The weird and the not so wonderful designs for London in LMA collections

As a trainee at London Metropolitan Archives, I take an active part in developing and implementing adult learning activities. These include a host of events ranging from workshops organised for community groups working on specific heritage projects, to talks and workshops open to all members of the public. The latter are informal sessions which use accessible narratives to provide an introduction to certain collections or topics.

The sessions I have led on so far have mostly been based on dynamic presentations followed by a ‘show and tell’ of original documents. However, for the upcoming session entitled Bad Idea! (11 September 2013), I decided to follow a slightly different structure.

The concept of the Bad Idea! session came out of a conversation about bad designs and flawed town plans. That conversation inspired me to send out an email to everyone at LMA asking for submissions of what they thought were the most outrageous or surprising designs for London, and I got some fantastic responses. Here are some of my favourites:

The ‘burial pyramid’, proposed by Thomas Willson in 1828 for a cemetery at Primrose Hill, would have had enough space for as many as 5 million individuals. This rather morbid design would have been taller than St Paul’s, and if it had been built on top of Primrose Hill as intended, it would have definitely dominated London’s skyline (as well as depriving us of one of London’s most popular spots for watching the fireworks on Guy Fawkes Night). It was one of many cemetery designs proposed around that time; eventually, George Carden’s grand design won and became the now famous Kensal Green Cemetery. Willson’s pyramid never saw the light of day.

Fog dispersing machine (City of London ref: SC/GL/WUL/001/013) Fog battery : air cannon or projectors for dispersing fogs, invented by Professor M. Demetrio Maggiora (Unidentified monogram) 1913

Another surprising design, created in 1913 by an anonymous author as part of a futuristic idea for ‘London of 1925’, proposed a fog dispersing cannon; its explosions, as the caption assures, would not be heard or felt in any part of the city. Truly revolutionary, but sadly never came to being.

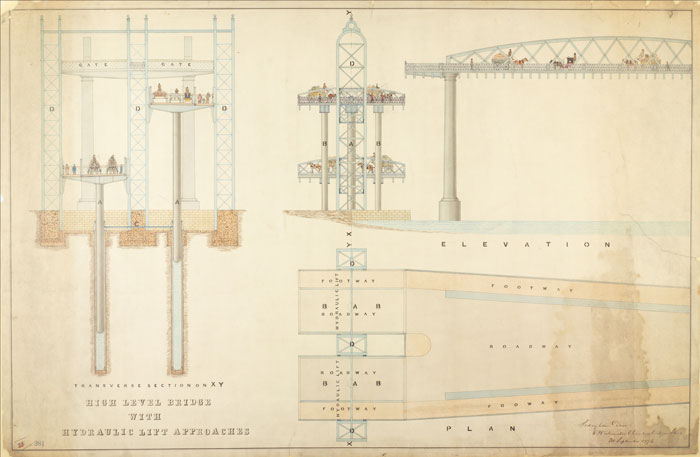

LMA also holds documentation for the Tower Bridge competition which includes, among many other somewhat extravagant designs, a plan for a ‘high level’ bridge, accessible by a hydraulic lift. One can only imagine what sort of queues would have been caused by having to wait for one of the two available lifts. I also think that while going up in this open-air lift would have been a thrill for most people, it would have been rather frightening for the horses!

Tower Bridge design (City of London ref: COL/SVD/PL/03/0279) Tower Bridge: Proposals, 1876 (Plan and elevation of a design for a high level bridge at the Tower; Scale 1/240; Unexecuted; T. Claxton Fidler)

Perhaps a little less spectacular but no less fascinating are some plans for a comprehensive redevelopment of Piccadilly Circus, dating from the 1970s, which caused considerable opposition at the time. Public protests against those plans are quite well documented in our collections, both in written reports and, surprisingly, in some videos produced by the Greater London Council itself.

In fact, public response to these plans and designs is one of the most interesting aspects of analysing them. This is why for this session, I decided on a more participatory format which means I will organise it as a discussion rather than a presentation. Gathering around a big table where these plans will be laid out, we will discuss why the same design might be deemed visionary and preposterous at the same time. I hope that in this way, this session will show the participants that interpreting archival documents doesn’t have to be as daunting as it may appear. As looking through these documents raises many issues – from the changing public conception of aesthetics in architecture, to developments in design technology, to tensions between conflicting interests of different groups – I am hoping for an afternoon of exchanging opinions and thoughts on all these aspects of urban design.

Preparing for this session also prompted me to think about archive accessibility from yet another point of view. The idea seems quite straightforward – bizarre designs that have never been built. But how do you research a topic like that in an archive? It’s hard to imagine that an item would be catalogued as an ‘outlandish design’. I was once again convinced that no matter how good the digital catalogue may be, there is nothing like human interaction when it comes to using the archives. As the catalogue entries for some of the ‘bad idea’ submissions reveal nothing about their unusual nature, tapping into the expertise of other members of staff was clearly the most efficient way of researching this topic.

Do you know of any other ‘bad ideas’ for London? Please share them with us in the comments section!

When cataloguing demonstrations negatives this week I came across negatives from a protest against the rebuilding of Covent Garden and Piccadilly Circus, taken for the Observer newspaper in 1972 – further evidence of the opposition you mention in your blog post.

Elisabeth, Trainee, Guardian News & Media Archives

Hi Elisabeth, thanks for that! It would be interesting to see those photographs – have they ever been developed or are they only available as negatives?

The GLC video I mentioned includes quite a number of interesting banners people carried with them to the protests, including one that says ‘LONDON BELONGS TO THE PEOPLE’ – I wonder if the photographs you found have more examples of those?