For hundreds of years, traders have put their particular marks or symbols on their goods to indicate ownership and quality. Trade marks are, in effect, a company’s ‘badge of origin’.

The National Archives holds a huge collection of trade marks, both the registers and the representations, registered from 1875 until 1938. Only six of the registers have survived; however, the representations (the designs themselves) have largely remained intact and are found in the Board of Trade series BT 82 and BT 244.

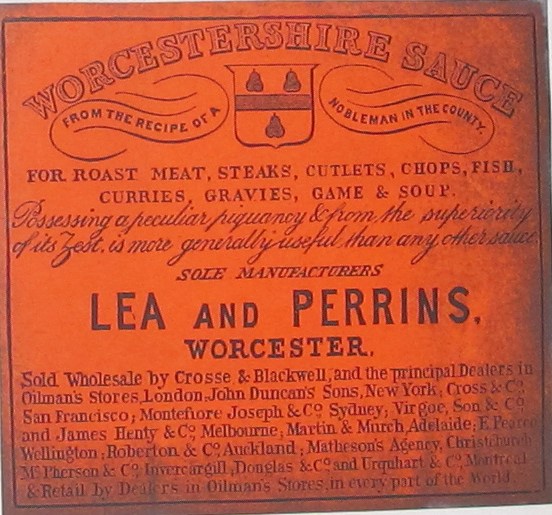

BT 82/1 (5), Lea and Perrins

In the latter half of the 19th century, trade marks were considered an invaluable part of the product and very much part of the marketing strategies of firms. These records form part of the movement to protect intellectual property in the late 19th century, along with Registered Designs and Copyright.

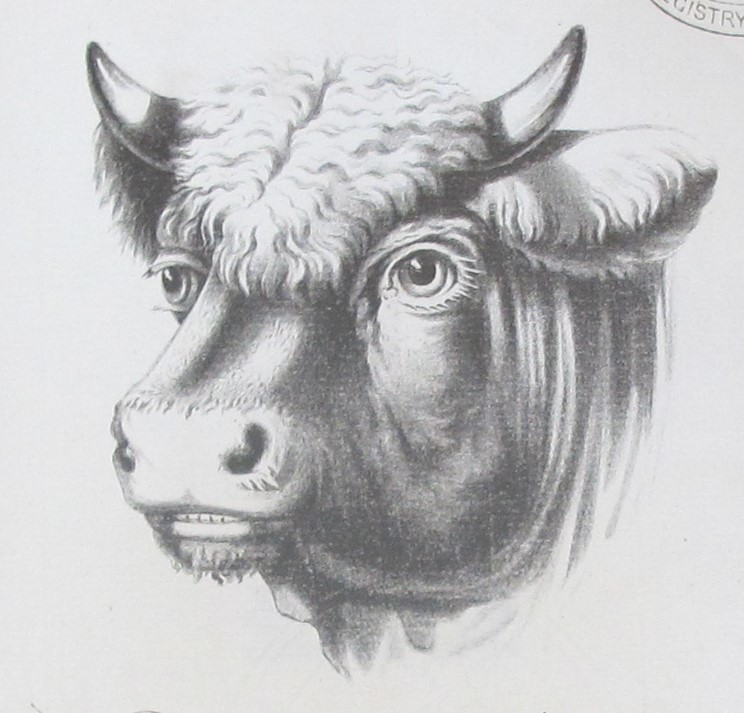

BT 82/1 (90), J J Colman

Our collection of the original designs and artworks for these early marks makes up a fascinating and intriguing set of records, hitherto largely ignored. These records throw light on the social mores of the time, and also into the early marketing background of numerous companies – many of which are still in existence today. Examples include Colman’s Mustard and Lea and Perrins Worcestershire Sauce.

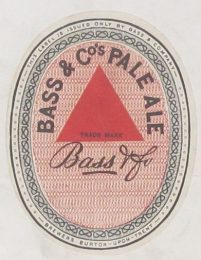

BT 82/1 (1), Bass & Co

Interestingly, other iconic designs registered in the 1870s are not only famous for their design properties, but also for other much more esoteric uses of their mark.

The Bass ‘red triangle’ trade mark appears among the bottles in Edouard Manet’s painting of ‘A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’, painted in 1882 and considered one of his major works. In around 1914, Pablo Picasso incorporated the ‘red triangle’ as a continuing motif in a series of 40 abstract works titled ‘Verre, Violon et Bouteille de Bass’. In 1925 the Spanish Cubist painter, Juan Gris, followed suit with his work ‘La Bouteille de Bass’.

Edouard Manet: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

- ‘Verre, Violon et Bouteille de Bass’ by Picasso

- ‘La Bouteille de Bass’ by Juan Gris

I think most amusingly, a very impressive testimony appears in ‘Fortunes Made in Business’, a book by James Hogg written in 1884, about Bass’s ‘red triangle’:

The sign of the vermillion triangle is sure evidence of civilization. That trade mark has travelled from China to Peru, from Greenland’s icy mountains to India’s coral strand….. You meet the refreshing label up among Alpine Glaciers and down in the cafes of the Bosporus, among the gondolas of the Grand Canal at Venice, the dahabeahs at the first cataract on the Nile and the junks of China….. It sparkles before the camp fire of the Anglo Saxon adventurer out in the wilds of the Far West and its happy aroma is grateful to the settler in the Australian bush. When the North Pole is discovered, Bass will be found there, cool and delicious.

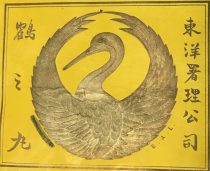

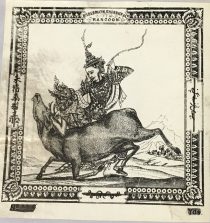

BT 244/440 (26909), The Eastern Agency Ltd

This excerpt shows the astonishing power this trade mark held as a global device midway through the 19th century. It is amazing to think that this small, simple design was recognised, even then, to hold such importance for the manufacturers and owner of this beer. It is still registered.

Trade marks, as now, were considered an invaluable part of the product. It was understood that valuable trade marks (or trade marks that were deemed valuable) had to be protected at all costs from any infringement, however slight. As a consequence, many companies felt the need to secure their exclusivity by registering as many variables as possible. We hold lots of examples where this happens.

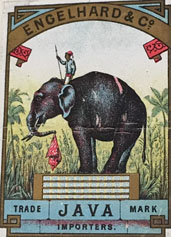

BT 244/440 (27321), Engelhard & Co

The general view of the first trade marks registered in 1876, just after the Trade Mark Registration Act 1875 came into force, shows some very simple marks with a complete lack of sophistication, while others registered were hugely complicated. As a generality, picture marks were more common than word marks, especially for those items which were made for export overseas.

The Lancashire cotton trade, in particular, sent materials to markets that fell outside western styles and fashions. Most Lancashire cotton goods were designed for export and, by the mid 19th century, this region was home to the largest export industry in the world. These were the industry’s major markets and supplied vast regions such as China, India and Africa – countries whose buying populations generally spoke little or no English.

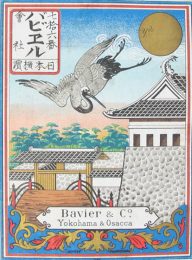

BT 82/36 (8798), Bavier & Co

It was, therefore, of crucial importance for merchants and manufacturers to pay close attention to the needs, customs and desires of the consumers of their goods. The role design played was invaluable in capturing these markets.

Manufacturers had to understand how these markets worked and trade marks played a key role as one of the integral component parts of design, production and export. The trade marks themselves had to reflect these markets – the traditions, tastes and fashions of these very different target consumers – in order to ensure the success of the goods being sold.

Many of these trade marks showed pictures of reptiles, unusual birds and human figures. Importantly, these appealed to the eye and created a symbolism that was easily recognisable in the countries to which they were being exported. They illustrated to the buyers the qualities the companies wanted to extoll. What these overseas consumers wanted, along with their design preferences, had to be translated into everything to do with the design and the marketing of these goods.

BT 244/440 (34054), Biedermann Sherriff & Co

These records are fascinating and, for me, real page turners. They give an extraordinary insight into the early design history of trade marks, both within this country and also for export. They also offer a fascinating glimpse into the mindsets and working practices of the companies, merchants and agents who functioned within these markets.

This was a very interesting blog, i’m sure it’s a fascinating subject area.

Colman’s, not Coleman’s Mustard! See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colman%27s

Hi Nigel

Thanks for pointing that out – I’ve corrected it now.

Kind regards,

Matthew

The need to take into account the abilities and familiarities of customers – that’s similar to earlier ages in this country when inns displayed their names as signs showing familiar objects, allowing for the many who could not read. The Black Bull, White Horse, the Gate, the Oak Tree, etc.

Hi Christine, thank you for your comment. You are quite right, trade marks can be symbols of identification that are easier to remember and recognise than the full details of the maker, manufacturer or owner.