LGBT History and Education at London Metropolitan Archives

This year’s LGBT History Month has been a special one for us at London Metropolitan Archives, marking the 10th year of our London Gay History Project, which culminated in our 10th LGBT History, Archives and Culture Conference, Brave New World? (already mentioned on The National Archives’ blog).

LMA’s London Gay History Project doesn’t just end with our conferences however. 2013 will see the launch of our LGBT History Education workshops, which allow young people to use documents from the LMA’s collections to explore themes in LGBT history.

With all of this in mind, I thought this blog would be a great opportunity to highlight and celebrate some of the LMA’s LGBT history sources…

As has been discussed on this blog before, one of the largest difficulties in researching LGBT history is that before the mid-20th century, the stories of people’s lives are often next to invisible, hidden away in the records of official bodies, using archaic language and usually lacking in detail. This makes researching LGBT history in archives quite a challenge (which is why The National Archives’ Discovery tags are such a good idea!), but I’ve been lucky enough at LMA to have most of the hard graft done already by our community archivist.

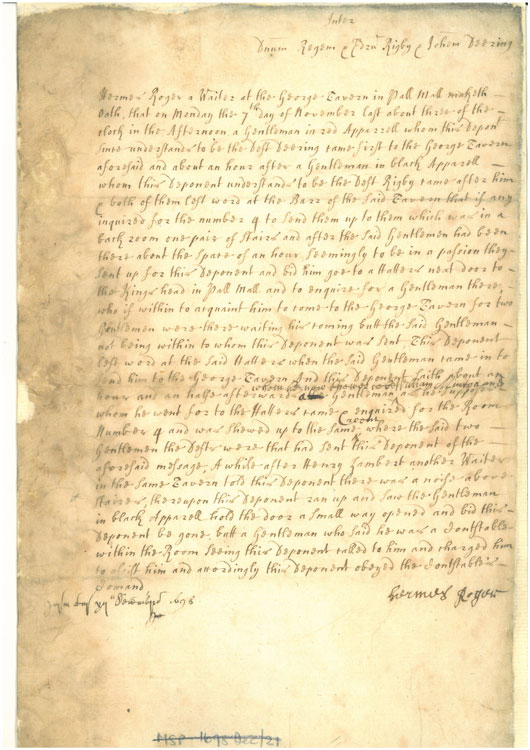

One of our most interesting early modern documents is the account of the trial for sodomy of Captain Edward Rigby, which took place in 1698 (LMA reference: MJ/SP/1698/12/024). It tells a fascinating story and paints an unusually vivid picture of homosexual life in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, further context for which I am indebted to historian Rictor Norton.

Rigby was a naval captain of some regard when he was indicted in what may be the first recorded instance of an agent provocateur being used to entrap someone. According to the evidence at the trial, Rigby had approached William Minton during the fireworks display in St James’ Park (then known in some sections of society as a gathering place for homosexuals) on Guy Fawkes’ night and, having kissed him (amongst other things) encouraged Minton to meet with him in the nearby George Tavern the next day in order for them to continue their liaison.

Minton, however, was an agent for the Societies for the Reformation of Manners, a vindictive association of aggressive moralisers, and his further liaison with Rigby was listened in on by constables, leading to him being charged, and convicted, for sodomy.

What’s remarkable about Rigby’s case is that he was aware of a tradition of homosexuality, telling Minton that their activity was ‘no more than was done in our forefathers’ time’. The late 17th and early 18th centuries saw an exponential growth in prosecutions for sodomy, as homosexuality ceased to be just an isolated personal experience and, in the capital at least, began to resemble a community. The best example of this were the ‘Molly Houses’ (‘Molly’ was a derogatory term form for a gay man), where homosexual men could meet and socialise without fear of persecution; except when ‘moralising’ forces intervened in cases such as Rigby and of the gay bookseller whose spell in the pillory was the subject of the homophobic ballad Molly Exalted, or This is Not a Thing (1762, LMA Reference SC/PD/XX/45/13A).

These documents are fascinating because they don’t just allow us to see how homosexuality was persecuted, but are also a tantalising glimpse of the emergence of a gay sub-culture in London, the visibility of which (however slight it was to the untrained eye) allowed those who would otherwise be isolated and alone to find an identity, although in turn making them more open to persecution. As historian Alan Bray puts it, this emergent alternative society became for a gay man ‘the cause of his alienation and the means of overcoming it'[ref]1. Alan Bray, Homosexuality in Renaissance England, Columbia University Press, New York, 1995, p.99[/ref].

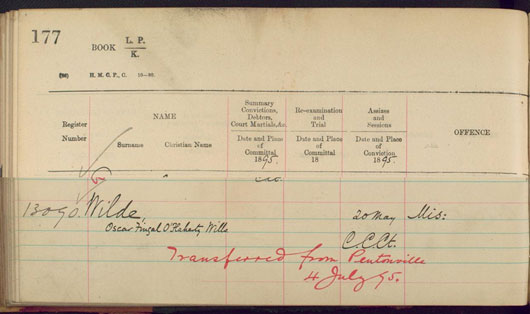

The flowering of gay sub-culture, however inconspicuous, and its brutal suppression by ‘society’ at large, is unfortunately a recurring theme in LGBT history. Another example is Oscar Wilde, who the LMA holds both a marriage and a prison record for. Wilde and his aestheticist companions were responsible for a revolution in British art, revelling in decadence and eroticism and once again bringing homosexual themes slightly more out in the open, after the rampant persecution of the earlier 19th century (between 1800 and 1806 more men were sentenced to death for sodomy than murder[ref]2. Paul Crane, Gays and the Law, Pluto Press, London, p.10[/ref]). Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray dealt with these themes in a mischievous and candid manner and journals like The Yellow Book caused controversy with the art and literature they published.

Sadly, Wilde was arrested, Dorian Gray being used as evidence in his trial. The brief notes of his details in the register of Wandsworth prison (ACC/3444/012/01/07) are all we hold at the LMA about this period of his life. A sparse, bureaucratic reminder of how the savage persecution by the media and the establishment destroyed the life of the great writer.

There are though, some happy stories in our collections as well, the collections of LGBT campaign groups which have taken on over the last ten years telling an inspiring story of a community’s struggle for recognition and equality.

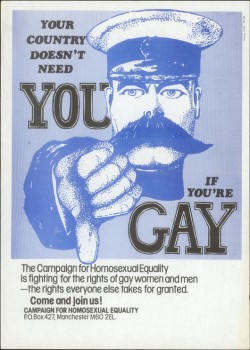

We are lucky enough to have the records of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality’s (CHE) Southwark & Lambeth group (LMA/4539). CHE formed in 1969 and was instrumental in furthering both legal and social equality for LGBT people, and also helped develop social and leisure facilities for the community, backing recreation centres, becoming heavily involved in Pride and setting up a switchboard to support young LGBT people.

Along with this we have the records of organisations such as Outrage!, Peter Tatchell’s LGBT campaign group (LMA/4466), and the magazine Lesbian London, which includes copies of lifestyle surveys completed by readers, allowing us a highly personal, often touching look at people’s lives.

It’s been heartening when developing the LGBT education workshops to look through these more contemporary records and learn more about these inspiring groups and individuals. One of our key concerns in the development of these resources is to not fall into the trap of presenting a narrative of victimhood.

Edward Rigby, you’ll be glad to know, escaped prison and absconded to belligerent France, where he resumed his formal naval profession with aplomb. The story of LGBT people in Britain is one that is, unfortunately, dominated by persecution, but archival materials, both those hidden amongst the ephemera of the past and those from contemporaneity, often allow us to peek at the lives of the talented, daring and often happy people who make up the history.

Thanks for the shout out to my previous post! I was terribly glad to get to the end of this and find out that we know Edward Rigby didn’t just stay in jail long term.

There is also a file on Edward Rigby at The National Archives (ADM 1/5260/110) where on 1 December 1698 Rigby was acquitted at a Naval Court Martial of beating two seamen.

Hi Melinda, that’s quite alright. It’s nice there’s a somewhat happy ending to Rigby’s story isn’t it. Apparently he was captured by the British Navy whilst serving with the French, but seems to of once again escaped! Alan Bray points out in his book that a lot of persecuted LGBT people in this period made good their escape from the authorities, it’s just not recorded in much detail.

David – Thanks for the headsa up, I’ll have to come to Kew and have a look at it. Rigby also seems to appear in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery’s collections. The portrait is dated 1702, but it is an engraving, so one presumes it was reproduced from a pre-trial picture…

http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitLarge/mw142099/Edward-Rigby?LinkID=mp61641&role=sit&rNo=0