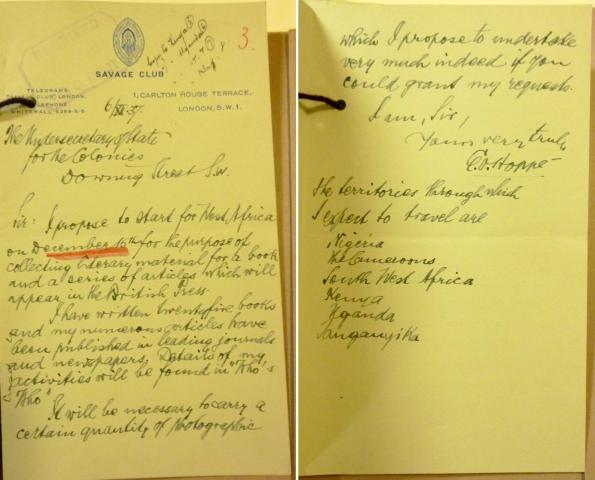

Extract of a letter by E O Hoppé on his intention to travel to Africa stating that it ‘will be necessary to carry a certain quantity of photographic material’ to take photographs. Document reference: CO 847/9/4.

We hold some documentation within the Colonial Office records which reveal some sketchy details regarding his expeditions abroad.

It’s the first time I’ve come across original correspondence within the Colonial Office files of a known photographer working abroad. The visits and expeditions file for Africa in CO 847/9/4 provides a summary of outgoing and incoming correspondence between Hoppé and the Secretary of the State for the colonies.

Not all the correspondence has been kept (within the summaries are stamps stating ‘destroyed under statute’) but the summary provides hints as to the content of the correspondence. The entries allude to queries regarding custom privileges and facilities to aid his photographic expeditions in West and East Africa.

Two letters written by Hoppé are also kept within the file. The letters contain a number of enquiries related to the trips to certain parts of Africa as part of research for a ‘series of articles which will appear in the British Press’. So although the file doesn’t go into detail about what drove him to take photographs in Africa, it indicates that one motivation is for work purposes.

British Empire Collection of Photographs (INF 10)

Evidence of his work abroad is also captured in the records. There are a small number of documentary photographs taken by Hoppé in the collection known asthe‘British Empire Collection’ within INF 10.

They are a far cry from the photographs displayed in the exhibition Hoppé Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in 2011, which featured portraits of well known figures such as George Bernard Shaw, Ezra Pound and intimate portraits of ordinary people.

Methodist school children in the Cayman Islands. Document reference: INF 10/92. © E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection / Curatorial Assistance, Inc.

The photographs in INF 10 depict people, places and subjects in the Cayman Islands within a given theme. The collection of photographs in each file contains a number of photographs, often by unnamed photographers, but some are stamped with the photographer’s name (for copyright reasons). This is quite common throughout this type of file within INF (and where named, is usually searchable by name within our catalogue).

Unnamed person preparing the leaves of Parlmetto Palms, ready to be split for fibre. Document reference: INF 10/95. © E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection / Curatorial Assistance, Inc.

According to our photograph specialist Steve Cable, press or agency photographers were often employed to take photographs abroad on behalf of the Central Office of Information. This could explain why the photographs were taken in a particular way, which deviates from the style of the known images often associated with Hoppé.

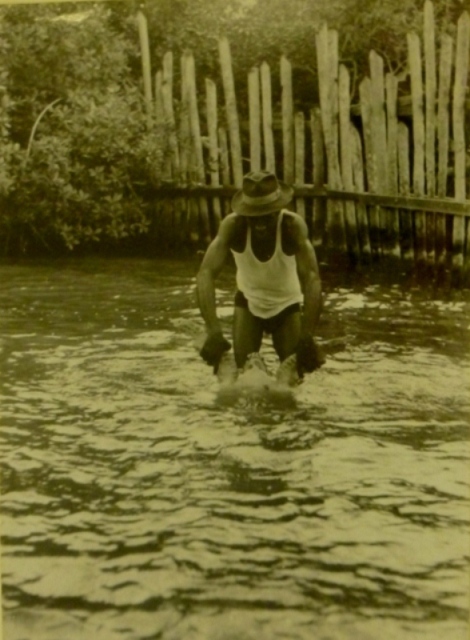

Turtle fishing. Document reference: INF 10/95. © E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection / Curatorial Assistance, Inc.

It is not clear why the photographs were originally taken and what purpose they served, i.e. whether or not they were originally intended for publication or whether they were taken to form part of a picture reference library for official use. But, as I said, with archives the pursuit of the answer often raises more questions.

Finding out more…

If this post has inspired you to carry out similar research, more information on case papers is in the guide on Naturalisation and British citizenship. For information on how to search for Colonial Office records, read our guide on Colonies and dependencies: further research or Administering the Empire 1801-1968: a guide to the records of the Colonial Office in the National Archives of the UK by Mandy Banton (Institute of Historical Research 2008).

Finally, if you are researching photographs, you may find our guide on photographs useful.

I was wondering why the photos shown appear to be blurred- unless it’s my eyes!

Same to teresa here; But from my experience at cobwebs design and as per knowledge our some photo shoots need not to posting commercial purpose;we do photo shoot for official purpose only ! thanks Emil for sharing some records & idea!

It would be very nice if you are able to include a little more photos in the article, and some higher quality ones if possible.

Teo

t-e-o.net

My family I believe is related to Otto Hoppe so known to us as Otto Hahn. His Daughters name Edith and wife’s name Margarete. We would like more information on your collection.

Dear Katie,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to family history, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.